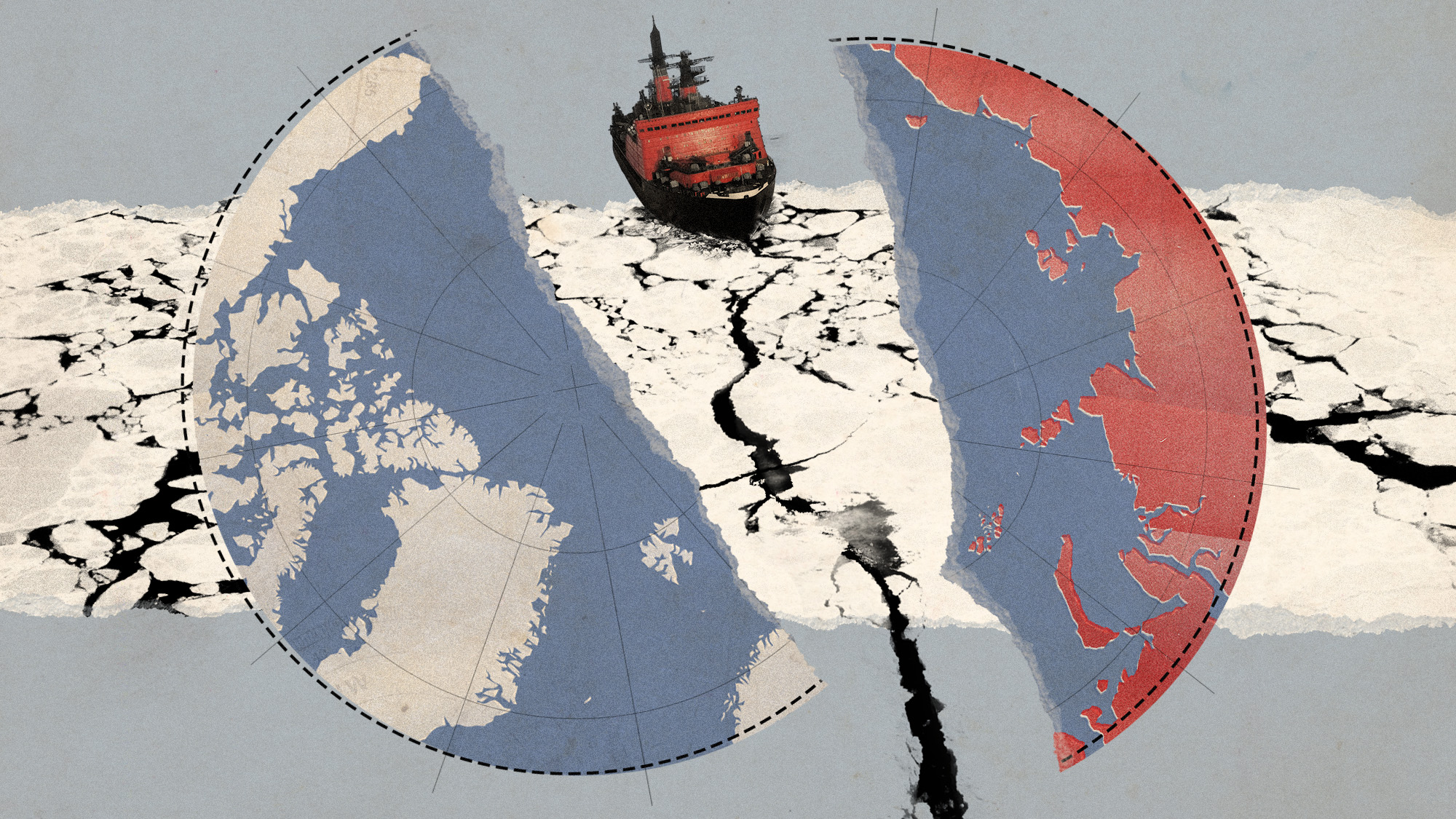

How the war in Ukraine is affecting climate science in the Arctic

Russia's military and strategic ambitions are hampering international efforts to study melting ice

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Russia's ongoing war with Ukraine is having a profound effect on scientists trying to understand how global warming is impacting the North Pole.

Since Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, the Arctic Council, an "intergovernmental forum designed to coordinate activities and research" in the area, has been operating "without the input of Russia", said Newsweek. Given that more than 50% of the Arctic Ocean's coastline is Russian territory, it means the other nations' environmental scientists have been working with "missing data" from the Russian section, "hampering a balanced analysis of climate change".

Studying the Arctic Ocean is "crucially important" to researchers as the area is "warming at between two to four times the average global rate".

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Increasingly inaccurate forecasts

After the outbreak of war, the Arctic Council – consisting of the US, Canada, Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Iceland and Russia – paused its operations. Since resuming, the "western members have rightly refused a business-as-usual approach with Moscow", said The Guardian in an editorial. But the decision has led to huge gaps in data, including "basic measurements of temperature and snowfall" in the Russian Arctic, said NPR, as well as more "sophisticated details" about the area's ecosystem.

This could have a significant impact on the ability to predict the effects of climate change in the future. Modelling forecasts will become "increasingly inaccurate" the longer the data is unavailable. Scientists are also unable to access field sites in Russian territory, instead having "to rely on what they can see from space" to assess environmental changes.

But the thawing ice of the Arctic Circle is also opening up the possibility of accessing the abundance of fossil fuels and minerals beneath the surface, which are now "being sucked into the fallout of Putin’s war", added The Guardian. For the sanctions-hit Kremlin, the "alarming pace of global heating" in the Arctic is now being seen as "an economic opportunity in tough times".

'Putting profit over environmental security'

Though Russia has "long laid a special claim to the Arctic", it has generally remained a cooperative partner in the area's neutrality, said Catherine Philp in The Times. The former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev coined the phrase "Arctic exceptionalism" to refer to it as an "anomalous place immune to many of the world's geopolitical problems".

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But any peaceful cooperation is melting away faster than the ice. The Kremlin has already outlined "national objectives" given the decaying relations, including the "reactivation of dozens of abandoned Cold War military bases". It means Russia "now operates a third more Arctic military bases than the US and Nato combined", said CBS News, and the combination of militarisation and global warming is making the area a "potential military flashpoint".

Russia has "found an ally in China for its Arctic ambitions", said Philp. It is aiming to "open the Northern Sea Route year round" and create a direct route from China to Europe, dubbed the "Polar Silk Road".

But the shipping route shows Russia is "putting profit over environmental security", said the Financial Times, and the northern waters of the Arctic Ocean are becoming "contested maritime environments – commercially, politically and increasingly militarily".

The idea of a Sino-Russian strategy competing with Nato objectives is a "deeply alarming prospect" and could make the region a "new theatre of great-power rivalry", concluded The Guardian. The Arctic has "entered a zone of dangerous geopolitical uncertainty".

Richard Windsor is a freelance writer for The Week Digital. He began his journalism career writing about politics and sport while studying at the University of Southampton. He then worked across various football publications before specialising in cycling for almost nine years, covering major races including the Tour de France and interviewing some of the sport’s top riders. He led Cycling Weekly’s digital platforms as editor for seven of those years, helping to transform the publication into the UK’s largest cycling website. He now works as a freelance writer, editor and consultant.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warming

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warmingThe explainer It may become impossible to fix

-

The plan to wall off the ‘Doomsday’ glacier

The plan to wall off the ‘Doomsday’ glacierUnder the Radar Massive barrier could ‘slow the rate of ice loss’ from Thwaites Glacier, whose total collapse would have devastating consequences

-

Can the UK take any more rain?

Can the UK take any more rain?Today’s Big Question An Atlantic jet stream is ‘stuck’ over British skies, leading to ‘biblical’ downpours and more than 40 consecutive days of rain in some areas

-

As temperatures rise, US incomes fall

As temperatures rise, US incomes fallUnder the radar Elevated temperatures are capable of affecting the entire economy

-

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’The explainer Water might soon be more valuable than gold

-

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’Under the radar The gender gap has hit the animal kingdom

-

Why scientists want to create self-fertilizing crops

Why scientists want to create self-fertilizing cropsUnder the radar Nutrients without the negatives

-

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.Under the radar It is quickly melting away