The 2010s were an economic disaster

Policymakers from both parties completely blew it in the aftermath of the financial crisis and the Great Recession

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

As 2019 comes to a close, American policymakers must face a harsh truth: The last decade was an economic disaster. If the 2020s are going to be any better, our leaders will have to learn from their mistakes — or simply be replaced.

For all the talk of recovery, this decade began with the worst economic collapse since the Great Depression. Unemployment spiked to 10 percent, and it took most of the last ten years for it to come back down. As nice as a 3.5 percent unemployment rate is, it's also something that almost never happens.

Furthermore, our current good times look a less good under the surface. The government's definition of unemployment can leave out a lot of people. This year, the portion of people who got jobs each month who wouldn't even have been counted among the unemployed the month before reached 75 percent. That's by far the highest it's been in the last three decades. The percentage of working-age Americans who have jobs only returned to its pre-Great Recession peak in the last few months. (It still has a ways to go before it returns to its previous peak, just before the 2001 recession.)

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Beyond that, job quality — in terms of pay, benefits, hours, security, and more — has also deteriorated. Employment may be widely available again, but a lot of that employment is fundamentally worse than it was in decades past. Americans' wages still aren't growing as fast as they were before the crash, according to both the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Atlanta Fed. In fact, the Atlanta Fed finds that wage growth's peak in 2007 never got as high as its peak in 2000 — a similar pattern to prime-age employment. In the 2010s, productivity growth — the rate at which the economy learns to create more value with less inputs — also fell lower than it's been in decades. (Though it may finally be picking up again.)

Finally, if you look at economic output just before the Great Recession and draw a line continuing that growth at the same trend, it turns out the 2010s didn't close the gap at all. Once the recovery from 2008 began, the economy just started growing again at a permanently lower trend line. Trillions-worth of annual economic activity — jobs, wealth creation, living standards — simply vanished this decade, with no sign we will ever recover.

To a large extent, all of these problems boil down to a failure to run the economy hot enough. There was never enough spending out there to justify hiring everyone who wanted to work; which meant businesses were never under pressure to raise wages to compete with each other for labor, or to raise their productivity to stay ahead of rising labor costs.

How did this happen?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

First off: government spending. Public investment in things like infrastructure, research and development, education, and more is an enormous source of demand for the economy. Same goes for the welfare state, which supplies Americans with hundreds of billions to collectively spend. Indeed, a lot of welfare state spending is designed to automatically increase during recessions — providing economic recoveries with extra juice.

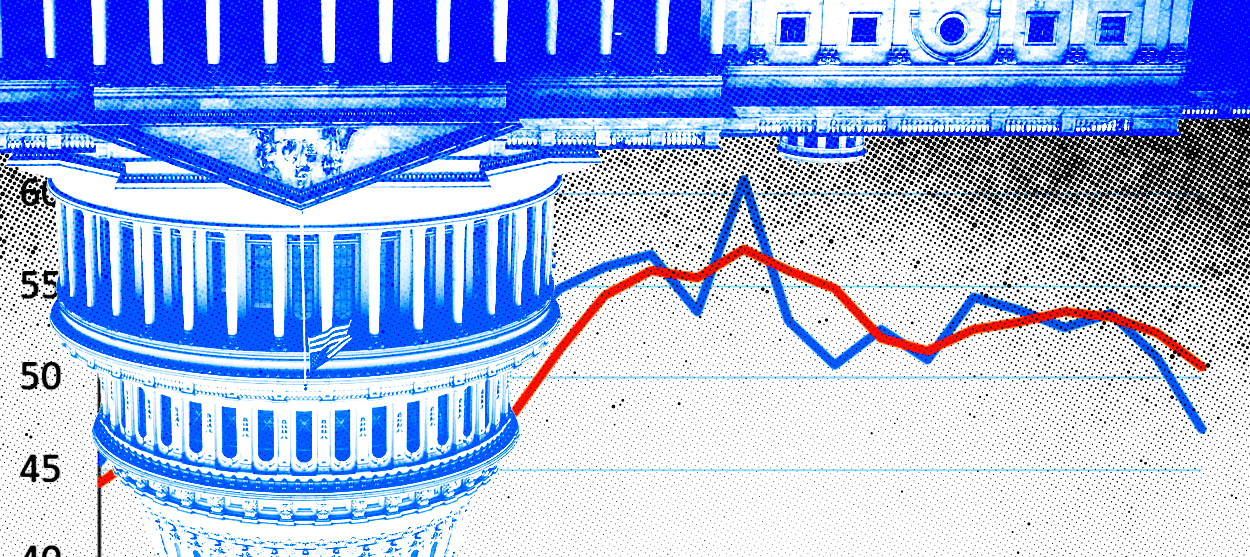

At the very beginning of the 2010s, government spending contributed to a big chunk of economic growth, as the 2009 stimulus played out and social programs like unemployment benefits and food stamps kicked in. But from late 2010 to 2015, the government cut back severely, and for the most part fiscal policy became a net drag on the economy. Left without federal support, state governments reduced their own spending, which undercut the recovery even more. From 2015 to 2017, the government ceased harming the economy, and after 2017 federal spending became a significant positive contributor to growth again. But by then the damage was done.

We can lay a lot of blame for this on the Republican Party, which was mendaciously hell-bent on austerity when Democrats held the White House, but happy to strike big spending deals once they were back in power. But President Obama was talking up the supposed debt crisis as early as 2011; his various economic officials are still pounding the austerity drums under Trump; Democratic House Speaker Nancy Pelosi is a fan of pay-for rules, which would effectively neuter the stimulative power of new spending. And of course the Democrats remain terrified of ambitious spending proposals from the likes of Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren.

The other problem was monetary policy. In its defense, the Federal Reserve did cut interest rates to zero soon after the Great Recession, in an effort to boost the economy. More recently, it's begun cutting rates again, in recognition of the recovery's tepidness. But in between, the Fed started hiking interest rates far too soon. Moreover, the entire interaction between Fed interest-rate policy and Congress' fiscal policy was corrupted by a failure to realize the limits of what monetary policy can achieve on its own.

The thing that links most all of these mistakes was a wildly unjustified pessimism among experts and policymakers concerning how hot the economy could run. Potential GDP was repeatedly revised down, and everyone assumed spending needed to be cut back and interest rates raised lest inflation take off. During the 2016 election, mainstream progressive economists openly mocked their heterodox peers for suggesting the economy was much further below full capacity than everyone thought.

At this point, policymakers should take a stance of radical humility on these questions. We should assume we are below full capacity and should keep stimulating until inflation has steadily risen by a few percentage points. Congressional fiscal policy should dramatically expand public investment and the automatic stabilizers of the welfare state, and should deliberately aim to overheat the economy. The Fed can shave whatever's necessary off the top to keep us at full capacity without going over. Politicians in both parties should drop the deficit hysteria — or at minimum the Democrats should refuse to be trolled by the GOP on the subject.

Simply put, U.S. policymakers from both parties completely blew it during the 2010s. Our government has enormously powerful tools at its disposal to drive economic growth and recoveries. But due to a combination of bad theory, foolish assumptions, raw ideological blindness and outright mendacity, those tools were never put to proper use.

The good news is the 2020s are an opportunity to do better.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred