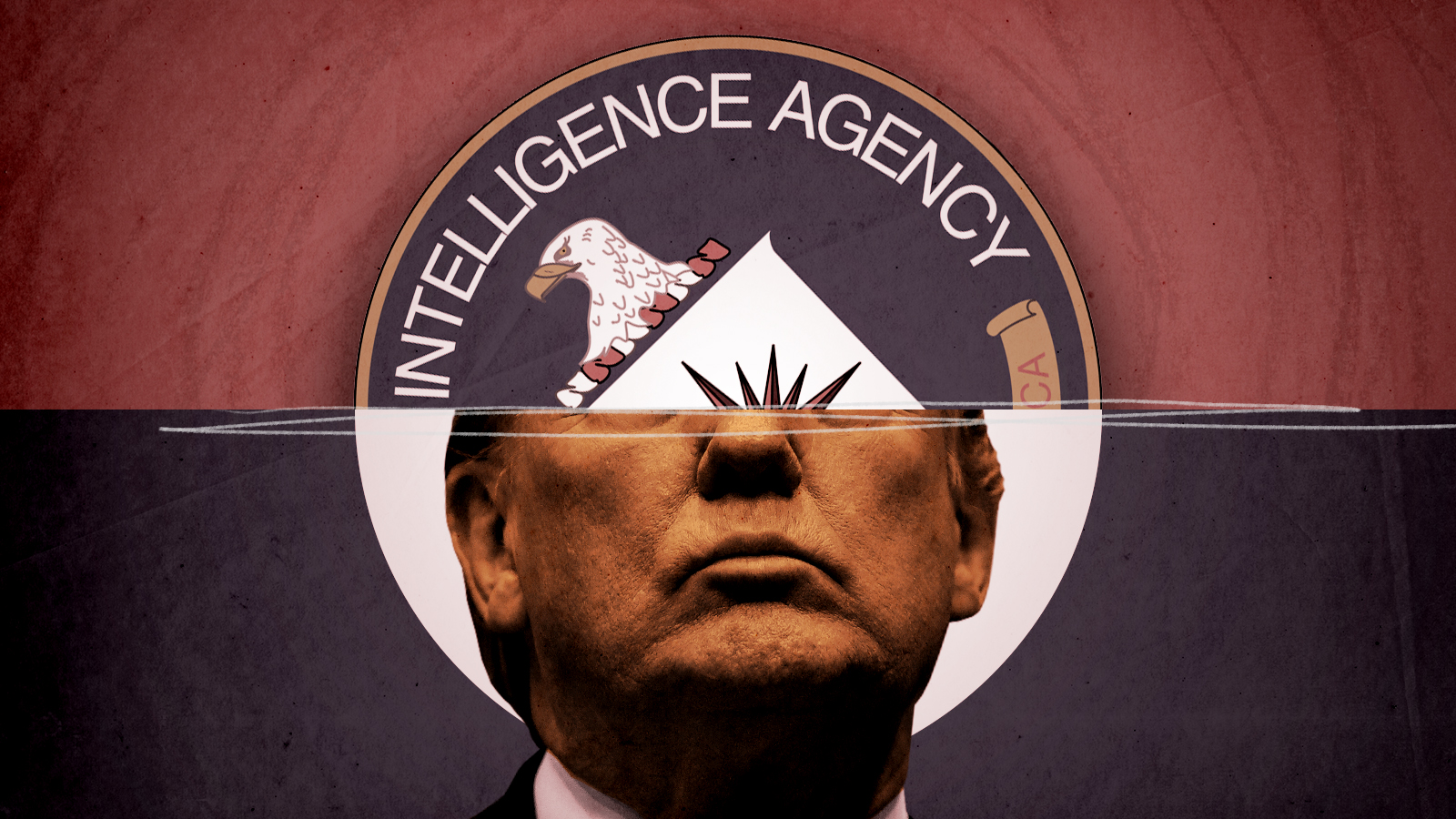

The right is finally ready to reform the CIA. Don't let hatred of Trump ruin it.

We shouldn't let partisanship foreclose an opportunity to rein in the intelligence establishment

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The intelligence community enjoys enviable status in popular culture. In shows like Homeland and films like the Jason Bourne series, the agency is presented as hyper-vigilant, super-competent, and brutally effective. Older works and period pieces place intelligence agents in a clubby, vaguely aristocratic milieu. Recent depictions emphasize their seamless immersion in foreign cultures and the high-tech resources they deploy, setting scenes in teeming souks and banks of shining computers.

By most journalistic and scholarly accounts, however, the reality is rather different. Studies like Tim Weiner's A Legacy of Ashes and Christopher Andrew's The Secret World depict an institution that has more in common with Office Space than with Sicario. A recent critique of sensationalized spy fiction notes that CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia resemble a "shabby post-office."

Even if the mystique is false, though, the powers the CIA wields are very real. In a letter to CIA Director William Burns and Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines that was written in April 2021 but declassified last Thursday, Sens. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) and Martin Heinrich (D-N.M.) request information about a previously unknown program that collected bulk data on American citizens without a warrant or other due process. According to the senators, the program stands "entirely outside the statutory framework that Congress and the public believe govern this collection, and without any of the judicial, congressional, or even executive branch oversight that comes from FISA [Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act] collection."

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In the wake of failures in Iraq (where inaccurate assessments were further hyped by the Bush administration), Afghanistan, and now, perhaps, Ukraine, the Wyden-Heinrich letter raises deeper questions about whether the intelligence community can be trusted to do its job within the law. After years of "Russiagate" controversy, public attitudes toward the CIA and its counterparts are still heavily influenced by opinions of former President Donald Trump — which means, among many Democrats, the intelligence establishment has accrued a certain deference not historically accorded from the left. But we shouldn't let partisanship foreclose an opportunity for clearly necessary reform.

Concerns about abuses of power by the CIA and other intelligence agencies are nothing new. In 2013, then-NSA contractor Edward Snowden revealed the existence of PRISM, a tool that allowed the government to collect user data from popular email and social media platforms. Two years later, Congress passed the USA Freedom Act, which reauthorized FISA while tightening restrictions on collection methods.

The Snowden controversy wasn't the first attempt to rein in the intelligence community, either. In 1975, a Senate select committee on intelligence led by Frank Church (D-Idaho) and its counterpart in the House of Representative gave the public a first sustained glimpse of the secret world. It was not a pretty picture. The Church Committee is best known for revealing attempts to assassinate foreign leaders as well as the mind-control program MKUltra. But many of its disclosures had to do with large-scale, warrantless domestic spying that prefigured more recent scandals.

What's new now is the evolving politics of the issue. In the past, critics of the intelligence community were mostly found on the left. For devoted anticommunists, legislative oversight handicapped efforts to defeat America's enemies. Church himself narrowly lost his seat in 1980 due in part to accusations that he had betrayed U.S. agents in the field. The pattern of liberal criticism and conservative defense mostly repeated itself in the Iran-Contra episode and the decade after the 9/11 attacks. Although many libertarians and paleocons — social conservatives skeptical of foreign wars and immigration alike — dissented, the right largely celebrated the expansion of intelligence budgets, activities, and powers.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

That's changed in the last few years. One reason for mounting skepticism among conservatives and Republicans is a delayed reaction to the failure of the so-called Global War on Terror. As recently as 2015, it was considered shocking among Republicans that Trump denounced the invasion of Iraq as a bloody, expensive disaster. "All smart people" knew the war was a mistake, Trump insisted during his presidential campaign, novel territory for a viable GOP presidential candidate.

More important, though, is the relation between the intelligence community and Trump himself. Faced with CIA reports that Russia had meddled in the election on his behalf, President-elect Trump characterized the agency as "the same people that said Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction." The controversy went on to dominate the first few years of his presidency. At length, it transpired that several accusations about Russian interference were derived from misuse of the FISA system, and although the main culprits were in the Justice Department rather than the CIA or other foreign intelligence service, the episode confirmed conservative hostility to the "deep state" and suspicion of domestic surveillance.

Like other government agencies, moreover, the intelligence community has been caught up in the culture war. Soon after President Biden took office last year, the CIA announced a marketing campaign intended to attract younger, hipper, and more diverse employees. The "Humans of the CIA" rebranding project was a PR bust. But it encouraged revisionist arguments that the agency was only briefly, if ever, the bastion of WASP propriety depicted in films like The Good Shepherd. At present if not in the past, many on the right concluded, the CIA is yet another branch of the cultural establishment threatening to make their lives intolerable.

The conservative turn against the secret world provoked a contrary reaction among Democrats. By the middle of Trump's administration, Democrats were more likely to express approval for the CIA and FBI than were Republicans. Some of this shift was a proxy for opinions of the president, yet it also reflected an unexpected and occasionally surreal reconfiguration of political values that elevated G-men and spooks into heroes of antiauthoritarian resistance.

But it would be a missed opportunity if different assessments of Trump undermined the ideologically mixed coalition to protect civil liberties and extend congressional oversight of the CIA. A bipartisan group of senators is already working on a legislative response, including a proposal to ban the sale of consumer data to intelligence and law enforcement agencies. And in journalism, popul-ish outlets like The American Conservative and The Federalist are running criticisms of the intelligence community that might once have been expected in The Village Voice.

We can argue about the 2016 election another day. Right now, reining in the CIA is an opportunity too good to miss.

Samuel Goldman is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also an associate professor of political science at George Washington University, where he is executive director of the John L. Loeb, Jr. Institute for Religious Freedom and director of the Politics & Values Program. He received his Ph.D. from Harvard and was a postdoctoral fellow in Religion, Ethics, & Politics at Princeton University. His books include God's Country: Christian Zionism in America (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018) and After Nationalism (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021). In addition to academic research, Goldman's writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and many other publications.