Republicans are becoming more like Democrats. So why are Democrats so upset?

Liberals should be cheered by the new economic populism on the right

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

What kind of political opposition would progressives prefer to face?

As partisans, they'd probably opt for the right to adopt the most irresponsible and extreme position possible — because then they (the left) would be more likely to prevail at the ballot box. But would that really be best for the country? Of course not. The country needs (at least) two viable parties attempting to responsibly address the nation's problems. Which is why all public-spirited observers should be modestly encouraged by the ideological changes taking place right before our eyes within the Republican Party.

The most striking recent sign of these changes is a keynote delivered last week by Sen. Josh Hawley (R-Mo.) at the National Conservatism conference in Washington — though you wouldn't know it from most of the commentary about the remarks. The speech is a critique of what the 39-year-old Hawley, who was elected just eight months ago, calls the "cosmopolitan consensus" that "reflects the interests … of a powerful upper class." This consensus prevails among people who "run businesses" or "oversee universities" and who "subscribe to a set of values held by similar elites in other places: [values] like the importance of global integration and the danger of national loyalties; the priority of social change over tradition, career over community, and achievement and merit and progress."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Because Hawley goes on to illustrate this cosmopolitan consensus by quoting four academics, three of whom are Jewish, a flurry of critics have insisted the speech amounts to an anti-Semitic dog whistle, or perhaps that it's simply written in ignorance of the history of anti-Jewish polemics, in the Nazi period and beyond, taking the form of an attack on "rootless cosmopolitanism."

In a debate about rhetorical intent and unstated implications, there can be no certainty. But this reading of the speech strikes me as unpersuasive and unfair. Hawley doesn't identify as Jews the academics he quotes in passing, and it should be possible to raise objections to the trends Hawley highlights without automatically triggering suspicions he's impugning an ethnic and religious minority. Call it cosmopolitanism, globalism, or internationalism: The phenomenon is real — as progressives recognize full well when they label it "neoliberalism."

The real subject of Hawley's talk is class. The international "cosmopolitan class" is "an aristocracy" that he contrasts repeatedly with "the great American middle." This might sound like the typical Republican trope of valorizing "middle America" and contrasting it with decadent elites on the coasts — and it is that to some extent. But it's also a defense of the economic middle class, members of which have been left "with flat wages, with lost jobs, with declining investment and declining opportunity" while "multinational corporations … move jobs and assets overseas to chase the cheapest wages and pay the lowest taxes."

If Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren delivered those lines, no one would have thought twice. But coming from a Republican, it signals a remarkable — and heartening — shift of assumptions and priorities in a small-r republican direction.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Since Reagan, the Republican Party has been ideologically committed to advancing the interests of big business — even as, post-2008, public opinion across the spectrum has shifted in a more populist direction. One reason Trump gained traction in 2016 was that he seemed eager to prioritize the interests of working people, with his defense of entitlements and talk of providing health-care coverage for all, along with his promises to negotiate better trade deals. That turned out to be nonsense, as the clueless, floundering new president ceded control of the administration's policy agenda to Paul Ryan, who first tried to gut people's health insurance and then, when that failed, opted to pass a massive corporate tax cut. Once again, plutocrats were calling the shots — and they continue to do so with the administration's current push to get the Affordable Care Act overturned in the courts.

By contrast, Hawley's speech points to a post-Trump future in which the economic realignment Trump seemed poised to undertake actually gets going. It is fueled not by anti-Semitism or Trumpian racism and xenophobia but by a series of arguments grounded in the republican tradition going back to Aristotle. This tradition emphasizes the importance of fostering a strong, prosperous, independent, public-spirited middle class — and the danger of allowing a corrupt, oligarchic elite to grab too much political power.

Versions of this argument have been made at many times throughout history: on the "country" side of the court v. country debate during the civic tumult of 17th century England; in the writings of Thomas Jefferson and the American anti-Federalists at the time of the founding; in Andrew Jackson's fiery statements denouncing elite corruption during the so-called "bank war" of the 1830s; in the platform of the original Populists (the People's Party) at the end of the 19th century; in the neoconservative critique of the "adversary culture" of intellectuals during the 1970s; in the late writings of social critic Christopher Lasch. Hawley's speech — with its insistence that "a republican nation requires a republican economy," and its appeals to a form of citizenship that "requires independence" and the "power to participate in your community, to provide for your family, to make your own decisions" — needs to be seen as growing out of this venerable tradition of republican thinking.

Some have claimed, instead, that Hawley is expressing the paleoconservative and ultimately racist and anti-Semitic outlook of Patrick Buchanan and Samuel T. Francis. The influence of those ideas — among the bleakest and most sinister expressions of the republican tradition — can certainly be detected in Trump's outlook. But is it really present in Hawley's remarks and early efforts at policymaking? If so, it's there in purely implicit, carefully veiled form.

More significant, I think, is what's right there on the surface — in, for instance, Hawley's strong endorsement of Chris Arnade's important new book, Dignity: Seeking Respect in Back Row America. The book is a powerful, wrenching look — in both words and photographs — of the struggles and suffering of Americans who live economically and spiritually far removed from the elites who run the country and its leading enterprises and institutions. Unlike the million-and-one journalistic profiles of Trump voters that focus only on rural whites, Arnade traveled widely in researching and writing his book, highlighting people of all races and political views living in a broad range of communities, urban as well as rural.

Dignity has received most of its initial review attention and praise from conservatives. That's in part because it was published by Sentinel, the conservative imprint of Penguin Books. But to dismiss the laudatory response, including Hawley's, as an expression of partisanship is to miss what's most important about it. A conservative publisher, a wide range of conservative writers, and the conservative Republican senator from Missouri are all supporting a book that powerfully indicts economic policies pursued and defended by a long line of Republican presidents and lawmakers. (That many of those policies were also endorsed by Democrats doesn't soften the point.)

That's a big deal — and a dramatic shift that could upend the political spectrum as we know it.

Of course it also might not amount to much. Progressive activists are right to raise pointed questions. Will Hawley and Republicans in his mold begin supporting unions and labor policies that favor workers? Will they start demanding that nominees for the federal courts demonstrate less deference toward the Chamber of Commerce? If not, it's hard to see how the latter-day defense of "the American middle" will amount to more than window dresses on the same old oligarchic agenda.

Progressives also have self-interested reasons to resist a Republican effort to remake the GOP in an economic populist image. (A Republican workers party could pose a much bigger electoral challenge to the Democrats than Trump's plutocratic nativism.) But the rest of us — those who want what's best for the country more than what's best for one of its parties — should be cautiously cheered. After nearly four decades, the Reaganite gospel has finally begun to loosen its grip on the Republican Party.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

How are Democrats turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonade?

How are Democrats turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonade?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION As the Trump administration continues to try — and fail — at indicting its political enemies, Democratic lawmakers have begun seizing the moment for themselves

-

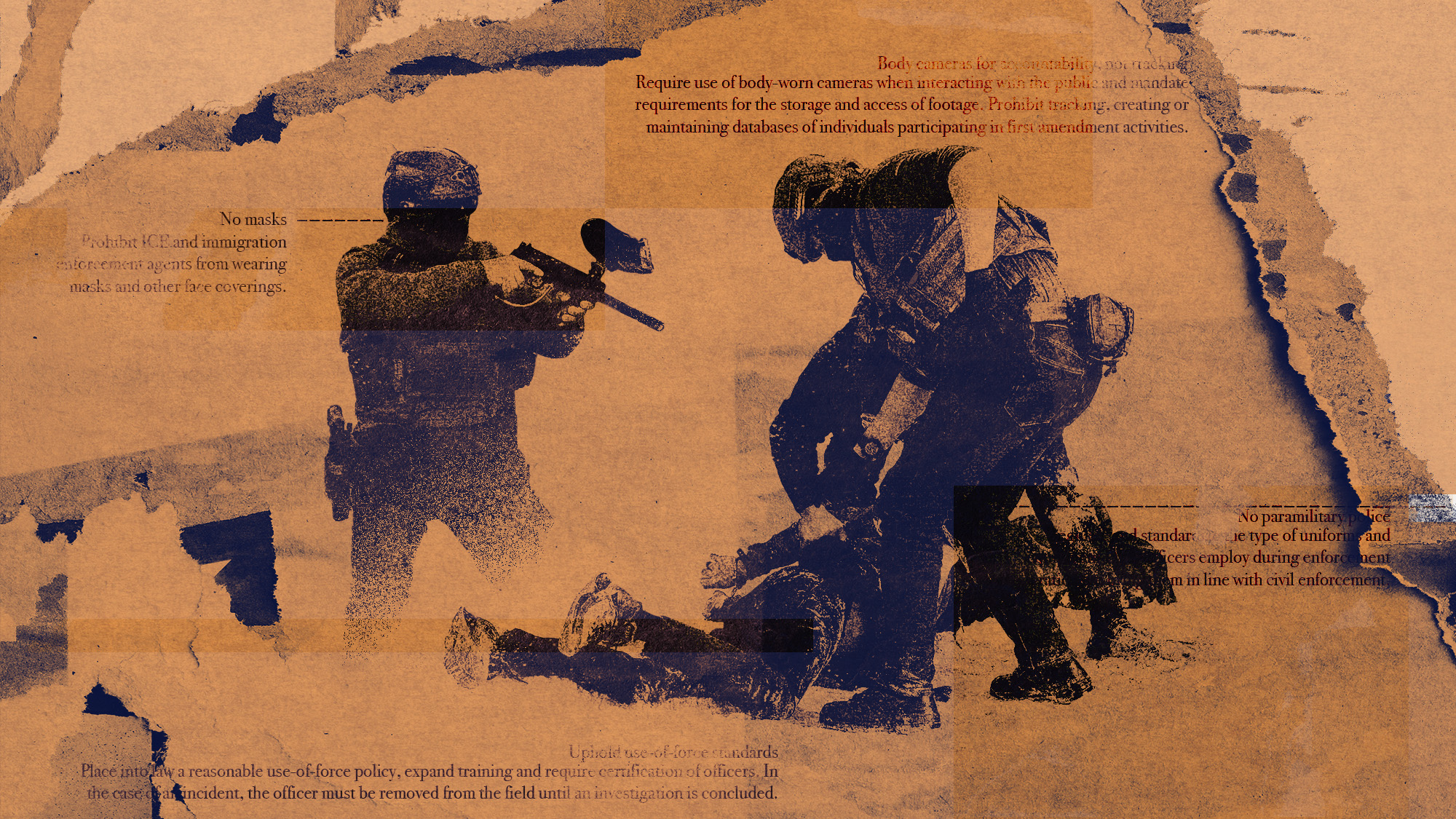

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?Today’s Big Question Democratic leadership has put forth several demands for the agency

-

Democrats push for ICE accountability

Democrats push for ICE accountabilityFeature U.S. citizens shot and violently detained by immigration agents testify at Capitol Hill hearing

-

Democrats win House race, flip Texas Senate seat

Democrats win House race, flip Texas Senate seatSpeed Read Christian Menefee won the special election for an open House seat in the Houston area

-

Is Alex Pretti shooting a turning point for Trump?

Is Alex Pretti shooting a turning point for Trump?Today’s Big Question Death of nurse at the hands of Ice officers could be ‘crucial’ moment for America

-

‘Dark woke’: what it means and how it might help Democrats

‘Dark woke’: what it means and how it might help DemocratsThe Explainer Some Democrats are embracing crasser rhetoric, respectability be damned

-

How realistic is the Democratic plan to retake the Senate this year?

How realistic is the Democratic plan to retake the Senate this year?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION Schumer is growing bullish on his party’s odds in November — is it typical partisan optimism, or something more?