It's not just ice quantity that climate change affects. It's also quality.

Ice is getting thinner and frailer

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

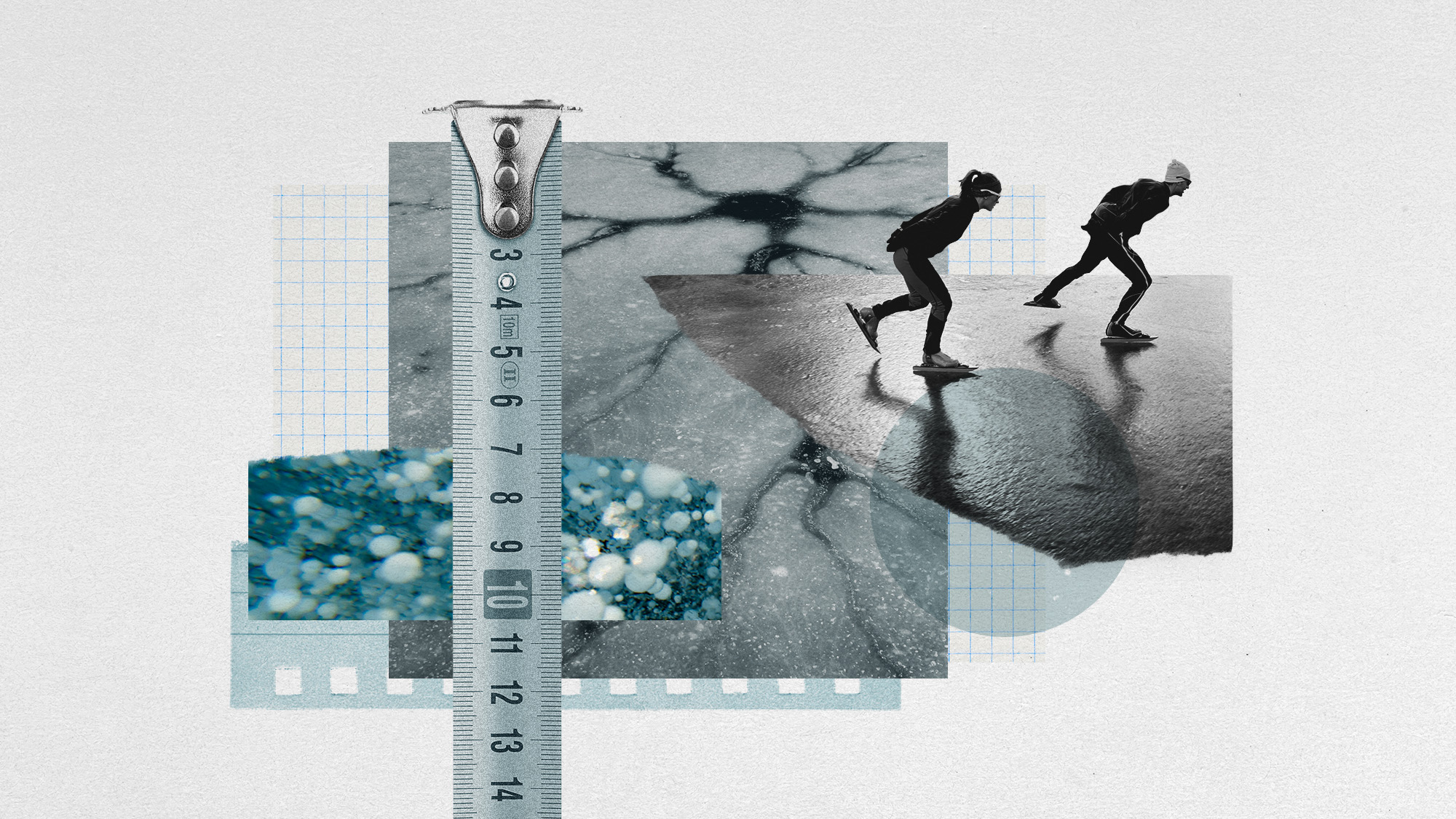

Our days of ice skating or playing hockey on a frozen lake may soon be coming to an end. As climate change worsens and rising temperatures reduce the amount of ice around the world, new research finds that ice quality — which includes its ability to bear weight — has also been affected. This could mean a larger loss of winter sports, as the necessary amounts of snow and ice grow increasingly scarce.

On thin ice

Warming global temperatures due to climate change have caused lake ice to "reduce bearing strength, implying more dangerous conditions for transportation (limiting operational use of many winter roads) and recreation (increasing the risk of fatal spring-time drownings)," said a new study published in the journal Nature Reviews Earth & Environment. The reduced strength is due to a reduction in the quality of the ice rather than the amount. "Ice quality is important because of its direct implications for load bearing capacity for human safety and also how much light will transmit under ice for life under frozen lakes," Sapna Sharma, a professor at York University who worked on the study, said in a press release.

A frozen lake consists of two kinds of ice: white ice and black ice. "White ice is generally opaque, like snow, and filled with more air bubbles and smaller ice crystals, diminishing its strength and stability," said the press release. On the other hand, "black ice is clear and dense with few air pockets and larger ice crystals making it a lot stronger." Warmer winters are "creating thinner layers of black ice and sometimes a corresponding thicker layer of white ice," which can "make for treacherous conditions for skaters, hockey players, snowmobilers, ice anglers and ice truckers." Humans require approximately 10cm or four inches of black ice to stand on the surface safely. A transport truck requires 100cm or about 42 inches of black ice.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Recreation is not the only thing that will be sacrificed with weak ice. The lack of transport trucks can limit communities' access to supplies, and the marine life beneath the ice is also at risk. Increased levels of white ice decrease the "amount of nutrients available for fish and other aquatic life," because white ice can block light from reaching the water, said the release. Without light, phytoplankton and other organisms are unable to perform photosynthesis.

Melting prospects

Many popular winter pastimes are now at risk, including skiing and snowboarding. "Global warming is altering, and endangering" these sports, "perhaps permanently, and not just at the elite level," said The Associated Press. "It affects folks who just want to ski or snowboard for fun and those who make a living from places offering such activities." An increasing number of people have to rely on indoor venues, and some resorts require fake snow to keep business going.

Recreation is ultimately the least of our worries. "I'm worried about my sport's future but, really way beyond that, just worried about our all our futures and how much time we have before it all truly catches up with us," Olympic Alpine skiing champion Mikaela Shiffrin said to the AP. In early 2024, the country "crossed a threshold in which we are at a historic low for ice cover for the Great Lakes as a whole," said Bryan Mroczka, a physical scientist at the U.S. Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory. "We have never seen ice levels this low in mid-February on the lakes since our records began in 1973."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Devika Rao has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022, covering science, the environment, climate and business. She previously worked as a policy associate for a nonprofit organization advocating for environmental action from a business perspective.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warming

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warmingThe explainer It may become impossible to fix

-

The environmental cost of GLP-1s

The environmental cost of GLP-1sThe explainer Producing the drugs is a dirty process

-

The plan to wall off the ‘Doomsday’ glacier

The plan to wall off the ‘Doomsday’ glacierUnder the Radar Massive barrier could ‘slow the rate of ice loss’ from Thwaites Glacier, whose total collapse would have devastating consequences

-

Can the UK take any more rain?

Can the UK take any more rain?Today’s Big Question An Atlantic jet stream is ‘stuck’ over British skies, leading to ‘biblical’ downpours and more than 40 consecutive days of rain in some areas

-

As temperatures rise, US incomes fall

As temperatures rise, US incomes fallUnder the radar Elevated temperatures are capable of affecting the entire economy

-

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’The explainer Water might soon be more valuable than gold

-

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’Under the radar The gender gap has hit the animal kingdom

-

Why scientists want to create self-fertilizing crops

Why scientists want to create self-fertilizing cropsUnder the radar Nutrients without the negatives