Health & Science

How your childhood shapes your politics; How cooking made us smart; The volcanic soil of Mars; Why dinosaurs had feathers

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

How your childhood shapes your politics

Your decision to vote for President Obama or Mitt Romney this week may have originated in your childhood. That’s the implication of a long-term study into the voting behavior of 700 people, whose parents were interviewed about how they were raised and how they acted as children. Researchers found that regardless of race, economic status, intelligence, or gender, kids whose parents believed that children “should always obey their parents” were more likely to vote conservative when they reached voting age, while those whose parents believed that “children should be allowed to disagree with their parents” were more likely to become liberals. The study also found that people whose parents described them as having been fearful and cautious at ages 4 and 5 leaned Republican as young adults; those who were active and restless as young children tended to prefer Democratic policies later on. Scientists aren’t sure how our childhood temperaments and experiences lead us “to develop specific ideological positions,” University of Illinois psychologist R. Chris Fraley tells the Toronto Star. But it’s clear, he says, that how we behaved—and were disciplined—as kindergarteners at least partly determines our views on political issues like “abortion, military spending, and the death penalty.”

How cooking made us smart

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Why did the brains of our human ancestors experience a growth spurt some 1.8 million years ago, granting us intelligence that’s superior to that of other primates? Credit “the invention of cooking,” Brazilian neuroscientist Suzana Herculano-Houzel tells The Guardian (U.K.). She and her colleagues found that heating food—which speeds up chewing and digestion, and allows the body to absorb more nutrition per bite—enabled Homo erectus to ingest the calories needed to feed the human brain. Our brain makes up 2 percent of our body mass, or five times the proportion of a gorilla’s brain, and consumes 20 percent of our total energy intake—more than twice the percentage a gorilla’s brain requires. After examining the caloric requirements of a host of primate species, the researchers determined that had our Homo erectus ancestors stuck to a raw-food diet, they would have had to spend more than nine hours per day just ingesting food in order to fuel their larger brains. “Cooking,” Herculano-Houzel says, is the “most obvious answer to the question, ‘What can humans do that no other species does?’”

The volcanic soil of Mars

NASA’s Curiosity rover has completed its first analysis of Martian soil since its stunning landing in August, yielding a surprising conclusion, Space.com reports. The rover bombarded soil at its landing site in Gale Crater with X-rays, which revealed its makeup to be “similar to some weathered basaltic materials that we see on Earth,” such as the volcanic sands of Hawaii, says Indiana University mineralogist David Bish. The sample contained pyroxene and olivine, minerals common in Earth’s mantle, and a type of feldspar found in our planet’s crust—none of which had previously been observed on Mars. The minerals did not appear to be weathered by water, unlike another area Curiosity studied, which indicates that the Red Planet has a complex geological history and probably transitioned from a wet period to a very dry one. Researchers next plan to use another rover tool to search for lighter elements—such as nitrogen, hydrogen, and oxygen—that could have given rise to life.

Why dinosaurs had feathers

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Dinosaurs developed feathers not to facilitate flight, but as a colorful means to attract mates. That’s the conclusion of scientists who closely studied the fossils of one of the earliest feathered dinosaurs ever found. Archaeologists had long been puzzled by the fact that the fossils of feathered dinosaurs unearthed over the past several decades were almost all of beasts far too big to fly. Now, a new analysis of the 75-million-year-old fossil skeletons of an adult and a juvenile Ornithomimus,unearthed in 1995 in Alberta, has established that only the adult—an ostrich-like creature that weighed up to 400 pounds—had the marks of large feathers on its forearms; the juvenile was covered only in a wispy down coat. “This suggests that the wings were used for purposes later in life, like reproductive activities such as display or courtship,” University of Calgary paleontologist Darla Zelenitsky tells NPR.org. Ornithomimus, which evolved some 155 million years ago, is among the earliest feathered dinosaurs yet discovered, so if his feathers served his amorous ambitions, the same is probably true for subsequent dinosaurs.

-

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies end

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies endFeature 1.4 million people have dropped coverage

-

Anthropic: AI triggers the ‘SaaSpocalypse’

Anthropic: AI triggers the ‘SaaSpocalypse’Feature A grim reaper for software services?

-

NIH director Bhattacharya tapped as acting CDC head

NIH director Bhattacharya tapped as acting CDC headSpeed Read Jay Bhattacharya, a critic of the CDC’s Covid-19 response, will now lead the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

-

5 recent breakthroughs in biology

5 recent breakthroughs in biologyIn depth From ancient bacteria, to modern cures, to future research

-

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkiller

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkillerUnder the radar The process could be a solution to plastic pollution

-

Scientists want to regrow human limbs. Salamanders could lead the way.

Scientists want to regrow human limbs. Salamanders could lead the way.Under the radar Humans may already have the genetic mechanism necessary

-

Is the world losing scientific innovation?

Is the world losing scientific innovation?Today's big question New research seems to be less exciting

-

Breakthrough gene-editing treatment saves baby

Breakthrough gene-editing treatment saves babyspeed read KJ Muldoon was healed from a rare genetic condition

-

Humans heal much slower than other mammals

Humans heal much slower than other mammalsSpeed Read Slower healing may have been an evolutionary trade-off when we shed fur for sweat glands

-

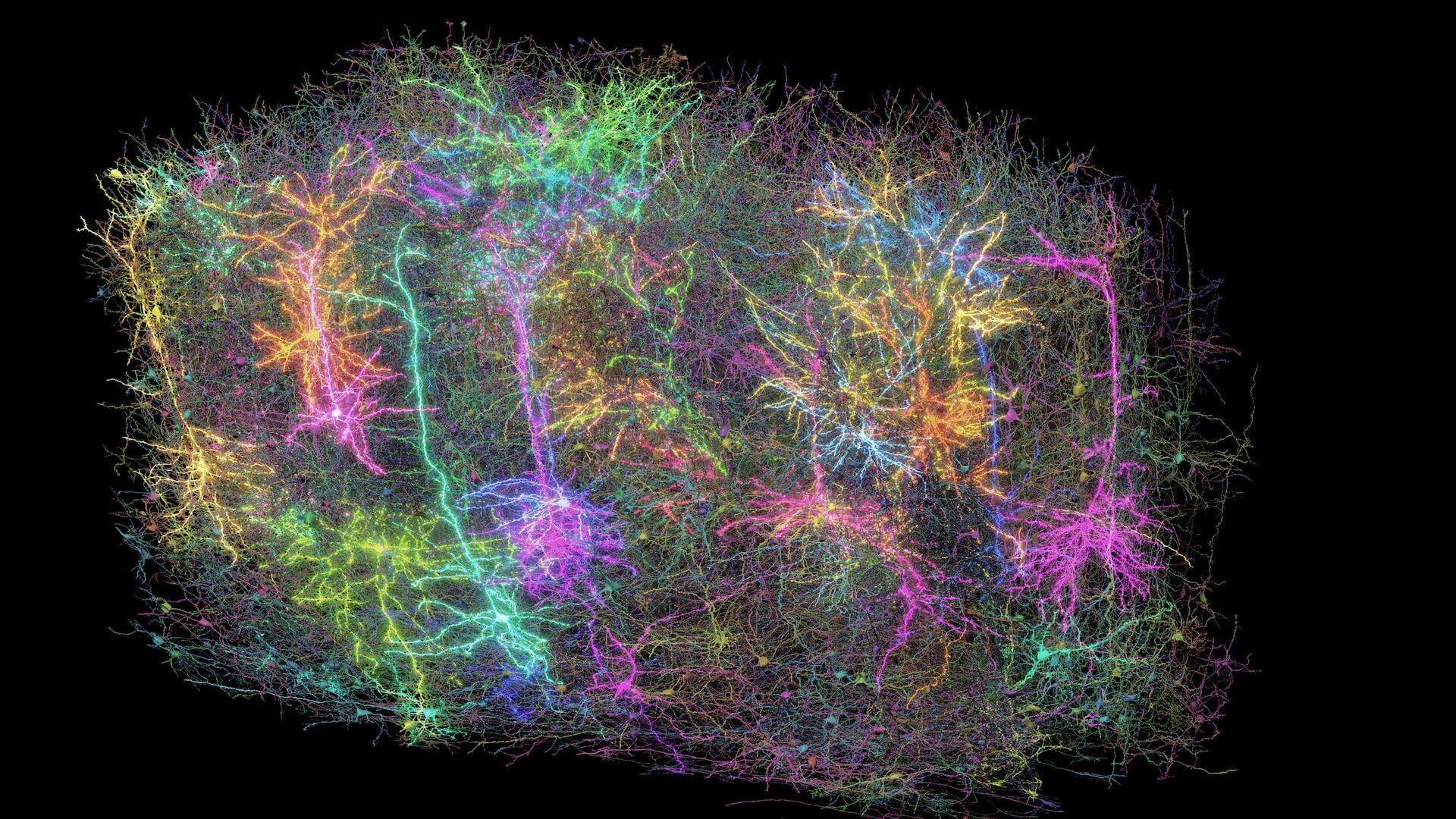

Scientists map miles of wiring in mouse brain

Scientists map miles of wiring in mouse brainSpeed Read Researchers have created the 'largest and most detailed wiring diagram of a mammalian brain to date,' said Nature

-

Scientists genetically revive extinct 'dire wolves'

Scientists genetically revive extinct 'dire wolves'Speed Read A 'de-extinction' company has revived the species made popular by HBO's 'Game of Thrones'