How carbon credits and offsets could help and hurt the climate

They could be allowing polluters to continue polluting

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The European Commission is set to permit countries to use carbon credits and offsets to "outsource a portion of their climate efforts to poorer countries from 2036," said Politico. They will also count toward the Commission's 2040 climate target. But while these credits and offsets have become a significant part of many countries' plans to reduce emissions and some claim any reduction of emissions is good regardless of location, others say the system allows polluters to keep polluting.

What are carbon credits and offsets?

Carbon offsets help "mitigate emissions" and are a "voluntary act by a company," said Earth.org. And carbon credits help prevent emissions and are "regulated and distributed by governments."

Both are "permits that allow the owner to emit a certain amount of carbon dioxide or other greenhouse gases," said Investopedia. This can apply on an individual level, national or global scale. Companies, for example, can purchase credits and offsets to bring down their own carbon footprint. ByteDance, the parent company of TikTok, "purchased more than 100,000 tons of carbon credits from Rubicon Carbon, a carbon management and investment company," to help reach its 2013 carbon neutrality goal, said Data Center Dynamics. In the global market, countries "unable to reduce enough greenhouse gas emissions through conventional methods would be able to purchase credits from other countries that implemented emission-reduction projects such as afforestation," said Earth.org.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

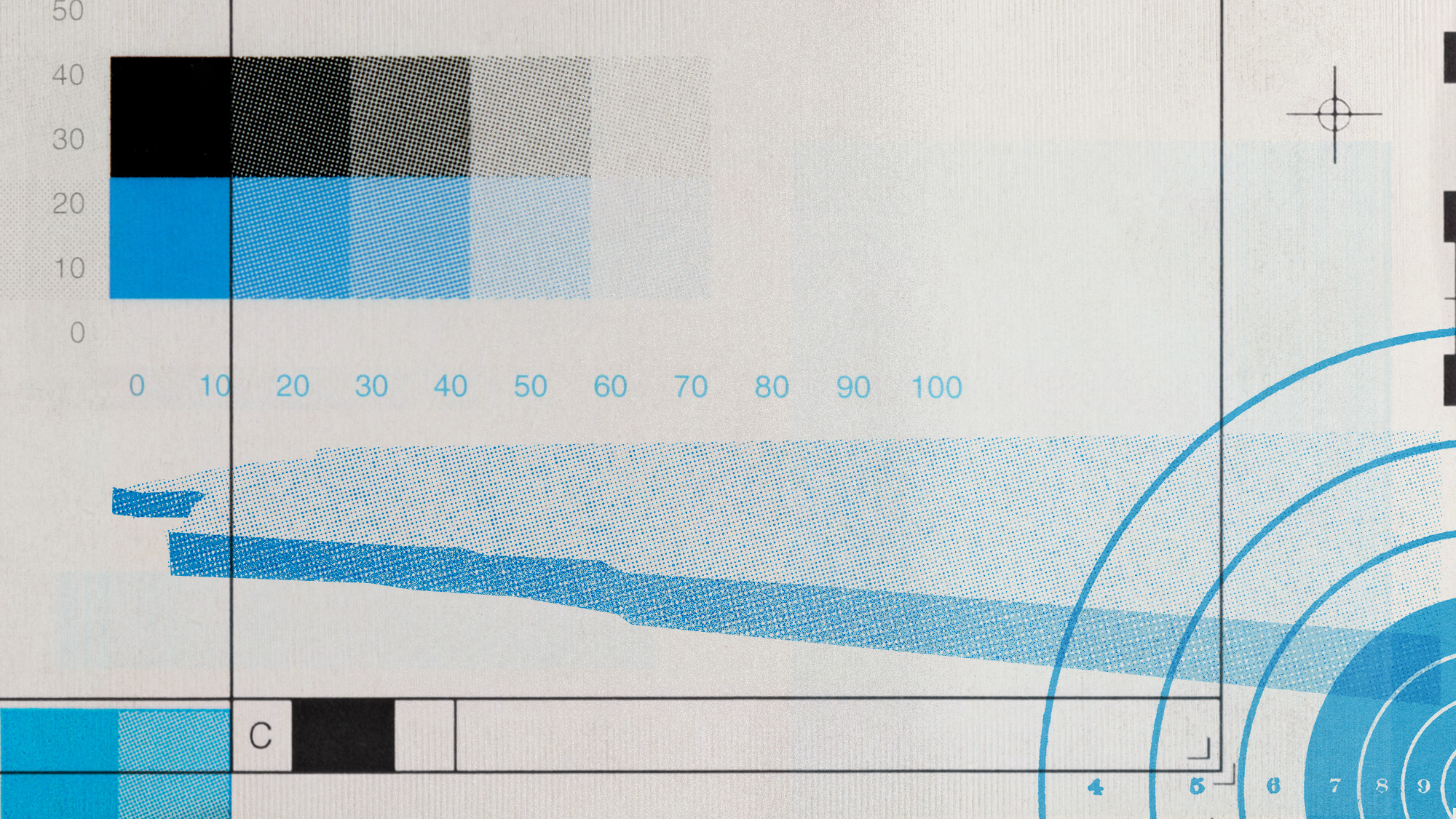

The carbon credit market usually works through a cap-and-trade system. The government sets a cap on the maximum emissions an industry or even an entire economy can produce. The cap is then divided into allowances that can be traded. The trade is a "market for companies to buy and sell allowances that let them emit only a certain amount, as supply and demand set the price," said the Environmental Defense Fund. Trading "gives companies a strong incentive to save money by cutting emissions in the most cost-effective ways." Another way to offset carbon emissions is by allowing emitters to invest in projects that reduce emissions in developing countries, which are not required to have targets.

Are they effective?

Carbon credits and offsets have become a staple in the fight against climate change but they have also faced scrutiny, with many questioning their effectiveness. On the one hand, they are a "way to raise funding for CO2-cutting projects in developing nations," said Reuters. They also "create a monetary incentive for companies to reduce their carbon emissions," and "those that can't easily reduce emissions can still operate but at a higher financial cost," said Investopedia. Ultimately, the "atmosphere doesn't care where the emissions reductions happen," said Barbara Haya, the director of the Berkeley Carbon Trading Project, to Science News.

Those opposed say that carbon credits and offsets distract from the true goal. "Achieving net zero should begin with every effort to eliminate or reduce the burning of fossil fuels, the main cause of global warming," said Science News. The existence of carbon offsets allows polluters to "continue to engage in practices that are systemically unsustainable," said Sentient Media. "There's a growing consensus among experts" that offsets are "not an effective tool for fighting climate change, and in some cases may do more harm than good." There is also evidence to suggest that "existing protocols do not ensure carbon credits are consistently real, high-quality and accurately represent 1 ton of avoided, reduced or removed emissions," said a study in the journal Earth's Future.

Carbon credits and offsets should perhaps be only a piece of the emission-reduction puzzle, not a substantial portion. "The amount is important, because it shows how much you change in your own economy," said Ana Toni, the CEO of the COP30 climate summit set to take place this November in Belém, Brazil, said to Reuters. "If it's really a big amount of (credits), you're not changing your own economy."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Devika Rao has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022, covering science, the environment, climate and business. She previously worked as a policy associate for a nonprofit organization advocating for environmental action from a business perspective.

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy

-

Book reviews: ‘Bonfire of the Murdochs’ and ‘The Typewriter and the Guillotine’

Book reviews: ‘Bonfire of the Murdochs’ and ‘The Typewriter and the Guillotine’Feature New insights into the Murdoch family’s turmoil and a renowned journalist’s time in pre-World War II Paris

-

The environmental cost of GLP-1s

The environmental cost of GLP-1sThe explainer Producing the drugs is a dirty process

-

The plan to wall off the ‘Doomsday’ glacier

The plan to wall off the ‘Doomsday’ glacierUnder the Radar Massive barrier could ‘slow the rate of ice loss’ from Thwaites Glacier, whose total collapse would have devastating consequences

-

Can the UK take any more rain?

Can the UK take any more rain?Today’s Big Question An Atlantic jet stream is ‘stuck’ over British skies, leading to ‘biblical’ downpours and more than 40 consecutive days of rain in some areas

-

As temperatures rise, US incomes fall

As temperatures rise, US incomes fallUnder the radar Elevated temperatures are capable of affecting the entire economy

-

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’The explainer Water might soon be more valuable than gold

-

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’Under the radar The gender gap has hit the animal kingdom

-

Why scientists want to create self-fertilizing crops

Why scientists want to create self-fertilizing cropsUnder the radar Nutrients without the negatives

-

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.Under the radar It is quickly melting away