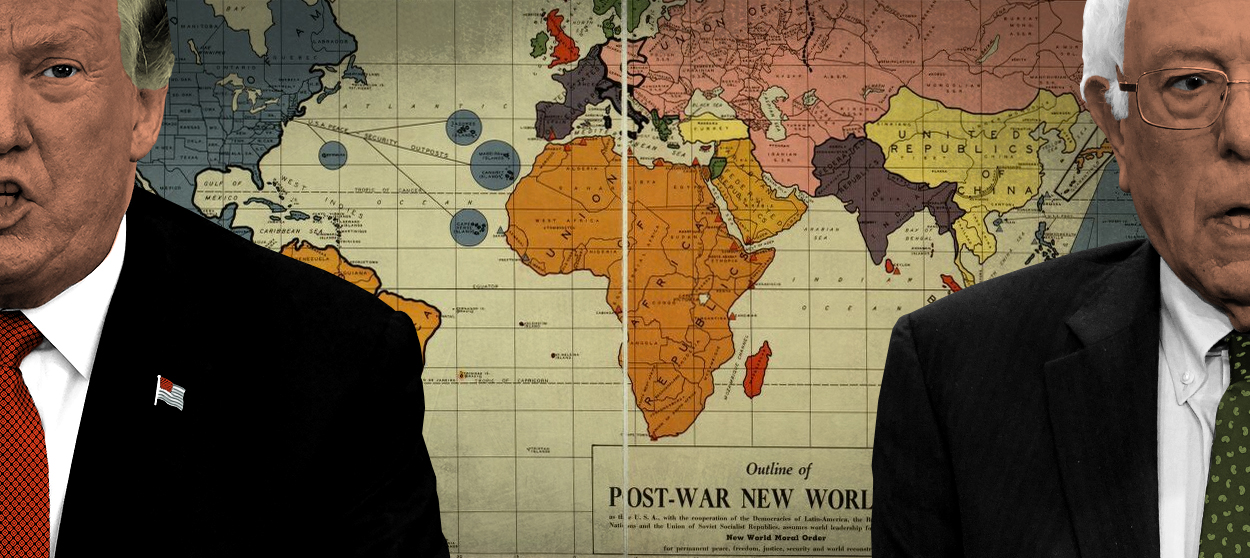

America's dangerous inconstancy

No one knows which America will show up in 2 years. That's a problem.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Partisan polarization is bad. But it may be far worse — and far more damaging to the United States — than we commonly recognize.

Slight variations in policy priorities from one presidency to another are perfectly normal and expected. When a Republican holds the White House and a congressional majority, for example, we expect taxes to go down a bit, foreign policy to be somewhat more combative, and environmental concerns to be de-emphasized relative to what one would expect from a Democratic president and Congress. Such modest shifts are the natural result of democratic elections and the alternation of power between parties.

But over the past couple of administrations we've begun to see something different: much more dramatic swings and shifts from one presidency to another. The United States has started to act like a psychiatric patient with multiple-personality disorder. That's bad for America at home and even worse for our standing abroad. And it's likely to get even worse over the coming years.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Take the recent announcement from the campaign of Democratic front-runner Bernie Sanders that, as president, he would "rejoin the JCPOA and would also be prepared to talk to Iran on a range of other issues." Even if you agree with this position on the substance, as I do, the promise is troubling. It means that in the space of around six years, the U.S. would have reached and implemented the multilateral Iran nuclear deal (under President Obama), walked away from and quite possibly scuttled the deal altogether (under President Trump), and then sought to reinstitute and join it all over again (under President Sanders).

That is simply not the behavior of a country hoping to exercise a leadership role on the world stage. It's the behavior of a country so divided about its geopolitical goals, strategies, priorities, and tactics that it lurches incoherently between positions from one president to another, leaving the nations of the world, including our allies, our rivals, and our adversaries, unable to trust or rely on us, or even anticipate our actions, for more than four years at a time.

And it goes far beyond the Iran Deal.

Responding productively to climate change is the greatest collective action problem in human history. Despite the enormous challenges involved, the nations of the world affirmed the Paris Agreement on greenhouse gas emissions in 2015. The goals were modest. The enforcement mechanism nonexistent. It was merely a statement of intentions — a feeble but absolutely essential move in the right direction. And the United States, under Obama, went along with it. Yet in June 2017, Trump signaled his intention to withdraw from the agreement, making the U.S. a global outlier and opening a massive opportunity for other countries to deviate from their own goals for cutting emissions while still appearing to do a better job of compliance than the world's second biggest emitter of greenhouse gasses.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

And of course, if the Democrats come to power in 2020, they will swiftly reverse course once again.

The same dynamic can be seen in foreign policy more broadly.

George H. W. Bush and Bill Clinton were multilateralists, forming large international coalitions and working through the mechanisms of the United Nations and NATO to keep order and uphold international law around the globe. With the Iraq War of 2003, George W. Bush broke sharply from this approach, declaring the U.S. entitled to depose the government of Saddam Hussein in order to implement the administration's construal of U.N. resolutions over the strenuous objections of the U.N. Security Council and most of the nations of the world. That was unilateralism on steroids.

Bush was then followed by Obama, who reverted to the Clintonian approach. He called it "leading from behind," which meant trying to build international consensus and working in concert with other nations to solve common problems wherever possible. No wonder our allies rejoiced at this reversal of the Bush years. At least until they despaired at the reversal of the reversal under Trump, who has in some ways gone even further than Bush in thumbing his nose at much of the world, very much including our closest allies.

Most of the Democrats running for president now would revert once again to multilateralism and internationalism if they took control of American foreign policy. As with the Iran Deal and Paris Agreement, one can consider this worthwhile on substance while also recognizing that the schizophrenic shifting from one approach to the other and then back again does enormous damage to our ability to inspire respect or deference on the part of the rest of the world. Instead, we end up looking confused and incontinent.

The vacillation has even begun to extend to domestic policy, risking a whole different set of negative consequences.

Reagan cut income taxes sharply. Clinton raised them modestly. Bush cut them back and extended them in other areas. Obama raised them slightly again. Throughout this period, the changes from one administration to another were relatively minor. But then Trump and the Republican Congress passed an enormous corporate tax cut, dropping the rate of tax paid by businesses from 35 percent to 21 percent, its lowest rate since 1939.

How likely is it that a Democrat elected in 2020 will keep the corporate rate at 21 percent? Not very. How high is the rate likely to go? It's impossible to say — though several of the current candidates have expressed a desire to raise income taxes on high earners quite sharply. It makes sense to assume that a new president and Congress that reverted to income tax rates not seen since the 1970s would be disinclined to leave Trump's corporate tax cut in place.

Pushing another step into the future, how likely is it that Republicans will defer to a major Democratic tax hike the next time they take control? Not very.

Experts can debate whether drastically raising or lowering tax rates (and adding or slashing government programs and regulations) will have good or bad consequences — for economic growth and inequality, for the safety and well-being of citizens, for the federal deficit and debt. But inconstancy is an entirely separate issue and threat to the good of the nation. We may soon confront a situation in which businesses and individuals find it impossible to plan reliably for the future — because they can have no idea how much tax they will have to pay, or how many and what types of regulations they will need to obey, from one election to the next.

This would be an entirely self-inflicted wound — one growing out of our incapacity to reach anything approaching a consensus about our problems and how to address them. Every time one party hands off power to the other, it's as if an entirely different country with a wholly distinct outlook takes charge, yanking the nation in one of two polar opposite directions. It's a dangerous situation, and we have no idea how to address it.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.