Democracy isn't dying. Liberalism is.

What the expanding empire of anti-liberalism means for the future

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

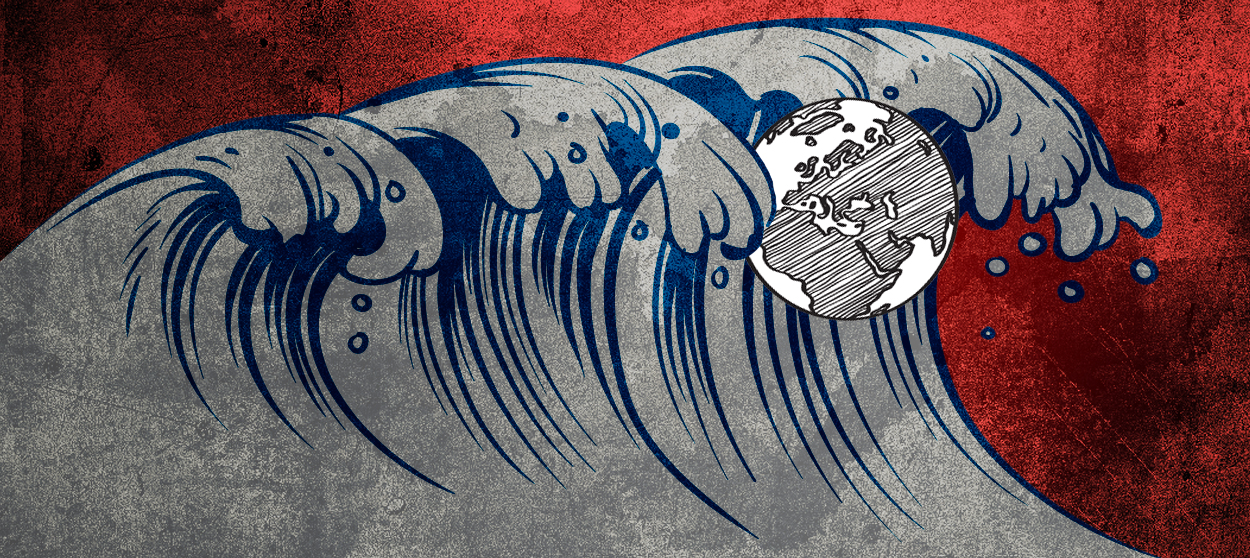

Three years after the twin shocks of President Trump's triumph in the Republican primaries and the narrow win for "Leave" in the Brexit referendum, the evidence has never been stronger that the world has entered an era of anti-liberalism.

Later this week, voters across Europe go to the polls to vote in EU parliamentary elections that could deliver a quarter or more of the seats to the continent's right-wing populists and nationalists. Meanwhile, exit polls in India suggest that Narendra Modi's Hindu nationalist party will win re-election when results are announced on May 23. This follows the surprise victory in Australia of Scott Morrison's conservative coalition, which leaned heavily on populist themes.

These events follow on the heels of many others. Brazil, Colombia, Italy, Hungary, Poland, Austria, Turkey, Russia, Israel, and Japan are all led by right-wing nationalists or populists, or their governing coalitions include parties firmly in that camp. In many other countries, such parties have been founded and won legislative seats. There is no sign yet that the rising tide has crested, or how high it may go.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But what does the shift amount to? Is it a temporary anomaly that can easily be reversed, as Democratic presidential frontrunner Joe Biden likes to imply? Or is it, as many others warn ominously, a sign that democracy itself is under siege?

Both options are wrong. The trend is far too widespread for it to be the result of a fluke that can be quickly and easily reversed. That doesn't mean that the insurgents won't suffer defeats; Biden or some other Democrat may well beat Trump in 2020. But it does mean that the political challenge posed by Trump and the other populists and nationalists is likely to persist for some time to come.

As for the question that The New York Review of Books has plastered across the cover of its most recent issue — "Is democracy dying?" — the answer, quite clearly, is no: Democracy is not in jeopardy. Liberalism is.

It is imperative that we learn to recognize the difference and uphold the distinction. Democracy is nothing more or less than political rule by the people. In ancient Athens, this meant that political offices were allocated by lot: anyone who was a citizen might be called upon to serve. In modern democracies, political offices are won through electoral contests, with the majority or plurality winner of the vote gaining power and serving as a representative of the people.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Liberalism, by contrast, is a modification of government meant to produce balance, fairness, and wisdom. It includes the protection of individual freedoms (rights), an independent judiciary, a free press, and the rule of law, including professional civil servants and bureaucrats who are guided by expertise and a sense of public spiritedness. When these liberal norms and institutions, which aim to regularize and restrain the exercise of government power, are combined with democratic elections, the country is called a liberal democracy. But liberalism can be applied to other forms of government as well.

Whether liberalism is combined with democracy, monarchy, or another form of government, it adds an element of elevation, since it makes distinctions between acceptable and unacceptable uses of government power, good and bad applications of the law, and worthwhile and foolish policy goals. These ongoing acts of ranking and judging place liberalism in tension with contrary political impulses. In a liberal monarchy, the norms and institutions of the liberal state will come into conflict with the will of the king or queen. In a liberal democracy, tensions are more likely to arise between the liberal state and the will of the people, expressed through both elections and public opinion (with the latter measured by opinion polls).

Over the past several decades, this classical understanding of liberalism has become more complicated and muddled, as the center-left and center-right parties that have governed so many of the world's democracies have associated their own constellation of contingent policy preferences with the liberal order itself. To support liberal democratic government as such has meant favoring policies of economic and cultural globalization, including the relatively free movement of people, goods, services, and capital around the globe, along with the practical consequences of those policies, including high rates of immigration, economic growth in cosmopolitan cities with high levels of education, and economic decline in lower-density and rural regions.

The result has been that as political movements have risen up to oppose these policies and their consequences, these movements have not just targeted the politicians and parties that championed them, but "liberalism" itself. And they have done so in the name of democracy.

Such populist appeals are not wholly disingenuous. This can be especially hard to see in the United States, where the Constitution's myriad counter-majoritarian features make it possible for a candidate and party to win the presidency and control of Congress while losing the popular vote. In that context, a populist-nationalist upsurge can take — and in 2016, did take — an anti-democratic form.

But in many other countries, the populists are actually popular. Brexit was approved by a majority. Jair Bolsonaro won the presidency of Brazil with 55 percent of the vote. The populist-nationalist coalition that governs Italy won a solid majority at the polls. The party of the most explicitly and aggressively anti-liberal populist in the world — Viktor Orbán — won Hungary's 2018 election with slightly less than 50 percent, but the runner-up was the even further right-wing Jobbik party with an additional 19 percent.

Across the world, democracy is delivering anti-liberal results. Liberals should be honest about what this means — among other things that they are failing to persuade sufficient numbers of voters to entrust them with power, and that this failure has begun to discredit the very norms and institutions that make our democracies liberal in the broader and deeper sense. The result is likely to be a spike in corruption and a decline in freedom for everyone who isn't owed a favor by the ruling party.

How liberals might do a better job of persuading increasingly hostile voters to give them continued, or a renewed, chance at power is anyone's guess. What's not mysterious is how counter-productive it is when liberals respond to popular opposition by lashing out in condescension at the those who withhold their support. Whether such condescension takes the form of an epithet ("deplorables") or an insinuation that voters are too stupid to recognize the wisdom of casting ballots for politicians who promise to enact liberal policies, it wounds pride and triggers a sense of dishonor among voters that can ensure a deepening of hostility to liberalism.

Liberalism and democracy have gone together for a long time. But there's no guarantee the pairing will last — or that they can easily be brought back into alignment once the ties between them have been severed.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.