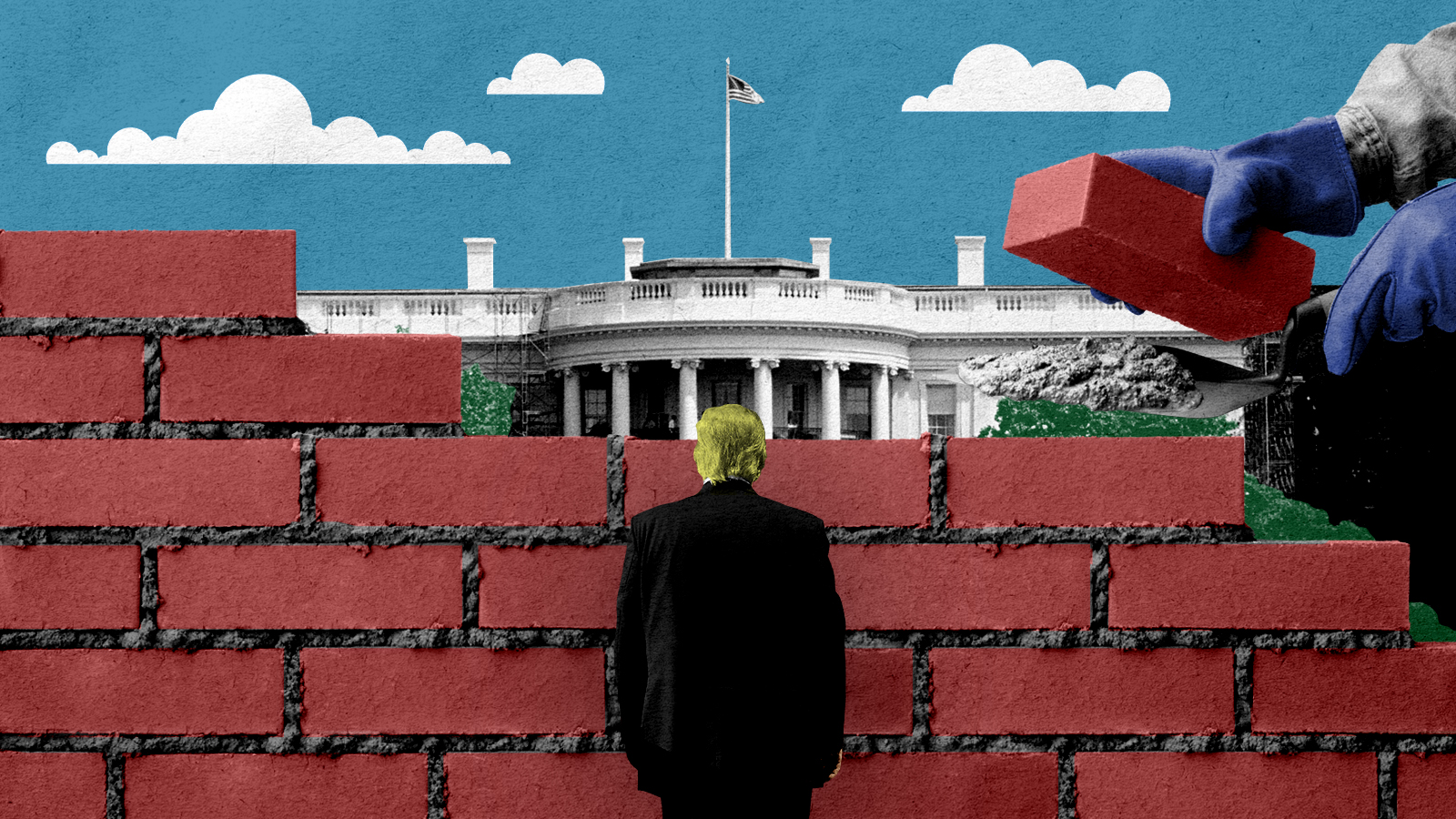

Democrats want to bar Trump from office using the 14th Amendment. Will it work?

How a post-Civil War era rule could keep Trump out of the White House for good

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Following months of self-fueled speculation, former President Donald Trump made it official on Tuesday and announced his candidacy for a second term in the White House. And while his third run for office will take place under decidedly different circumstances than his first two bids for the presidency, he remains a uniquely potent force in conservative politics and, for now, stands as the dominating frontrunner for the Republican nomination.

Faced with the very real prospect of a twice-impeached former president returning to office after instigating the Jan. 6 attack on the United States Capitol, some congressional Democrats — as well as several government accountability groups — have begun exploring whether they can bar Trump from the White House entirely. Their plan? Use a century-and-a-half-old constitutional amendment crafted in the wake of the Civil War.

Here's everything you need to know:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What is the 14th Amendment?

Written in the wake of the Civil War as part of the Reconstruction effort to repair the rift between northern and southern states, the 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution deals primarily with questions of citizenship and the rights thereof. Crucially, it also states in Section Three that:

No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice-President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof.

That prohibition on holding federal office was diluted by a series of subsequent congressional acts offering amnesty for many of those who would have otherwise been affected by the clause for their participation on the Confederate side of the Civil War. Still, the Amendment remained on the books, and has increasingly been seen by some Democrats and liberal-leaning groups as the most obvious means of preventing lawmakers who participated in the Jan. 6 attacks from remaining in, or entering, higher office.

Has it been used before?

Yes, but rarely. In the early 20th century, Wisconsin socialist Victor Berger was successfully blocked from assuming a seat in the U.S. House for having advocated against American involvement in World War I. He appealed the decision and, after the Supreme Court ruled in his favor, went on to several terms in office.

More recently, lawsuits brought against Reps. Marjorie Taylor Green (R-Ga.) and Madison Cawthorn (R-N.C.) attempting to bar them from re-election in the 2022 midterms relied heavily on the 14th Amendment and the pairs' anteceding behaviors in the run-up to the Jan. 6 insurrection. In both cases, the suits were blocked or found insufficiently convincing to actually apply to the two representatives. However, a similar suit successfully removed Jan. 6 participant Couy Griffin from his position as Otero County, New Mexico, commissioner this past September, with District Court Judge Francis Mathew noting that the events of that day met the definition of "insurrection."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"Because state law required Mr. Griffin to take an oath to support the Constitution as a county official, and he did so, the Court concludes he is subject to disqualification under Section Three," Mathew wrote in his ruling.

Sounds iffy, doesn't it?

Legal experts agree. "We could have 51 jurisdictions coming out differently, really, on the same evidence," former Judge Marcy Kahn told Bloomberg in a recent interview on the Amendment's potential efficacy against Trump. "It really would be a constitutional crisis."

This past year, Kahn served as the chair of the New York City Bar's Task Force on the Rule of Law, which authored a study on whether or not the 14th Amendment could be applied to Jan. 6 participants. That study, published in September, determined that "a uniform federal standard for application of Section Three is sorely needed" to address the obvious disparities and "eliminate ambiguity and confusion" in state and local interpretations of the clause. "[A] federal civil enforcement statute … would assure a reasoned, evidence-based, due process approach to candidate disqualification," the study further concluded in a call for Congress to enact its recommended reforms.

University of Indiana law professor Gerard Magliocca offered a similar sentiment in an essay published this past spring in response to the Federal District Court's decision allowing Cawthorn to remain on the ballot due to the Amnesty Act of 1872. "The Court ruled that a ballot challenge brought against Rep. Cawthorn by state voters under Section Three of the 14th Amendment could not proceed because Congress gave him amnesty 150 years ago," Magliocca wrote, adding, "if that conclusion sounds ridiculous, that's because it is."

Like Kahn, Magliocca concludes that the solution lies ultimately in the federal arena, writing "Congress can give Section Three amnesty to the Jan. 6th insurrectionists. But only this Congress or a future one may do so."

So where does this leave Trump?

It's unclear. While Trump was cleared of his role in the Jan. 6 insurrection during his second impeachment trial, the letter being circulated by Rep. David Cicilline (D-R.I.) in response to the former president's campaign announcement leans on subsequent testimony and evidence presented over the course of the Jan. 6 Committee hearings as the legal justification for his proposed legislation.

If Congress does pass Cicilline's bill, it would almost certainly be challenged by the former president's legal team, who have shown a willingness to elevate any legal threats to the conservative-leaning United States Supreme Court. What's more, the incoming Congress — which seems virtually certain to hold a slight Republican majority — could also move to counteract any legislation passed in the waning days of the current session.

Rafi Schwartz has worked as a politics writer at The Week since 2022, where he covers elections, Congress and the White House. He was previously a contributing writer with Mic focusing largely on politics, a senior writer with Splinter News, a staff writer for Fusion's news lab, and the managing editor of Heeb Magazine, a Jewish life and culture publication. Rafi's work has appeared in Rolling Stone, GOOD and The Forward, among others.

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Kurt Olsen: Trump’s ‘Stop the Steal’ lawyer playing a major White House role

Kurt Olsen: Trump’s ‘Stop the Steal’ lawyer playing a major White House roleIn the Spotlight Olsen reportedly has access to significant US intelligence

-

How are Democrats turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonade?

How are Democrats turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonade?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION As the Trump administration continues to try — and fail — at indicting its political enemies, Democratic lawmakers have begun seizing the moment for themselves

-

Trump’s EPA kills legal basis for federal climate policy

Trump’s EPA kills legal basis for federal climate policySpeed Read The government’s authority to regulate several planet-warming pollutants has been repealed

-

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffs

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffsSpeed Read Six Republicans joined with Democrats to repeal the president’s tariffs

-

Bondi, Democrats clash over Epstein in hearing

Bondi, Democrats clash over Epstein in hearingSpeed Read Attorney General Pam Bondi ignored survivors of convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein and demanded that Democrats apologize to Trump

-

Judge blocks Trump suit for Michigan voter rolls

Judge blocks Trump suit for Michigan voter rollsSpeed Read A Trump-appointed federal judge rejected the administration’s demand for voters’ personal data

-

US to send 200 troops to Nigeria to train army

US to send 200 troops to Nigeria to train armySpeed Read Trump has accused the West African government of failing to protect Christians from terrorist attacks