Stealing COVID aid

Billions in pandemic relief dollars were wasted or pocketed by scammers. How did that happen?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Billions in pandemic relief dollars were wasted or pocketed by scammers. How did that happen? Here's everything you need to know:

Was COVID relief successful?

In many ways, yes. It helped prevent what most economists agree would've been the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression. As the pandemic hit in the spring of 2020 amid a massive wave of hospitalizations and deaths, many businesses shut down or reduced operations and the U.S. economy lost more than 20 million jobs. Lawmakers scrambled to act, and in late March, President Trump signed the $2 trillion CARES Act, a sprawling package that included direct payments to households, enhanced unemployment insurance, and small-business loans. In March 2021, with millions still out of work, President Biden signed a second COVID relief bill, this one for $1.9 trillion. Under the Trump and Biden administrations, the federal government allocated $6 trillion toward pandemic relief. A Moody's Analytics report says these collective efforts saved the country from a major, double-dip recession. In the midst of a paralyzing pandemic, 2020 saw the biggest drop in poverty in five decades and no major increase in hunger. Once vaccines arrived, the economy rebounded briskly and unemployment hit record lows. "What the money did," said Louise Sheiner, an economist with the Brookings Institution, "was to basically make sure that when we could reopen, people had money to spend, their credit rating wasn't ruined, they weren't evicted, and kids weren't going hungry."

Was there a price for that success?

Yes. The San Francisco Fed estimates that trillions injected into the economy added as much as 3 percentage points to the inflation rate by late 2021. In addition, an alarming proportion of money was misspent or stolen. Of $873 billion in unemployment insurance distributed, a recent Labor Department report estimates that at least 1 in 6 dollars should not have been paid out, "with a significant portion attributable to fraud." Cybersecurity firm DarkTower discovered that more than 200,000 users of the messaging app Telegram belonged to groups that traded tips on the best states to target for unemployment money. Criminal networks in China, Nigeria, and elsewhere started identity-theft rings. Aid targeted to businesses fared little better. A University of Texas analysis of 11.8 million Paycheck Protection Program loans found a 15 percent fraud rate, potentially costing taxpayers more than $117 billion. About $3.9 billion in Small Business Administration (SBA) loans went to 57,000 entities on the Treasury Department's "do not pay" list.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How did that happen?

Scammers invented or misrepresented businesses to get loans. One 55-year-old Texan was later convicted of netting $24 million through 15 fraudulent loan applications; he spent some of the money on a Bentley convertible and a Corvette Stingray. A California businessman was charged with using $5 million in aid to buy a Lamborghini and a Ferrari. A family of Christian missionaries received $8.4 million from the SBA by falsely claiming to run a ministry with 486 employees and a $2.7 million monthly payroll.

Why the lack of oversight?

The government hadn't distributed aid on this massive scale before, and with millions of people and businesses hurting, it chose speed over precision. Many state unemployment agencies, hobbled by archaic, decades-old computer systems and understaffing from years of budget cuts, were quickly overwhelmed. Twenty states did not perform all the required background checks on applicants. The SBA, a congressional subcommittee found, may have approved 1.6 million loans without evaluating the applications. With loans rubber-stamped 500 at a time, even obvious red flags, such as overseas client locations, sometimes didn't prevent approval.

Can the money be recovered?

Only a small fraction of it. Federal authorities have so far recaptured $4 billion — less than 3 percent of wrongful payments — of unemployment money, and they have opened more than 1,150 investigations of potential misuse of various relief funds. Government and bank investigators have returned $10 billion in misallocated business relief to government coffers. But the vast majority of the fraud remains unpunished. The Justice Department lacks the resources to investigate and prosecute tens of thousands of perpetrators.

Was there a better way?

Governments around the world have spent more than $15 trillion on pandemic relief, but most countries did not offer direct cash to citizens regardless of need, as the U.S. did. Instead, they funneled the money to laid-off workers through their employers and existing welfare organizations. Some level of fraud was inevitable, but even compared with a previous stimulus, COVID spending was wildly inefficient. Only 0.6 percent of the $831 billion American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, for example, went to fraudsters. Strengthening, modernizing, and expanding government social safety net systems could make large-scale waste less likely in the next emergency, but George Washington University economics professor Tara Sinclair points out there isn't much appetite for spending billions now to prevent future fraud. It's hard to convince taxpayers, she said, that "if we do this, it'll look like a lot of money now, but the next time there's a crisis, we won't end up just spending a trillion or two, willy-nilly."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

How states spent their windfalls

Washington sent some $900 billion to state and local governments aiming to prevent fiscal catastrophe as their tax revenues plunged. But with few strings on how states could use the funds, some are spending them or using them to free up state money for projects with little or no connection to the pandemic. Alabama spent $400 million of pandemic money on building three new prisons. Florida dedicated a fifth of its $8.8 billion allotment to highway construction; one town in the state spent some of its allotment on a new golf course. California, which got $37.3 billion under the two rescue plans, had a $100 billion budget surplus in 2021 — some of which is being refunded to state residents. Federal law bars states from using the funds for tax cuts, but 21 states have challenged the prohibition in court — most of them successfully. "These states are awash in money — everybody from Kentucky to California," said Scott Jennings, a former aide to Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-Kentucky). And "if there's one thing a governor knows how to do, it's drive around their state and hand out huge checks."

This article was first published in the latest issue of The Week magazine. If you want to read more like it, you can try six risk-free issues of the magazine here.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillance

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillanceUnder the radar The disease can spread through animals and humans

-

Covid-19 mRNA vaccines could help fight cancer

Covid-19 mRNA vaccines could help fight cancerUnder the radar They boost the immune system

-

The new Stratus Covid strain – and why it’s on the rise

The new Stratus Covid strain – and why it’s on the riseThe Explainer ‘No evidence’ new variant is more dangerous or that vaccines won’t work against it, say UK health experts

-

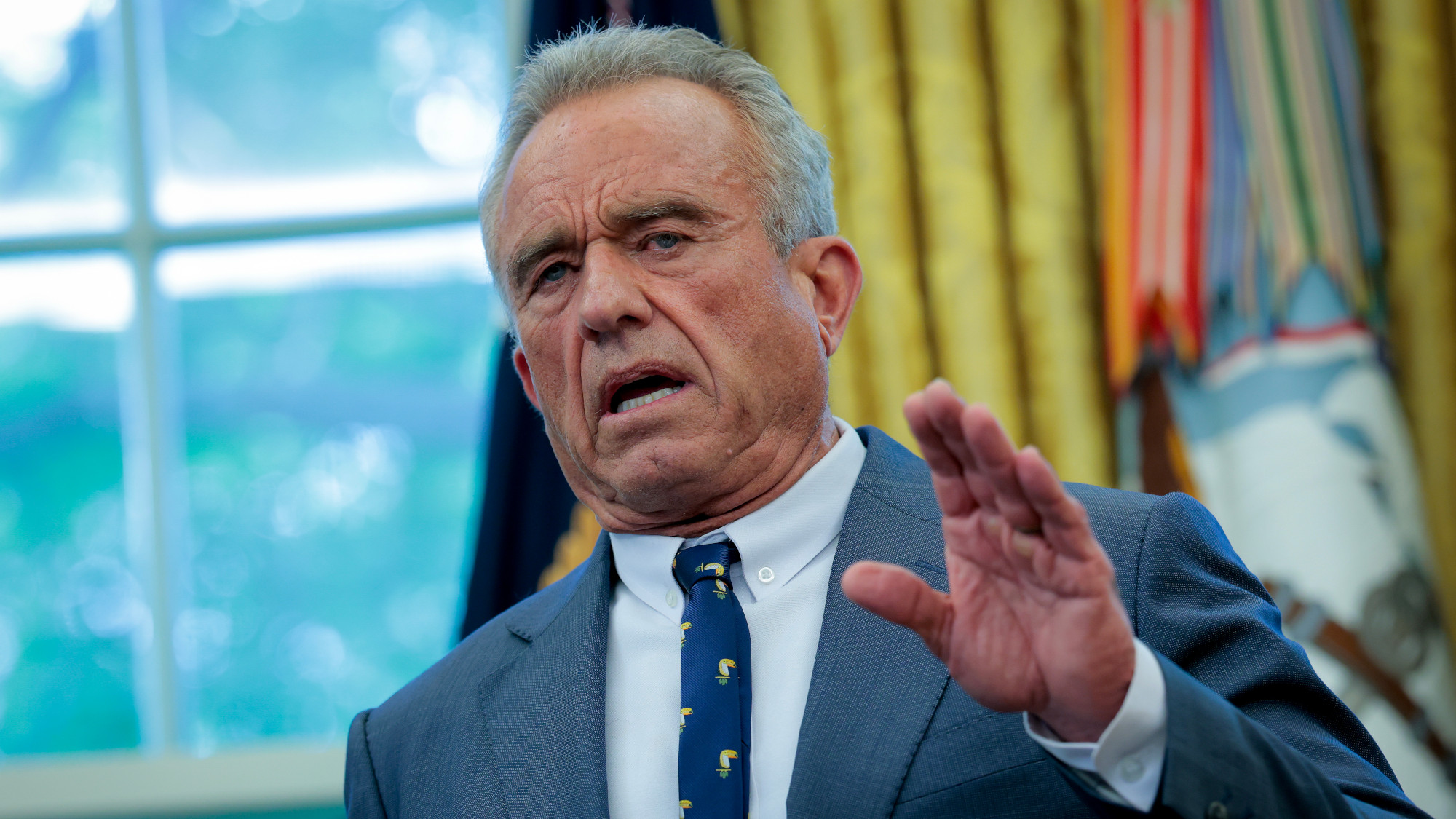

RFK Jr. vaccine panel advises restricting MMRV shot

RFK Jr. vaccine panel advises restricting MMRV shotSpeed Read The committee voted to restrict access to a childhood vaccine against chickenpox

-

RFK Jr. scraps Covid shots for pregnant women, kids

RFK Jr. scraps Covid shots for pregnant women, kidsSpeed Read The Health Secretary announced a policy change without informing CDC officials

-

New FDA chiefs limit Covid-19 shots to elderly, sick

New FDA chiefs limit Covid-19 shots to elderly, sickspeed read The FDA set stricter approval standards for booster shots

-

RFK Jr.: A new plan for sabotaging vaccines

RFK Jr.: A new plan for sabotaging vaccinesFeature The Health Secretary announced changes to vaccine testing and asks Americans to 'do your own research'

-

Five years on: How Covid changed everything

Five years on: How Covid changed everythingFeature We seem to have collectively forgotten Covid’s horrors, but they have completely reshaped politics