Health & Science

Older fathers and the autism surge; A vanishing Arctic ice cap; Why college kids binge; Fukushima’s mutant butterflies

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Older fathers and the autism surge

The older a man is when he becomes a father, the more likely he is to pass on genetic mutations that can cause autism, schizophrenia, and other disorders in his children, a new study has found. The finding suggests that autism rates are rising in part because men are waiting longer to have children. Researchers analyzed the genetic makeup of 78 Icelandic families in which offspring had been diagnosed as having autism or schizophrenia. They found that those disorders arose primarily from random mutations in the DNA provided by the father’s sperm. Women produce their eggs early in life, so over time, there is no significant increase in mutations. But men constantly produce new sperm, and the process of genetic copying becomes more imprecise as they age. A 20-year-old father was found to contribute an average of 25 new genetic mutations to his child; by the age of 40 that average had risen to 65. Only a fraction of those mutations lead to mental disorders. Still, University of Iceland geneticist Kari Stefansson tells the Los Angeles Times, the trend toward later fatherhood is “very likely to have made meaningful contributions to increased diagnoses of autism in our society.” He attributes 15 to 30 percent of autism cases to genetic mutations from older fathers. Even so, the risk of a man in his 40s fathering a child with genetic disorders remains relatively low at 2 percent.

A vanishing Arctic ice cap

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

New satellite data shows that the Arctic ice cap shrank to its smallest size ever by the end of August, surpassing the previous record-setting ice retreat in 2007. At the current rate, researchers fear, the Arctic Ocean could be completely ice-free during the summer within just a few decades—almost a half-century sooner than climate models predicted only five years ago. “What you’re seeing is more open ocean than you’re seeing ice,” Ted Scambos, a researcher at the National Snow and Ice Data Center, tells Reuters.com. It “just doesn’t look like the Arctic Ocean anymore.” Climate change, scientists say, is warming the Arctic almost twice as quickly as the rest of the globe. Since Arctic ice cools polar regions and influences climate patterns for the rest of the globe, its disappearance will have widespread implications. When ice disappears, the dark surface of the ocean absorbs 90 percent of sunlight, warming the water, quickening further ice melt, and accelerating the rise of global temperatures.

Why college kids binge

College students binge drink not because they love being wasted and hungover, but to raise their social status, a new study shows. Colgate University researchers surveyed students at an unnamed Northeastern liberal arts college and found that those with the highest social status—wealthy, white fraternity brothers—drank far more than the least popular students and reported feeling far more satisfied with their college experience. “Binge drinking then becomes associated with high status and the ‘cool’ students on campus,” study author Carolyn Hsu tells Time.com. As a result, social outcasts try to fit in by pounding down more alcohol. The perceived social benefits of binge drinking were large enough, in fact, that many students did it even though they didn’t enjoy the actual experience of getting smashed. The price for this sort of acceptance is steep: Binge drinking kills more than 1,700 college students per year, and makes students vulnerable to sexual assault and alcoholism—not to mention lousy grades.

Fukushima’s mutant butterflies

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Japanese scientists have discovered disturbing evidence that radiation released during the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster has damaged the genetic makeup of local wildlife. Researchers from the University of the Ryukyus found that 12 percent of pale grass blue butterfly larvae collected in Fukushima in the aftermath of the meltdown developed mutations as adults—including damaged wings, legs, antennae, and eyes. When the researchers bred those butterflies with each other in the lab, 18 percent of their offspring had similar mutations, even though they’d never faced radiation themselves. When those butterflies, in turn, were bred with healthy ones, 34 percent of their offspring showed abnormalities. Meanwhile, more than half of the wild butterflies collected from Fukushima six months after the meltdown had harmful mutations. The findings show that “nature in the Fukushima area has been damaged” by radiation, study author Joji Otaki tells LiveScience.com. Particularly unsettling, says University of South Carolina biologist Timothy Mousseau, is that the mutations appear to accumulate in the gene pool, “leading to larger effects with each generation.” In coming years, researchers warn, genetic deformities and diseases could appear in animals and perhaps even people.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

5 recent breakthroughs in biology

5 recent breakthroughs in biologyIn depth From ancient bacteria, to modern cures, to future research

-

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkiller

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkillerUnder the radar The process could be a solution to plastic pollution

-

Scientists want to regrow human limbs. Salamanders could lead the way.

Scientists want to regrow human limbs. Salamanders could lead the way.Under the radar Humans may already have the genetic mechanism necessary

-

Is the world losing scientific innovation?

Is the world losing scientific innovation?Today's big question New research seems to be less exciting

-

Breakthrough gene-editing treatment saves baby

Breakthrough gene-editing treatment saves babyspeed read KJ Muldoon was healed from a rare genetic condition

-

Humans heal much slower than other mammals

Humans heal much slower than other mammalsSpeed Read Slower healing may have been an evolutionary trade-off when we shed fur for sweat glands

-

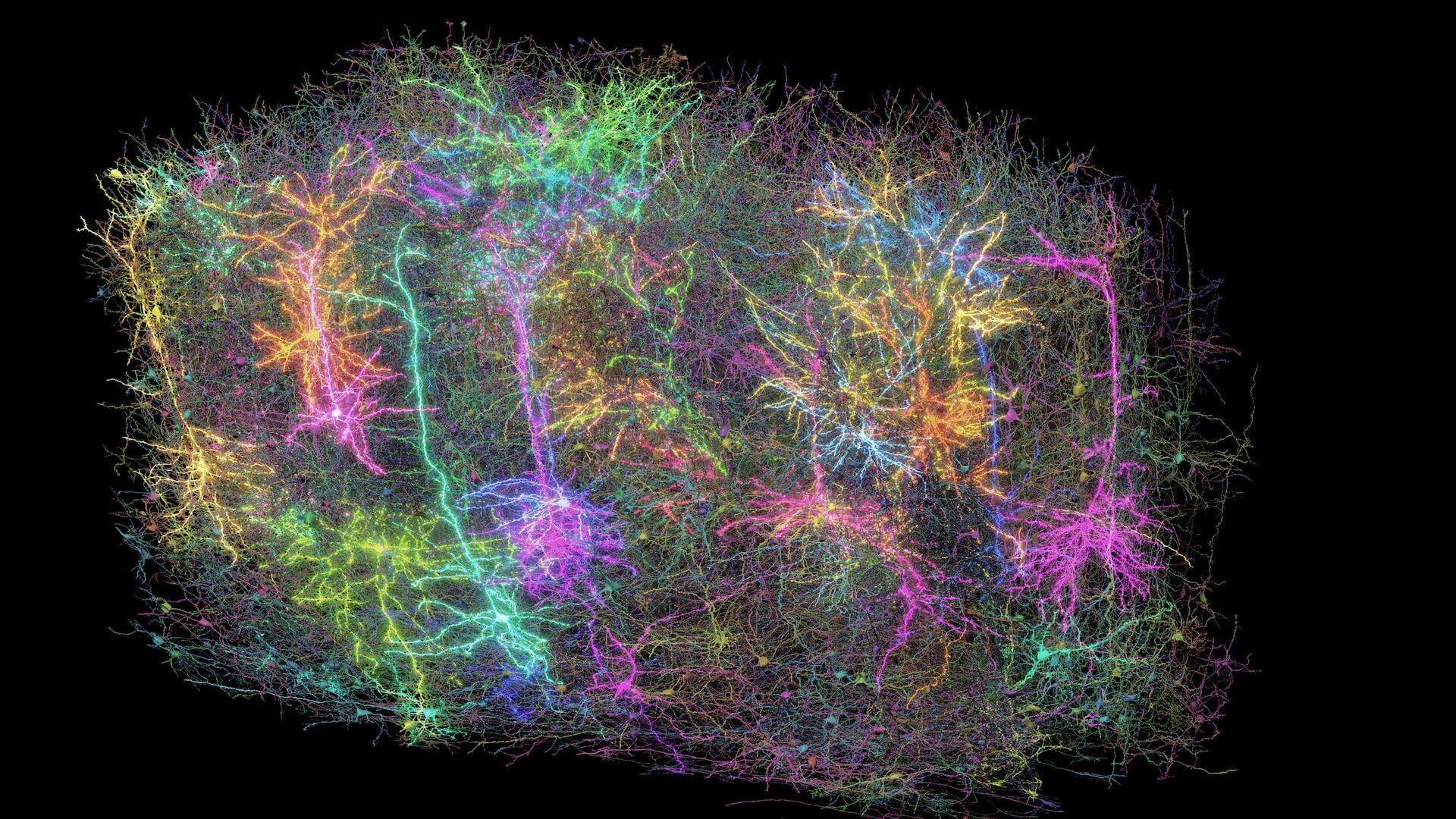

Scientists map miles of wiring in mouse brain

Scientists map miles of wiring in mouse brainSpeed Read Researchers have created the 'largest and most detailed wiring diagram of a mammalian brain to date,' said Nature

-

Scientists genetically revive extinct 'dire wolves'

Scientists genetically revive extinct 'dire wolves'Speed Read A 'de-extinction' company has revived the species made popular by HBO's 'Game of Thrones'