Health & Science

A link between obesity and autism; A mammoth discovery; The benefits of being bilingual; Why homophobes hate

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A link between obesity and autism

Is America’s obesity epidemic causing the mysterious surge in autism? A new study shows that obese pregnant women are 60 percent more likely to give birth to a child with autism than women of a healthy weight—and twice as likely to have a child with some developmental disorder. About a third of American women of reproductive age are now considered obese. Last month, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that one in 88 children has autism or a related disorder, such as Asperger’s syndrome—up from one in 110 several years ago. The study doesn’t prove a causal connection between obesity and autism, but the fetal brain is “susceptible to everything that’s happening in the mother’s body,” study author Irva Hertz-Picciotto, an epidemiologist at the University of California, Davis, tells The Wall Street Journal. Her theory is that overweight mothers tend to have insulin disorders that can increase inflammation in fetal brain tissue, damaging its ability to take in necessary nutrients and oxygen at key developmental stages. Researchers have established a significant genetic component to autism, but the obesity finding is in line with recent studies pointing to other factors, including older parental age and air pollution.

A mammoth discovery

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

A remarkably well preserved baby woolly mammoth found frozen in the Siberian permafrost was partly eaten by humans 10,000 years ago, a new analysis has concluded. The mammoth—unearthed two years ago—had strawberry-blond hair and pink flesh. “Deep, unhealed scratches in the hide and bite marks on the tail” suggest that the 2.5-year-old mammoth was first attacked by lions, University of Michigan paleontologist Daniel Fisher tells Discovery News. Its broken hind leg is evidence that it fell and injured itself while running away. But jagged cuts in its hide indicate that humans quickly arrived on the scene, using primitive tools to finish off the young mammoth and butcher it. They carried away some meat and organs before burying the rest of the carcass, Fisher says, probably “to keep it in reserve for possible later use.” The “extremely rare” specimen, nicknamed Yuka, is the first concrete evidence that humans hunted mammoths during the last ice age, says University of Manitoba physiologist Kevin Campbell. Extracting DNA from the creature “may well lead to important new discoveries,” he says—including the ability to create a living mammoth clone.

The benefits of being bilingual

Speaking two languages can help you stave off dementia. That’s the conclusion of Canadian researchers investigating the effects of bilingualism on both children and older adults. In one recent study, they found that English-speaking children who were also fluent in French, Chinese, or Spanish were better at multitasking, paying attention, and organizing their thoughts than their monolingual peers. In a second study, researchers reviewed the hospital records of elderly patients diagnosed with dementia and discovered that those who were bilingual tended to develop the condition three to four years later than monolingual patients with otherwise similar backgrounds. The findings suggest that mastering two languages can strengthen a person’s “executive functioning,” or ability to control their thinking. Those who “do crossword puzzles and exercise and learn a musical instrument” bolster that ability, too, psychologist Ellen Bialystok of York University tells NPR.org. But, she says, most people spend far more time each day chatting than they do solving puzzles or playing the piano, so bilinguals have “a way to get massive doses of this stimulating activity without doing anything special.”

Why homophobes hate

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

People who lash out at gay people with anger and hate are often reacting to repressed homosexual tendencies of their own. That’s the finding of a new study that suggests that many vocal homophobes “protest too much” precisely because deep down “they are fearing their own impulses,” University of Rochester psychologist Richard Ryan tells LiveScience.com. He and his colleagues asked German and American college students a series of questions to judge their attitudes, and those of their parents, toward homosexuality. Then they tested the subjects’ subconscious attraction to the same sex, in part by asking them to rate the attractiveness of men and women in a series of photos while recording how much time they spent looking at each photo. The researchers found that the students who came from the most rigid, anti-gay homes were the most likely to reveal repressed homosexual attraction. This explains why some religious leaders who frequently denounce homosexuality, such as the Rev. Ted Haggard, are later discovered to be engaging in secret homosexual relations, Ryan said. “These are people who are at war with themselves, and they are turning this internal conflict outward.”

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

5 recent breakthroughs in biology

5 recent breakthroughs in biologyIn depth From ancient bacteria, to modern cures, to future research

-

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkiller

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkillerUnder the radar The process could be a solution to plastic pollution

-

Scientists want to regrow human limbs. Salamanders could lead the way.

Scientists want to regrow human limbs. Salamanders could lead the way.Under the radar Humans may already have the genetic mechanism necessary

-

Is the world losing scientific innovation?

Is the world losing scientific innovation?Today's big question New research seems to be less exciting

-

Breakthrough gene-editing treatment saves baby

Breakthrough gene-editing treatment saves babyspeed read KJ Muldoon was healed from a rare genetic condition

-

Humans heal much slower than other mammals

Humans heal much slower than other mammalsSpeed Read Slower healing may have been an evolutionary trade-off when we shed fur for sweat glands

-

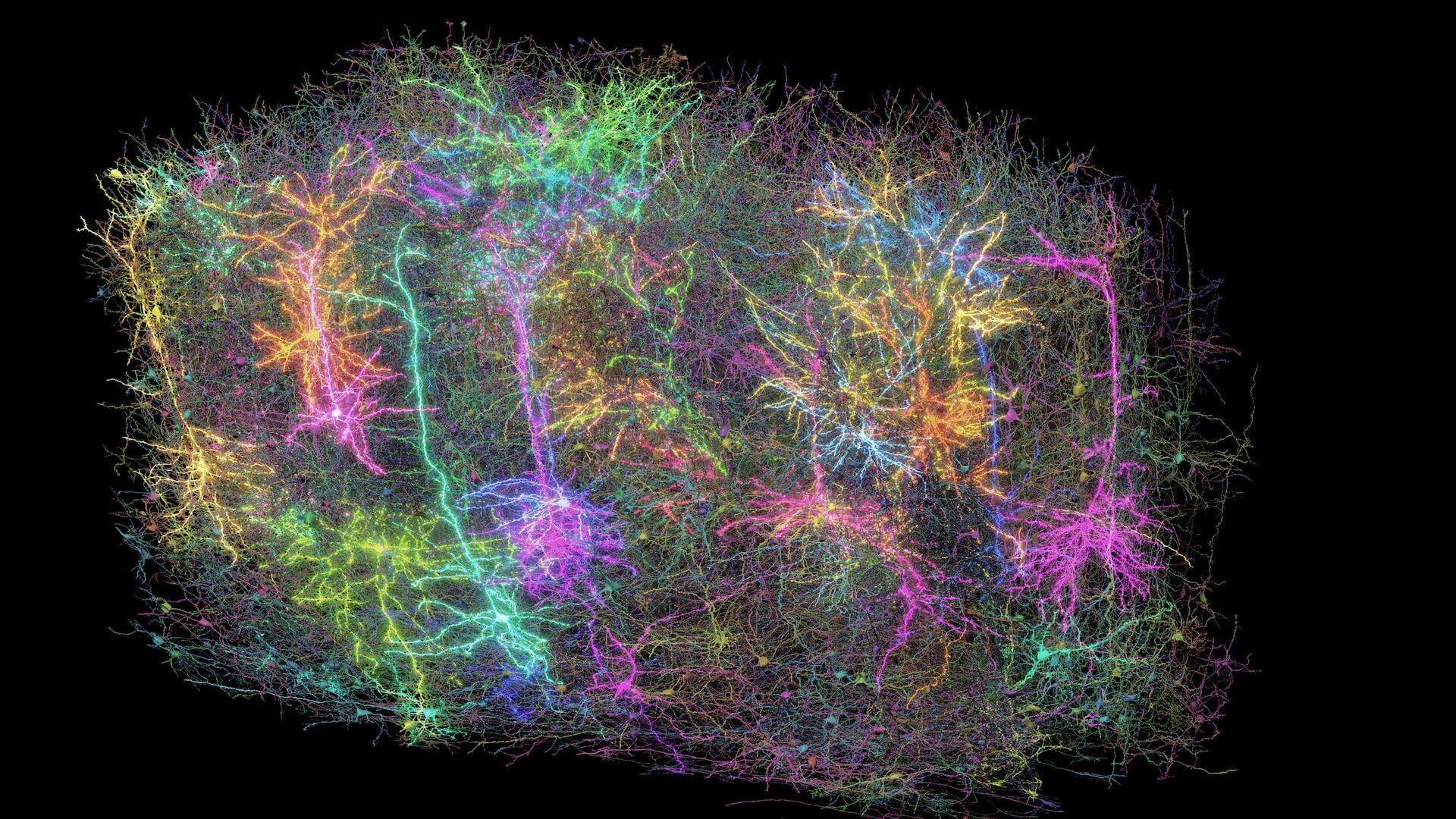

Scientists map miles of wiring in mouse brain

Scientists map miles of wiring in mouse brainSpeed Read Researchers have created the 'largest and most detailed wiring diagram of a mammalian brain to date,' said Nature

-

Scientists genetically revive extinct 'dire wolves'

Scientists genetically revive extinct 'dire wolves'Speed Read A 'de-extinction' company has revived the species made popular by HBO's 'Game of Thrones'