France's populist uprising

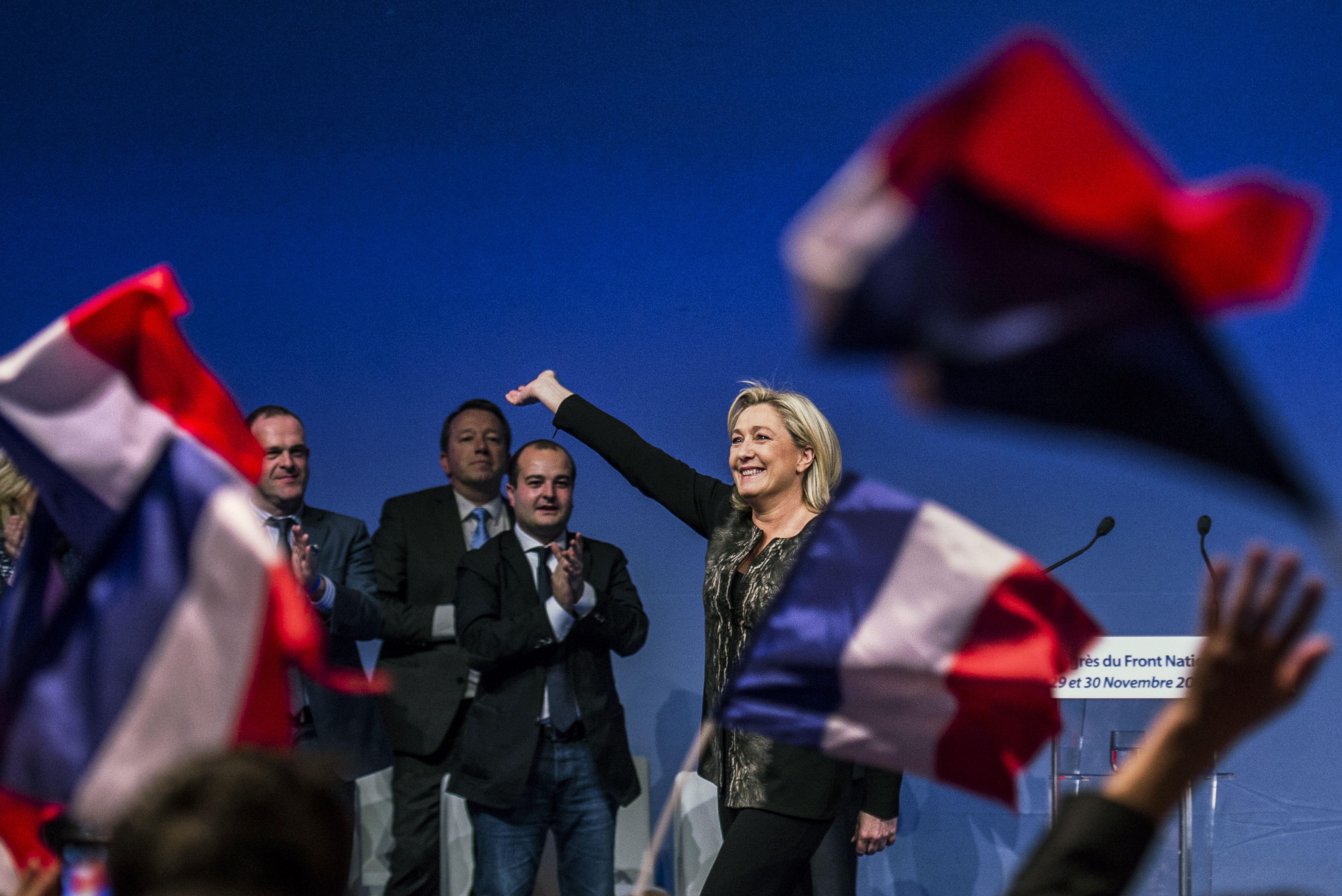

Far-right nationalist Marine Le Pen has a chance to win the country's presidential election. What's propelling her rise?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Far-right nationalist Marine Le Pen has a chance to win the country's presidential election. What's propelling her rise? Here's everything you need to know:

What is at stake in the election?

France is having a contentious argument about what it means to be French. An influx of immigrants from former colonies such as Algeria and Morocco — and a much higher birth rate among those groups — is rapidly transforming the country's demographics. France is about 8 percent Muslim overall, but some 25 percent of French high school students are Muslim. That's caused alarm in a nation repeatedly struck by radical Islamist terrorism; so has Muslim religiosity in a nation with a rigorously secular culture. At the same time, the inflexible French economic system, with its strong welfare state and rigid labor laws, has struggled to adapt to globalization. Unemployment is stuck at 10 percent, and is 26 percent among those under 30. The split between the educated elite of Paris and the left-behinds of the small towns has deepened into what author Christophe Guilluy calls a "total cultural fracture." France, he says, "has become an American society just like all the rest, with its identity-based tensions and paranoias." In the first round of France's presidential election on April 23, the same forces that pushed Britons to choose Brexit and Americans to choose Donald Trump could produce a victory for Marie Le Pen's National Front — and a political earthquake for all of Europe.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Who's running?

There are 11 candidates in the first round, but only four stand a chance of making it to the May runoff of the top two vote-getters. Center-right Republican candidate François Fillon, a social conservative who wants to reform labor laws and cut spending, is polling last of the four, because of accusations that he paid his wife and children for phantom government jobs. Upstart far-left populist Jean-Luc Mélenchon, polling third at about 19 percent, wants to withdraw from NATO and free-trade pacts, boost worker benefits and reduce the work week, and impose a 100 percent tax rate on incomes above $430,000. Centrist Emmanuel Macron, a dashing young banker and economics minister who promises to save the middle class by investing in vocational training, is at 24 percent. But the focus of the election is on the nationalist Le Pen, also polling at 24 percent. She wants France to turn its back on Europe and immigration, and return to uniquely French customs and traditions.

What would Le Pen do?

Le Pen sees Frenchness as under attack from three forces: Islam, the EU, and globalization. She would defend it by halting immigration from former colonies and amending the constitution to establish the primacy of Christianity. To throw off the tyranny of EU regulations made in Brussels, Le Pen promises a referendum on continued membership, raising the possibility of a "Frexit" that could utterly destroy the union. She also wants to take France out of the euro, the shared European currency, and bring back the franc. Her policy of "economic patriotism" would punish firms that relocated factories abroad and would protect French farmers with tariffs on imported food.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Who are her supporters?

National Front supporters are largely working-class — small-town residents who feel that globalization has left them behind and replaced traditional local shops with big-box stores. Many of them are deeply mistrustful of Islam and horrified that France's historic but half-empty churches are falling into disrepair while new mosques spring up. Le Pen has plenty of youth support from a burgeoning "alt-right" movement called the Identitarians, who say France is being "reverse-colonized" by its former colonies in Africa. Le Pen also has the support of Russia.

How is Russia involved?

French banks refused to lend the National Front money, so Le Pen turned to Russia for funds in 2014. Nearly $10 million came from a bank with ties to the Kremlin, and Le Pen repaid that with nearly total support for the policies of President Vladimir Putin. She said Moscow had the right to take Crimea from Ukraine, and has vowed if elected to lift EU sanctions against Russia. Macron, meanwhile, has alleged that cyberattacks against his campaign and a proliferation of pro–Le Pen "fake news" stories on social media are being orchestrated by Russia, a charge Moscow denies. What's clear, though, is that Russia supports the far right all over Europe. "He knows the extreme right divides us," says European Commission Vice President Frans Timmermans, "and a divided Europe means that Putin is the boss."

Who will win?

The last time the National Front got into the runoff, under Le Pen's father Jean-Marie in 2002, the entire French establishment, left and right, closed ranks against him, and he took less than 18 percent of the vote. But the mainstream parties that have taken turns ruling France for decades are out of favor, and the establishment is largely dead. If Macron makes it to the runoff, he is favored to win — but Le Pen could upset him if Mélenchon's supporters, who regard Macron as an ultracapitalist, stay home in disgust. And if Mélenchon makes the second round with Le Pen, the choice will be between an anti-EU, pro-Moscow candidate of the ultraleft or an anti-EU, pro-Moscow candidate of the ultraright. Almost anything could happen: About a week before election day, 40 percent of voters declared themselves undecided.

A legacy of anti-Semitism

The National Front was founded by Le Pen's father, convicted Holocaust denier Jean-Marie Le Pen, and for years it was seen as a racist fringe movement. Marine changed that, kicking her father out of the party leadership for his anti-Semitic comments and carefully avoiding any overtly supremacist rhetoric. But hints of anti-Semitism are creeping back into her campaign. Many of Le Pen's supporters have taken to denouncing her rival Macron by chanting "Rothschild!" — an anti-Semitic dog whistle referencing the bank where he worked. Last week, Le Pen declared that the French state was not responsible for World War II–era crimes against French Jews and bore no national guilt for shipping thousands off to Nazi gas chambers. Her former adviser Aymeric Chauprade says Le Pen's top two aides are "anti-Semites, nostalgic for the Third Reich, violently anticapitalist, with a hatred for democracy."