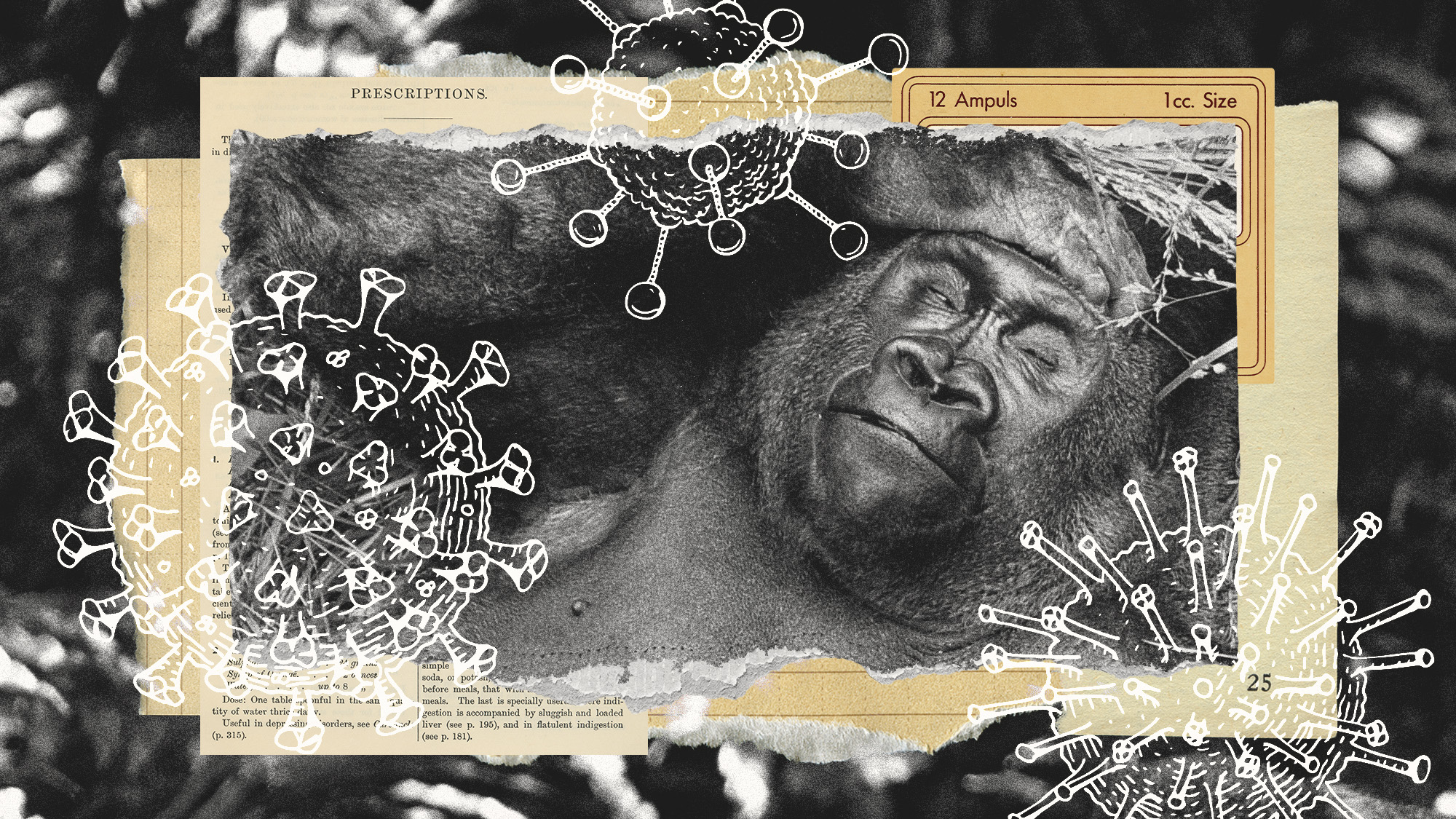

Chimpanzees are dying of human diseases

Great apes are vulnerable to human pathogens thanks to genetic similarity, increased contact and no immunity

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Humans threaten great ape populations by destroying habitats or poaching animals for zoos and meat – or it seems by infecting them with the common cold.

"For as long as humans have been domesticating animals, there have been zoonoses" – or the spread of infectious diseases from animals to humans – said the Emerging Pathogens Institute. Recently, public health emergencies like Covid-19 or avian flu have "thrust zoonoses back into the spotlight".

But the spread of human diseases to animals – known as "reverse zoonosis" – is a growing threat, often even bigger than habitat loss or poaching, said Nature. Humans have transmitted Covid-19 to "a panoply of species", but chimpanzees and gorillas, so biologically similar to humans, are particularly at risk.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Over the last 35 years, nearly 60% of explained chimp deaths in Uganda's Kibale National Park were from human pathogens, said the science journal.

What is reverse zoonosis?

Human-to-animal disease transmission has been documented on every continent, said Science. This includes Antarctica, where humans and animals are coming into "increasing contact" thanks to research centres and tourism.

Penguins on the "isolated, ice-bound landmass" can pick up a bug from visiting humans, with potentially "devastating consequences" for bird colonies – even extinction.

"[We're] obsessed about the potential for novel diseases to jump from wildlife to humans and cause an epidemic," said ornithologist Kyle Elliott at McGill University in Montreal, Canada. "In reality, the transmission of novel diseases from humans to wildlife has been far more disastrous."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Reverse zoonoses affects species around the world, from "mussels contaminated with hepatitis A virus" to "tigers and mink coming down with Covid-19", said Rachel Nuwer, author of the 2018 book "Poached: Inside the Dark World of Wildlife Trafficking", on Nature.

But because of their evolutionary closeness to humans, sharing 98% of our genetic material, gorillas and chimpanzees tend to be "most vulnerable to our diseases".

Why are great apes catching diseases from humans?

In 1966 primatologist Jane Goodall famously witnessed a deadly polio epidemic among chimpanzees at Gombe Stream National Park in Tanzania, after an outbreak in a human encampment nearby. The disease killed or paralysed many of the chimps she knew and loved.

"Interaction with tourists and loggers can expose chimpanzees to diseases that they cannot fight, like the common cold or the flu," said the Jane Goodall Institute. Even the Ebola virus is affecting the chimpanzee population.

In 2022, a scientific literature review looked at 97 studies that documented proven reverse zoonoses in wild animals (excluding mosquito-borne diseases like yellow fever, which has killed thousands of primates in America). Of those, 57 involved primates. There was a strong association between human pathogens in animals and the amount of contact with humans, the review found.

The human metapneumovirus (HMPV) typically causes respiratory infections in humans that result in a mild cold. But to our closest primate relatives, who have no immunity or evolved genetic resistance, "these diseases can be deadly", wrote Nuwer.

Respiratory pathogens like HMPV have been "the leading chimp killers for more than 35 years, accounting for almost 59% of deaths from a known cause". But the danger is "hardly studied compared with other conservation issues, and public awareness is likewise scant".

What can be done?

In 2015, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) recommended wearing masks in the presence of great apes, limiting the number of tourists per group to eight, restricting observation time to one hour, and maintaining a distance of seven metres between tourists and the animals.

But visiting YouTubers documenting mountain gorilla tourism weren't following these guidelines, according to a study published in 2020. About 40% of social media videos the study analysed showed humans getting within a metre of gorillas.

It's not surprising that 82% of the infected primate populations were either in captivity, or "close proximity to tourists", said El País. "The fact that people are willing to pay $1,000 in Rwanda to see gorillas in the wild speaks volumes."

These studies are a "cautionary reminder" that ecotourism that promotes conservation efforts can be a "double-edged sword". But improving conservation efforts bring "hope through small victories", said the Spanish news site. "As our understanding and awareness of these issues grow, it is likely that outbreaks will become less frequent over time."

Harriet Marsden is a senior staff writer and podcast panellist for The Week, covering world news and writing the weekly Global Digest newsletter. Before joining the site in 2023, she was a freelance journalist for seven years, working for The Guardian, The Times and The Independent among others, and regularly appearing on radio shows. In 2021, she was awarded the “journalist-at-large” fellowship by the Local Trust charity, and spent a year travelling independently to some of England’s most deprived areas to write about community activism. She has a master’s in international journalism from City University, and has also worked in Bolivia, Colombia and Spain.

-

‘The West needs people’

‘The West needs people’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Filing statuses: What they are and how to choose one for your taxes

Filing statuses: What they are and how to choose one for your taxesThe Explainer Your status will determine how much you pay, plus the tax credits and deductions you can claim

-

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency – an ‘engrossing’ exhibition

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency – an ‘engrossing’ exhibitionThe Week Recommends All 126 images from the American photographer’s ‘influential’ photobook have come to the UK for the first time

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire

-

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by Russia

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by RussiaSpeed Read The ship was one of two vessels seized by the US military