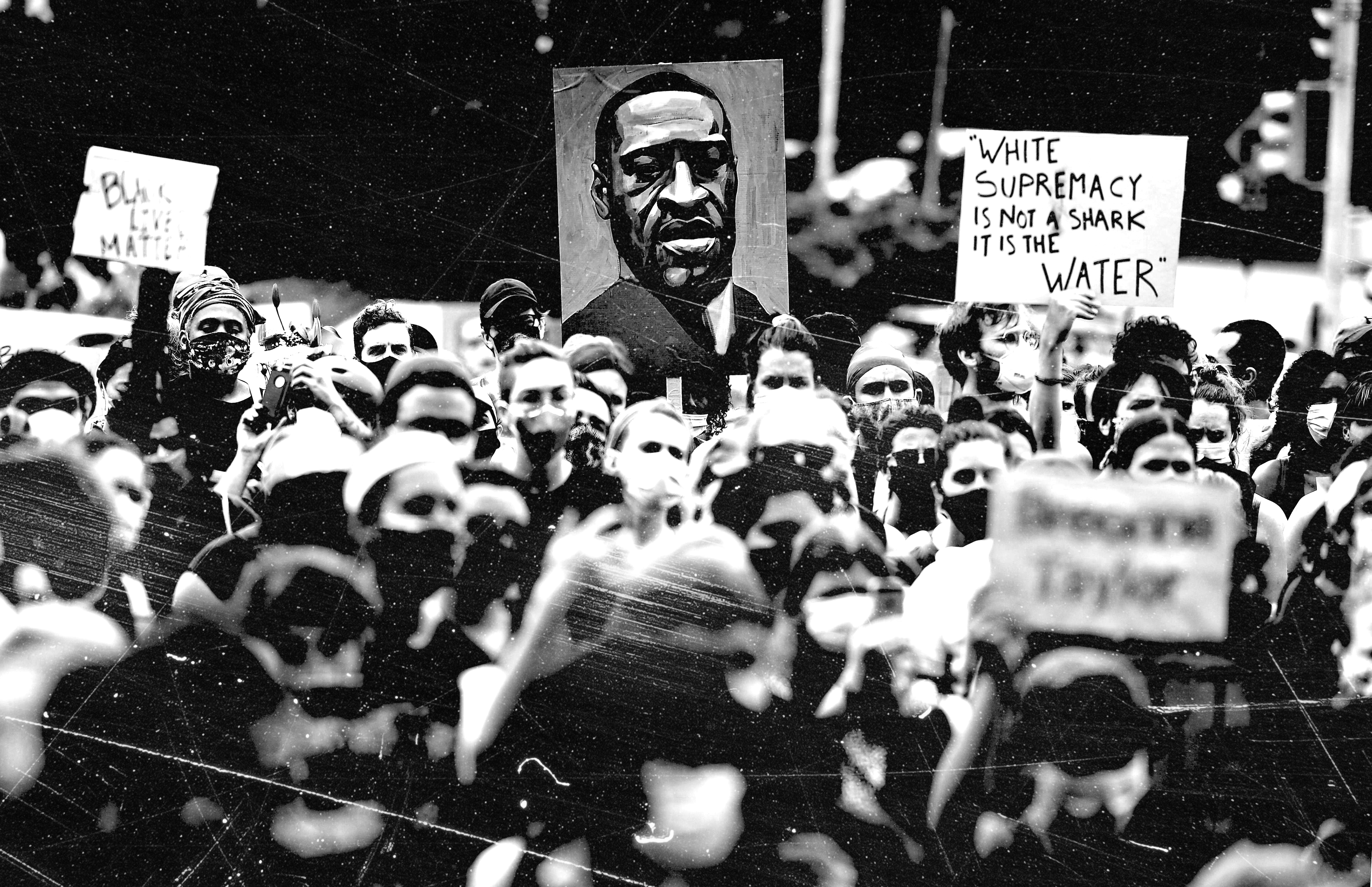

Manslaughter or murder in Minneapolis?

The George Floyd trial begins with a legal dilemma

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The trial of former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin for his part in the death of George Floyd last year began Tuesday. It will continue with jury selection this week — probably. Proceedings may be delayed in connection to a pending appeals court ruling about exactly how Chauvin will be charged: Will a previously removed third-degree murder charge be added, as prosecutors want, back to his current charges of second-degree manslaughter and second-degree murder?

Whatever the answer, this catchall approach to charging Chauvin strikes me as a strategic mistake. Giving the jury so many options can be a source of confusion, making unanimity on any one charge more difficult to achieve. More importantly, however, I've revisited Minnesota statutes for all three crimes, and I suspect that given these legal realities, at least the second-degree murder charge is a reach.

That's a problem if we're interested in restraining police violence, which I most definitely am. Until the U.S. has enacted as-yet unrealized reforms — eliminating qualified immunity, implementing stricter police use of force policies, reining in police unions, assigning officers at least some personal financial liability, unwinding overcriminalization, and much more — prosecutors need to be more strategic in charging errant cops.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Prosecutors who want to hold police accountable should seek the bird in the hand, not the two in the bush. They should select charges in these cases so that conviction is a real possibility and, therefore, a real constraint on future police behavior. One "guilty" verdict on manslaughter will do more to reshape officers' behavioral calculus than an endless stream of "not guilty" decisions on murder.

In the Chauvin case, "guilty" for one of the two murder charges isn't impossible, but I will be surprised if it happens, particularly given the plethora of competing expert testimony this trial will involve. That's not because what Chauvin did wasn't a grave wrong. It was. But legal and moral language don't always match. In this case, I'm hard-pressed to see how prosecutors will successfully demonstrate that what Chauvin did fits our state's legal definitions of second- or third-degree murder.

It's worth reviewing those definitions. With the second-degree unintentional murder charge, prosecutors will argue Chauvin "cause[d] the death of a human being, without intent to effect the death of any person, while committing or attempting to commit a felony offense." The problem will come in that final clause: Was Chauvin committing or attempting to commit a felony offense? The prosecutors say yes, he was committing assault.

But the Minneapolis Police Department specifically trained its officers to use neck restraints like the one Chauvin used on Floyd. At the time, neck restraints in which an officer would "[compress] one or both sides of a person's neck with an arm or leg" were permitted for 25 minutes, far longer than the nine minutes Chauvin pinned Floyd. Chauvin had been on the force for two decades and had repeatedly used this technique in past arrests. He wasn't fired or prosecuted for those prior uses because he was following MPD rules. And given those very rules, it's difficult to see how prosecutors will make the legal (not moral) case that Chauvin attempted felony assault and committed second-degree murder in the process. (MPD policy has since been updated to prohibit neck restraints and chokeholds.)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The third-degree murder charge is an easier fit. The task here is to show that Chauvin "without intent to effect the death of any person, cause[d] the death of another by perpetrating an act eminently dangerous to others and evincing a depraved mind, without regard for human life." (The sticking point under consideration at the appeals court, incidentally, is the part about the act being "dangerous to others" — that is, was Chauvin's behavior dangerous only to Floyd or to multiple "others"? One judge said the apparent danger to Floyd alone made this charge inappropriate, but there's precedent to reverse that call.)

This one seems feasible to me. Or, perhaps I should say: It would be feasible were Chauvin not a police officer, to whom American juries routinely show remarkable deference. Yet again that MPD neck restraint policy is going to be a problem. The department labeled it a "[n]on-deadly force option," which gives Chauvin's defense team room to argue that so far from being reckless about human life, he deliberately chose a restraint designed to preserve life.

If you've seen the videos of Chauvin's conduct during the last moments of Floyd's life, you might think that's BS. But that doesn't mean it can't be a persuasive legal argument in an environment already friendly to police. The jury will be advised to consider how hard it is to work in law enforcement, to reject the judgments of hindsight and only consider what Chauvin could know in the moment. If jurors decide Chauvin truly didn't realize the extent of Floyd's distress, they might decline to say he acted "without regard for human life." That means "not guilty" on murder in the third degree.

Last is the second-degree manslaughter charge. Minnesota law defines this crime as causing death "by the person's culpable negligence whereby the person creates an unreasonable risk, and consciously takes chances of causing death or great bodily harm to another."

This is a far lower bar to clear, and the MPD neck restraint policy is much less of an impediment. Perhaps it could even be argued that the department admitted the risk inherent in the move by advising officers to avoid crushing people's airways and, after restraint was complete, to move them into a recovery position. (Chauvin did not put Floyd in that position.) I think this conviction is attainable.

If that's all prosecutors attain, though, the anger and disappointment will be immense, and understandably so. In a strictly moral analysis, I think Chauvin's action did rise to the level of murder. And it's exactly that belief which makes me prefer the comparative certainty of the manslaughter charge over the legal stretch to murder charges. Give me that bird in the hand. Some justice is better than none, and even unsatisfactory legal accountability would do more to prevent future police misconduct than another cop walking away from brutality unpunished.

Bonnie Kristian was a deputy editor and acting editor-in-chief of TheWeek.com. She is a columnist at Christianity Today and author of Untrustworthy: The Knowledge Crisis Breaking Our Brains, Polluting Our Politics, and Corrupting Christian Community (forthcoming 2022) and A Flexible Faith: Rethinking What It Means to Follow Jesus Today (2018). Her writing has also appeared at Time Magazine, CNN, USA Today, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, and The American Conservative, among other outlets.