The first postmodern political assassination

In a Turkish assassination, the West sees its frightening future

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

2016 is not finished with us yet.

Compounding regional and global fears of a lurch toward wider war, Mevlut Mert Altintas, an Ankara policeman, assassinated Andrei Karlov, Russia's ambassador to Turkey, in a stunning attack on Monday. With U.S.-Russian tensions already spiking amidst election-hacking allegations, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's regime more authoritarian than ever following this summer's failed coup, and the calamitous consequences of Aleppo and Mosul playing out in real time, this assassination is horrifying and worrisome.

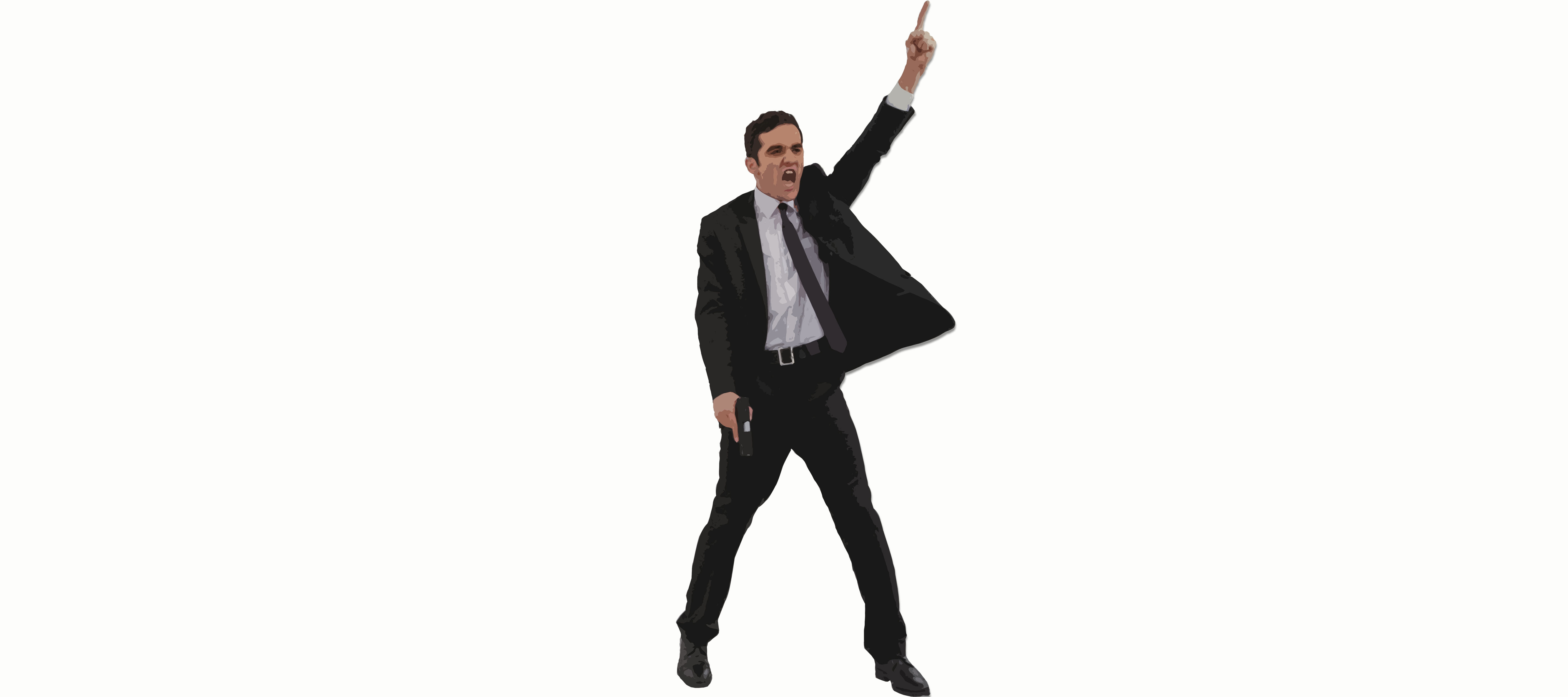

To make matters worse, the manner of Karlov's killing seemed to confirm fears that the world's biggest sources of instability and insecurity are converging ever faster and more powerfully. In a scene as postmodern as anything out of Don DeLillo, J.G. Ballard, or Michel Houellebecq — all caught on well-shot, high-quality video as Karlov was preparing to deliver televised remarks at a photography exhibition — the 22-year-old Altintas looked like an H&M model, complete with skinny tie and black suit, against the sterile, generic white backdrop of the exhibit space. But he spoke the sort of words we are accustomed to hearing from bearded terrorists in grainy or shaky-cam videos, invoking jihad and Syria, and vowing that he wouldn't be taken alive. (Altintas was true to his word. Authorities gunned him down, as you can also see online, after stunned spectators were permitted to leave.)

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The footage — unleashed across social media unedited and uncensored — epitomized everything threatening about the fusion of youth, media, technology, and radicalism. In this startlingly clear view of the first postmodern political assassination, the West saw its future. And it is terrifying.

Officials from Russia and Turkey rushed to impose interpretations of events that stuck closely to established scripts. Ankara's mayor, activating a key narrative of the Erdogan regime, called Altintas a Gulenist — a follower of the exiled cleric and U.S. resident blamed by Erdogan for the recent ruthlessly suppressed coup he has used as a pretext for unprecedented purges and repression. And the Russian Foreign Ministry, through spokeswoman Maria Zakharova, labeled Altintas a terrorist — in keeping with Moscow's insistence that its primary aim in Syria and the broader Mideast is to defeat ISIS and its ilk.

On social media, the competing claims have already become weapons in a war of words over U.S.-Russia relations, Syria's Assad regime, which Russia supports and Turkey opposes, and moral responsibility for the catastrophe in Aleppo, where Moscow and Ankara are working in concert to evacuate what's left of the city's population amid the rebels' final defeat.

However postmodern Karlov's assassination may be, it is locked within a firmly modern context — the calculating machinations of old-fashioned autocrats.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Prone as the internet may be to magnify and manufacture fantasy news, in this case, the truth is plain to see. Karlov's assassination is not only a shocking demonstration of the world's fears of the future. It's also another crack in the foundation of the geopolitical present, eerily echoing cataclysms of the past. The metaphor some analysts and observers immediately reached for was the assassination more than 100 years ago of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, a killing that sparked the first World War. It's a strained comparison, but one that underscores today's prevailing sense that the existing global order is on borrowed time, one tap away from toppling. Ideological expectations are shaking and blurring. While President Obama has come under attack from the left as well as the right for his restrained approach to Russia, President-elect Trump is the focus of enmity from both sides for taking a more friendly tack. (Trump is even on record supporting Gulen's extradition to Turkey.) Yet very few Americans are thirsting for deeper U.S. involvement in the Syria debacle, or a cascade toward outright war with Russia. Ignorance, reflexive hatred, and conspiratorial superstitions thrive in the West today. But so does a growing, cross-partisan demand for a more peaceful, predictable world.

And that, in a nutshell, is why Western liberalism finds itself increasingly under attack both abroad and at home. Elites have lost too much trust in their ideals to lead their nations to full-dress war with autocracies. In the U.S., illiberal radicals and reactionaries cry out for a decisive break with American globalism, interventionism, and capitalism. In Europe, where both types of the anti-liberal fringe actually enjoy a long (if bloody) history of viability and control, the focus is on punishing globalism less for its strengths than its weaknesses, epitomized by the EU's inability to ensure economic growth, cultural coherence, political pride, or basic security. Dark as illiberal life in Russia, Turkey, or China may be, the message many in the West's democracies will hear from Altintas is this: In a more violent world, you, too, will learn to abandon all hope.

James Poulos is a contributing editor at National Affairs and the author of The Art of Being Free, out January 17 from St. Martin's Press. He has written on freedom and the politics of the future for publications ranging from The Federalist to Foreign Policy and from Good to Vice. He fronts the band Night Years in Los Angeles, where he lives with his son.