Democrats can prevail in the culture war. But they won't like the winning move.

'It's the economy, stupid' isn't enough right now

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

"Dems should treat cultural arguments as winnable."

This assertion by Greg Sargent of The Washington Post may well be true. But if so, it marks a break from longstanding conventional wisdom and would require far more circumspect politicking than Democrats have shown themselves capable of recent years.

Going back at least to Bill Clinton's first presidential campaign, Democrats have won the White House by following strategy laid out in a slogan Clinton campaign manager James Carville popularized in 1992: "It's the economy, stupid."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

That year, Clinton was challenging incumbent President George H. W. Bush during a recession — but even without unemployment rates above 7 percent, the strategy made sense and has continued to make sense for three decades. Material worries matter to lots of people, and the GOP's preferred economic policies (tax cuts for the rich, fewer government services, and lighter regulations on business) are bad for most voters.

But Republicans have learned to respond to Democratic strength on economics by running on culture war issues. This was true to some extent in the early 2000s, when Thomas Frank wrote What's the Matter with Kansas?, a book about the GOP's remarkably successful strategy of persuading voters in the American heartland to disregard their apparent economic interests in favor of waging comparatively trivial cultural battles. But it's become even truer since Donald Trump won the presidency with a campaign fueled almost entirely by cultural grievance.

Sargent's claim is that the right has gone so far in this direction, staking out positions well outside the cultural mainstream, that Democrats can and should try to turn cultural issues into a liability for Republicans.

Will it work? As I've recently argued myself, one would think so.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

On abortion, where polls consistently show strong majority support for keeping the procedure legal in all or most cases, a series of Republican states have passed draconian restrictions combined with highly unusual and distressing enforcement mechanisms designed to evade court challenges.

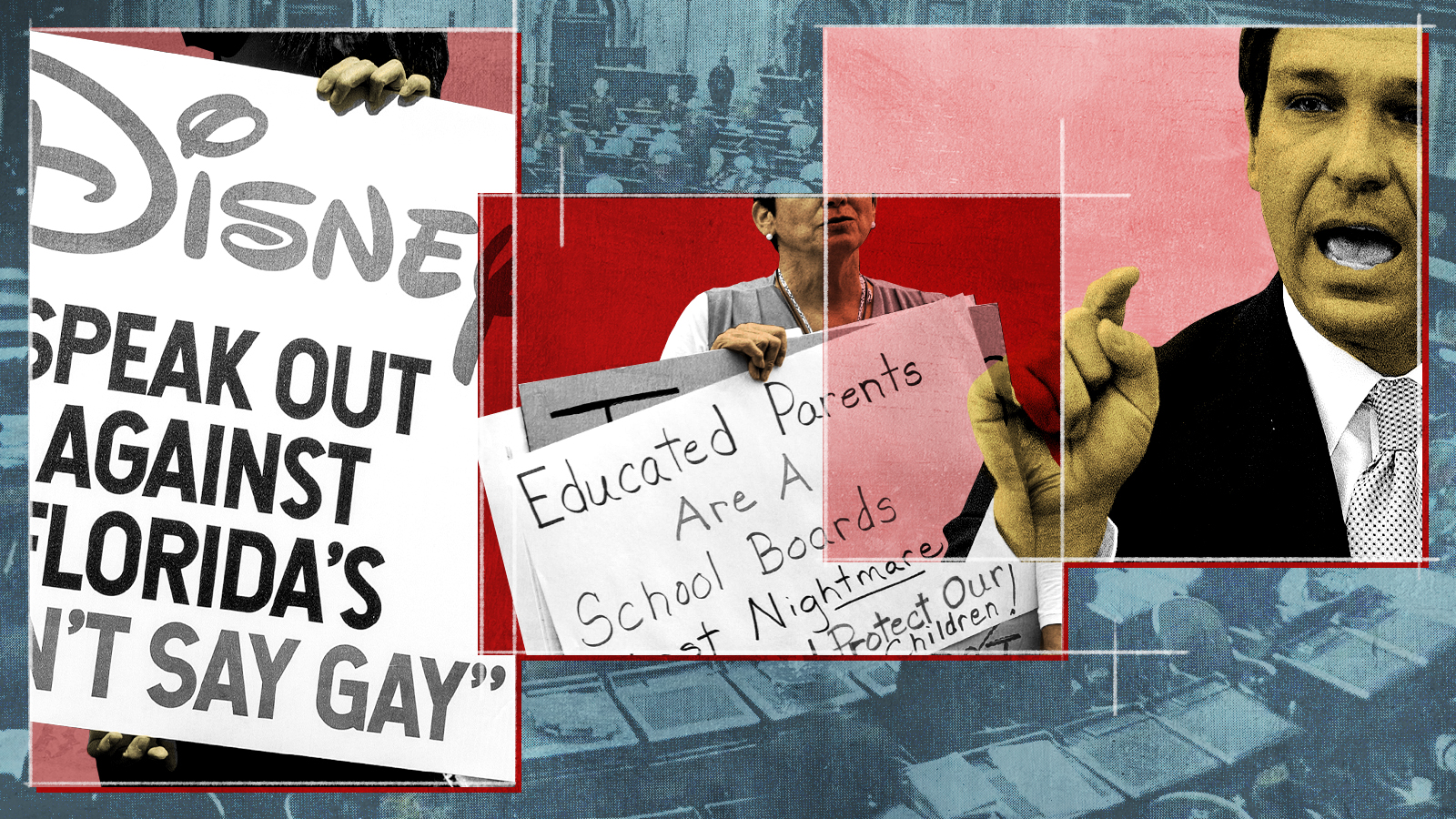

At the same time, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) has championed a state law restricting what teachers can say to children in public school classrooms about sex and gender. The vague wording of the law seems designed to invite overreaching in more conservative school districts and lots of headline-grabbing court challenges across the state. (Well over a dozen other states are now following DeSantis' lead.)

Meanwhile, the popular right-wing muckraker Christopher Rufo has unleashed a torrent of criticism against those who opposed passage of the Florida law, with special opprobrium directed at the Walt Disney Company for its strong (if late) stand opposing it. At first Rufo accused Disney of "grooming" kids for transgenderism and homosexuality. Then he claimed unusually large numbers of Disney employees have been fired over the years for actual sex abuse of children. And now he's begun to make the same claim about public schools in general.

That's a lot of vitriol and hyperbole emanating from the right. One might think it would spark a politically potent backlash, which is precisely what Sargent hopes and predicts. But will it?

We have reason to doubt it — because of the potent way the right currently deploys the fallacy of composition in its political messaging. That fallacy involves treating a handful of examples as exemplary of a whole population. Do all or even most Democrats think women can have penises? Or that men can get pregnant? Or that it's sensible to introduce young kids to the idea that gender is entirely mutable, that boys can become girls and girls can become boys at will? Or that a child should be encouraged to take hormones or undergo surgery to transition from one gender to another? Or that parents should be punished if they resist such interventions?

I suspect very few Democrats would affirm these positions, just as very few teachers espouse these kinds of views in their classrooms. But some outspoken activists on the left do favor them, just as a small number of teachers probably do, too, while the far greater number who don't are inclined to keep their opposition to themselves for fear of making life harder for trans kids and adults.

All it takes for the right to insulate its hardball tactics from political blowback is for these outlier positions to be treated in "the discourse" as representative of the whole leftward side of the political spectrum. That's the fallacy of composition in action, and it's now second nature for Republican politicians and their most prominent media cheerleaders, who inject isolated stories of Democratic extremism from across the country into the cultural ecosystem every day.

If Democrats want to challenge Republicans on their preferred cultural terrain, then, they will need to couple strong and justified criticism of the right's overreaching with full-throated denials of its fallacious accusations. That means Democrats stating clearly and repeatedly that they don't favor the positions on gender fluidity and medical interventions for children that the right claims they do.

If Democrats can't or won't do that, any effort at pushback on culture will fail. And with inflation making an economic message tricky, too, refusing to stake out a more centrist position may ensure Democrats lose more than the culture war.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

How are Democrats turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonade?

How are Democrats turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonade?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION As the Trump administration continues to try — and fail — at indicting its political enemies, Democratic lawmakers have begun seizing the moment for themselves

-

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?Today’s Big Question Democratic leadership has put forth several demands for the agency

-

Democrats push for ICE accountability

Democrats push for ICE accountabilityFeature U.S. citizens shot and violently detained by immigration agents testify at Capitol Hill hearing

-

Democrats win House race, flip Texas Senate seat

Democrats win House race, flip Texas Senate seatSpeed Read Christian Menefee won the special election for an open House seat in the Houston area

-

Is Alex Pretti shooting a turning point for Trump?

Is Alex Pretti shooting a turning point for Trump?Today’s Big Question Death of nurse at the hands of Ice officers could be ‘crucial’ moment for America

-

‘Dark woke’: what it means and how it might help Democrats

‘Dark woke’: what it means and how it might help DemocratsThe Explainer Some Democrats are embracing crasser rhetoric, respectability be damned

-

How realistic is the Democratic plan to retake the Senate this year?

How realistic is the Democratic plan to retake the Senate this year?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION Schumer is growing bullish on his party’s odds in November — is it typical partisan optimism, or something more?