The dangerous seduction of simplicity

It allows Trump to distract and thrive while we ignore broader injustices and humanitarian crises

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It's the simple stories that stick with us.

This is a crucial lesson of the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi at the Saudi consulate at Istanbul. The Khashoggi story is simple. It has a clear main character and can be told in one sentence: A brave dissident journalist was brutally killed by the government he challenged.

Compare the simplicity of the Khashoggi story to the complex and grotesque horrors in Yemen. For three years Saudi Arabia has, with American help, inflicted obscene misery on the people of Yemen. Children are starving to death and being blown up in their school buses with U.S.-made bombs. They face the world's most acute humanitarian crisis, and they are criminally ignored.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Pictures help, but only if we can bear to look. We don't know the names of the Yemeni civilians dying daily of violence, starvation, and preventable disease. We haven't seen the faces of the dozens of children killed on that bus — and even if we had, we wouldn't remember them all.

For most people, one man whose gruesome death we can envision has more political power than 40 nameless kids and their nameless bereaved families. The simple story of a single murder does more than a litany of war crimes perpetrated against an entire nation.

We do not want this to be true. We want to consider ourselves more nuanced. We want to be smarter, more empathetic, possessed of greater intellectual depth. We want to think we're all about identifying structural problems and analyzing large-scale patterns of dysfunction. But usually, we're not.

This dynamic is a plague on criminal justice reform efforts. Statistics about how many people are fatally shot by police each year (802 for 2018, as of this writing) or racial disparities in the justice system will not, for most people (and especially most white people), kindle a fire for change. But let a police officer kill a single person in a newsworthy way — Eric Garner, mercilessly choked for selling tax-free cigarettes, or Botham Jean, shot in his own apartment — and we'll take to the streets.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Thousands killed by a system that demonstrates vicious habits of discrimination, perverse incentives, and secrecy? Eh. One killed? Time to march.

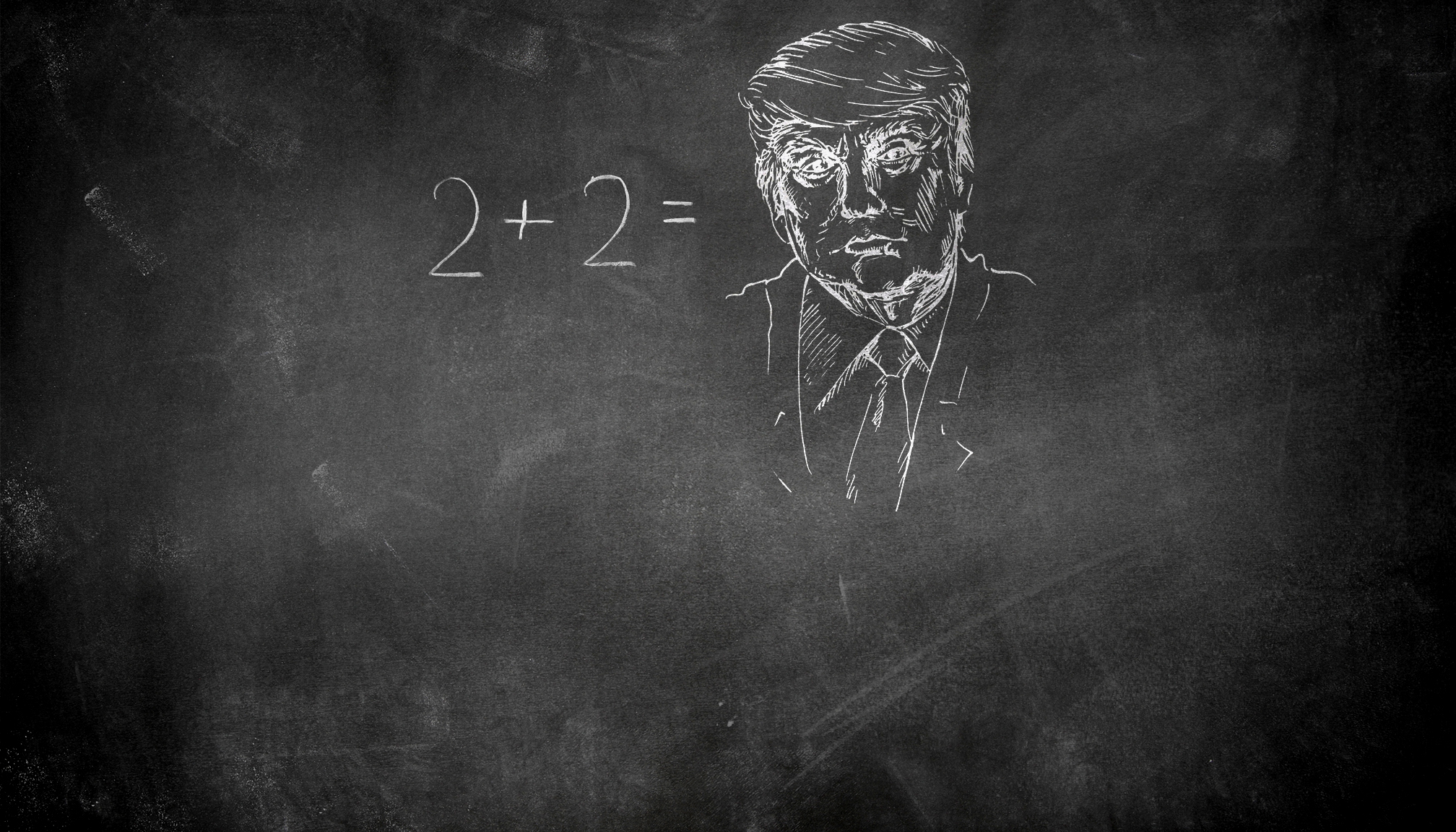

Or consider President Trump, who is a master of making himself the sole main character in a simple story. This technique is essential to his success. "I have joined the political arena so that the powerful can no longer beat up on people that cannot defend themselves," he said at the Republican National Convention in 2016. "Nobody knows the system better than me, which is why I alone can fix it." Like it or hate it, believe it or deny it, this is a simple story, easy to envision and easy to remember. We're all aware of Trump's posturing as the lonely hero riding in to drain the swamp.

Simplicity has also been key in opposition to Trump. I would like to see Democrats retake Congress this election in an almost certainly vain hope that they would impose real and permanent strictures on the power of the presidency. But congressional Democrats en masse are not an effective political foe for the president. There are too many of them.

On the one side, there's a single character — Trump. On the other side, there's ... several hundred people you don't know? It's like watching a superhero fight off a horde of faceless criminal henchmen: Nothing really matters until the Big Bad appears. In a fight of one vs. many, our interest will always tend to be with the one.

Thus some of the most durable challenges to Trump have revolved around a single person. Think Special Counsel Robert Mueller, adult film star Stormy Daniels, or Christine Blasey Ford, who accused Trump's Supreme Court nominee, Brett Kavanaugh, of sexual assault. They've displayed a certain staying power in no small part because of the simplicity of the stories they represent. (Ford's case was arguably weakened when other accusers came forward, both because they were less credible and because they muddled the narrative.)

By contrast, many of the results of Mueller's investigation have generated relatively little interest, and understandably so. The stuff with Paul Manafort, George Papadopoulos, or Roger Stone — who can keep track of it all? These are side characters, and there are so many of them!

I say that sincerely, for as much as I believe more disciplined, complex thinking habits are necessary, I also recognize most people have neither the time nor inclination to follow all this. Even I don't always want to follow it, and it's literally my job. As I've argued previously, it is right, normal, and reasonable for most people not to think about politics most of the time.

Still, when we are thinking about politics, how we do it matters. It is dangerous to allow ourselves to be wooed by simplicity and bored by complexity, because the world is not simple. Yemeni children were dying because of the U.S. and Saudi war well before Jamal Khashoggi was murdered, and they continue to die after. If we are so easily seduced by a simple story, the details we ignore may be monstrous.

Bonnie Kristian was a deputy editor and acting editor-in-chief of TheWeek.com. She is a columnist at Christianity Today and author of Untrustworthy: The Knowledge Crisis Breaking Our Brains, Polluting Our Politics, and Corrupting Christian Community (forthcoming 2022) and A Flexible Faith: Rethinking What It Means to Follow Jesus Today (2018). Her writing has also appeared at Time Magazine, CNN, USA Today, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, and The American Conservative, among other outlets.