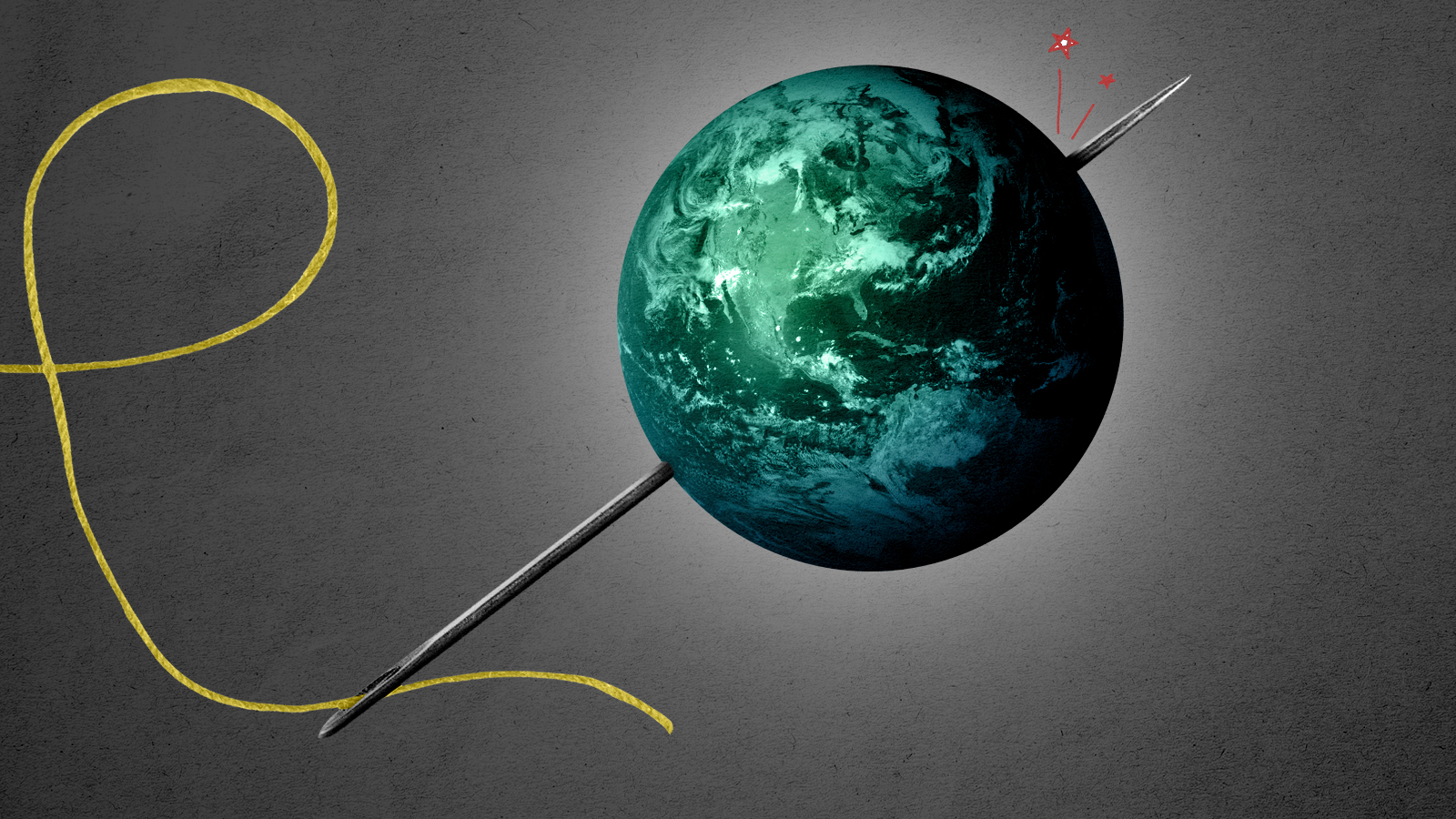

The real cost of fast fashion

Buying cheap clothing has never been easier. But is there a greater price to pay?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The culture around fashion has transformed with the rise of social media, prompting many to buy new clothes often and for cheap. The problem is that we pay for these clothes in different ways, some of which are more detrimental than we realize. Here's everything you need to know about the concerning rise of fast fashion:

What is fast fashion?

Fast fashion refers to clothes that are designed quickly and cheaply to keep up with trends. Many of the most popular and readily accessible brands are fast fashion, including Zara, Forever 21, H&M, and Shein.

Historically, a trend cycle used to last approximately 20 years — meaning that in-fashion looks loop back around every two decades or so, reports NPR. The fashion life cycle rotates through five stages: introduction, increase, peak, decline, and obsolescence.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

However, due to the rise of social media, and especially Tiktok, trends are starting to resurface faster in addition to dying faster. This is because social media encourages "microtrends," which are when an article or a particular piece of clothing becomes trendy rather than a larger genre, but then just as quickly falls out of fashion. This causes companies to quickly design and produce new pieces, just for them to soon become obsolete. Now, microtrends that used to last three to five years only last a few months.

The accelerated fashion life cycle has put pressure both on the environment as well as laborers who have to bear the brunt of the production turnarounds.

How does fast fashion impact the environment?

According to the UN Environment Programme, the fashion industry is the second highest for water consumption and makes up approximately eight 8 to 10 percent of global carbon emissions. Fashion production tends to average a 5 percent increase per year — however, even that much is likely to be detrimental in the future, Bloomberg reports. Without action, emissions from textile production will increase by 100 million tons, or 60 percent, by 2030. This will also place "an unprecedented strain on planetary resources," Euromonitor analysts say.

Clothing production is already at an all-time high. For example, the brand Zara and its affiliated brands produce over 840 million garments a year and that number is steadily growing. In an interview with The New York Times, Amancio Ortega Gaona, founder of Zara, said, "With Zara, you know that if you don't buy it right then and there, within 11 days the entire stock will change. You buy it now or never. And because the prices are so low, you buy it now."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

More recently, online retailer Shein has become one of the most popular cheap clothing brands. The Chinese company has a network of contract manufacturers allowing them to quickly pump out thousands of garments for some of the lowest prices you can find, reports Bloomberg. The company made $16 billion in sales in 2021, making it one of the world's top startups and catapulting it into popularity in the fashion scene. The company has also received lots of complaints regarding its environmental impact and working conditions.

Tiktok has played a large part in Shein and other fast fashion brands' success. "Haul" videos are incredibly popular, which depict people showing off the number of new pieces they were able to buy for a few hundred dollars. Most of those pieces, being trendy pieces, will likely fall out of fashion quickly, though. Along with trends going out of style quickly, fast fashion companies also tend to sacrifice quality for inventory, churning out as many garments as possible, but without longevity for the pieces.

This leads to the other major outcome of fast fashion: the majority of the clothing ending up in landfills. Currently, approximately 85 percent of textiles are discarded in the U.S., according to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Only about 13 percent of clothing and shoes are recycled. Globally, we are expected to discard more than 134 million tonnes of textiles annually by 2030. In order to combat this, many companies are creating recycling programs or opting to use recycled fabrics; however, much more needs to be done to create substantial results in environmental harm reduction.

What is the human cost of fast fashion?

Fashion has also caused ethical problems in developing nations. For example, U.S. textile waste has created a "salvage market" in recipient Ghana, reports CBS News. Much of this clothing actually comes from American donation centers because some of the donated clothes are of poor quality and cannot be resold. The unusable clothing, however, is polluting Ghanian marketplaces, beaches, and dumps.

Along with the environmental impacts, fast fashion has also caused a spike in questionable labor practices. There have been reports of popular fast fashion brands using sweatshops and even child labor to be able to hit the levels of production that they do.

Sweatshops don't just exist in developing nations. In 2019, Fashion Nova, another online fast fashion retailer like Shein, was exposed for exploiting and underpaying its workers in Los Angeles sweatshops. A number of other brands, including Forever 21, Ross, and TJ Maxx have also faced complaints of worker exploitation as the Los Angeles Times reports.

Much of the child labor in the industry comes during the process of obtaining raw materials, like cotton. Southern India has a history of having children create yarn; however, the industry has made strides to eradicate it. Benin, Uzbekistan, and Bangladesh have also taken part in child labor for the textile industry.

What can consumers do?

The best thing consumers can do is aim for sustainability. Looking at second-hand options like thrift stores or clothing swaps will also reduce the demand for clothing production.

When shopping, seek brands that are provably ethical and sustainable (Good On You is a great resource for finding out which brands actually walk the walk in addition to talking the talk). Likewise, don't be afraid to be an #OutfitRepeater and opt to shop instead for durable and timeless pieces that can be worn for years.

Devika Rao has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022, covering science, the environment, climate and business. She previously worked as a policy associate for a nonprofit organization advocating for environmental action from a business perspective.

-

Political cartoons for February 19

Political cartoons for February 19Cartoons Thursday’s political cartoons include a suspicious package, a piece of the cake, and more

-

The Gallivant: style and charm steps from Camber Sands

The Gallivant: style and charm steps from Camber SandsThe Week Recommends Nestled behind the dunes, this luxury hotel is a great place to hunker down and get cosy

-

The President’s Cake: ‘sweet tragedy’ about a little girl on a baking mission in Iraq

The President’s Cake: ‘sweet tragedy’ about a little girl on a baking mission in IraqThe Week Recommends Charming debut from Hasan Hadi is filled with ‘vivid characters’

-

Ski town strikers fight rising cost of living

Ski town strikers fight rising cost of livingThe Explainer Telluride is the latest ski resort experiencing a patroller strike

-

What will the US economy look like in 2026?

What will the US economy look like in 2026?Today’s Big Question Wall Street is bullish, but uncertain

-

Starbucks workers are planning their ‘biggest strike’ ever

Starbucks workers are planning their ‘biggest strike’ everThe Explainer The union said 92% of its members voted to strike

-

Labor: Federal unions struggle to survive Trump

Labor: Federal unions struggle to survive TrumpFeature Trump moves to strip union rights from federal workers

-

Jared and Ivanka's Albanian island

Jared and Ivanka's Albanian islandUnder The Radar The deal to develop Sazan has been met with widespread opposition

-

Airport expansion: is Labour choosing growth over the environment?

Airport expansion: is Labour choosing growth over the environment?Today's Big Question Government indicates support for third Heathrow runway and expansion of Gatwick and Luton, despite climate concerns

-

US port strike averted with tentative labor deal

US port strike averted with tentative labor dealSpeed Read The strike could have shut down major ports from Texas to Maine

-

Christmas trees: losing their magic?

Christmas trees: losing their magic?In the Spotlight Festive firs are a yuletide staple but are their days numbered?