The fast-paced world of speedcubing

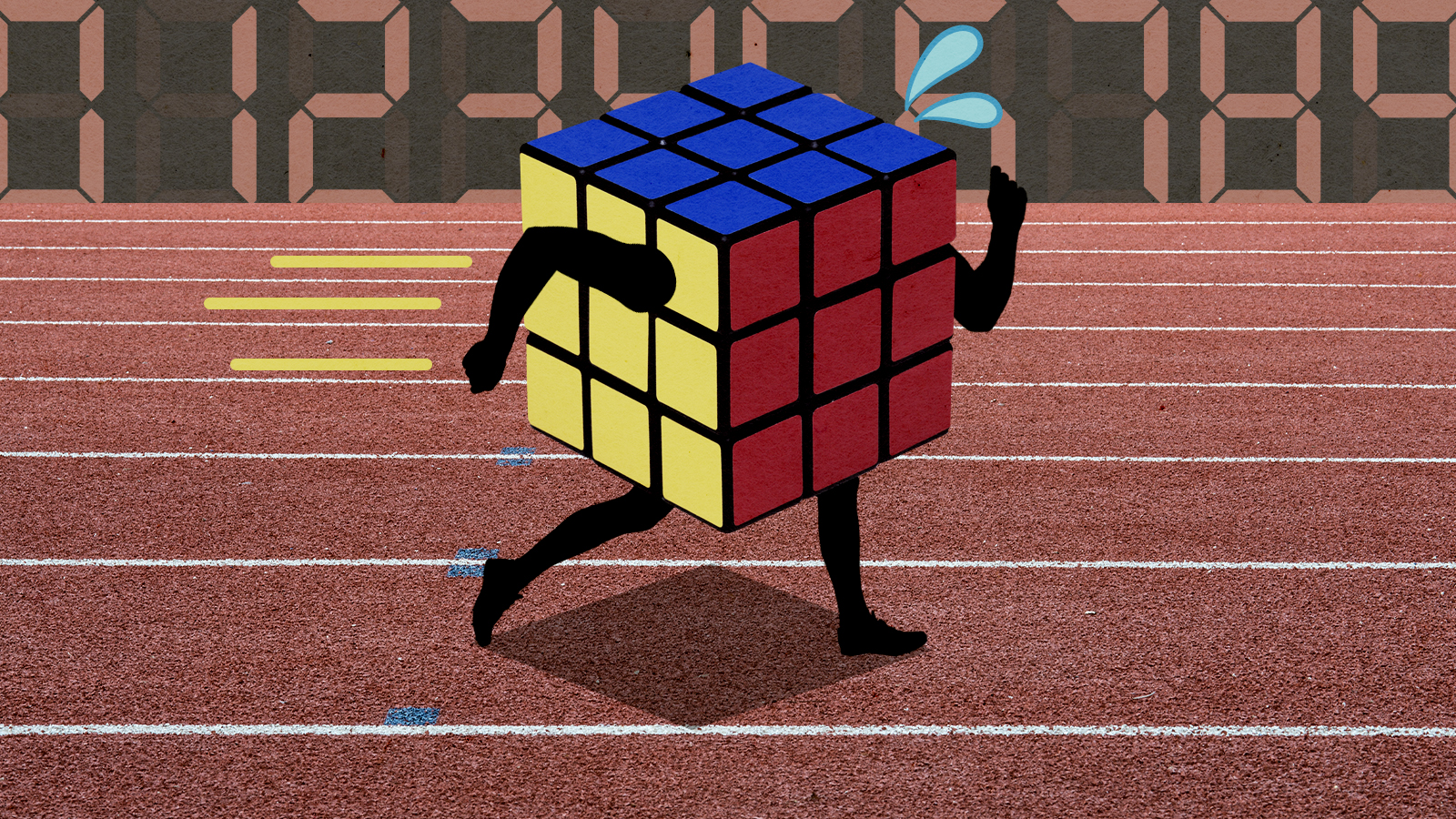

How a six-color block puzzle has sparked global competition

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Since its invention in 1974, the Rubik's cube has taken the world and its hobbyists by storm. But the brightly-colored block puzzle has also fostered some fierce competition, as global puzzle fanatics put their algorithmic understanding and finger dexterity to the ultimate test. Welcome to the world of speedcubing — here's everything you need to know:

First and foremost — where did the Rubik's Cube come from?

The Rubik's Cube was first invented by Hungarian architecture professor Ernő Rubik to model 3D movement for his students. The original version, called the "magic cube," was made of wood and paper and held together with rubber bands, glue, and paper clips.

Now, the puzzle is one of the most iconic toys in human history, with over 350 million sold as of 2018. Though the cube looks approachable, it's deceptively difficult to solve — there are over 43 quintillion ways of scrambling it. Even Rubik himself took a month to solve the puzzle for the first time, noting that he felt "a great sense of accomplishment and utter relief" once he did.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The solution process is also incredibly algorithmic, to the point where Pulitzer-Prize-winning scientist Douglas Hofstadter has called the cube "one of the most amazing things ever invented for teaching mathematical ideas."

What is speedcubing and how did it start?

Eventually, the Rubik's cube sparked a worldwide phenomenon known as speedcubing, in which individuals compete to solve the cube as fast as possible. The challenge has since moved past the classic 3x3x3 cube and evolved in ways that have pushed the boundaries of what is mathematically and physically possible.

The first official speedcubing world championship took place on June 5, 1982, in Budapest, Hungary, where American Minh Thai won with a solve time of 22.95 seconds. His is regarded as the first official world record relating to the Rubik's Cube.

Shortly after, however, speedcubing in a competitive sense took a hiatus. Even The New York Times deemed the cube a "fad" that had "become passe." But the movement picked up again in the 1990s with the advent of the internet, where online speedcubing groups and games were launched.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The Yahoo! Speedsolving Rubik's Cube Group — where people discussed tactics and compared times — then started in 2000, with speedcubing.com, which unofficially tracked major cubing news and time records, arriving shortly thereafter. In 2004, the World Cube Association (WCA) was formed and competitions were held more regularly.

What is the World Cube Association?

The WCA is the governing body for cubing competitions, which includes those related to the Rubik's Cube as well as other twist-to-solve puzzles. The WCA hosts over 1,000 speedcubing competitions annually and a world championship every two years.

The body standardized competitive speedcubing by releasing rules and regulations, centralizing records and information, and setting up a system for people to host valid competitions for speedcubing. Over 140,000 cubers from 143 countries are officially registered with the WCA.

What do cubing competitions look like?

The first official WCA speedcubing competition was held in Kyoto, Japan, in 2005. But what does a competition look like?

A speedcubing competition can have between one and 18 events and tends to have multiple rounds for each event. Competitors are split into groups and set up with a so-called stackmat timer, which is used to time attempts and keep the cube from sliding once the attempt is complete. All competitors participate in the first round and those who qualify will participate in subsequent rounds.

The scrambled puzzle is kept covered until the start of the run, when the participant has 15 seconds to examine the cube before officially starting their attempt. The cubes are computer scrambled in the exact same way for every competitor so as to standardize the competition.

After inspecting their cube, the competitor then puts it down and places both their hands on the stackmat before getting the signal to begin solving. Scoring can occur in different ways depending on the competition — some competitions take an average of multiple attempts and some take the best time. China's Yusheng Du holds the current world record — 3.47 seconds — for solving a 3x3x3 cube.

Over the years, the competition has greatly expanded to include 4x4x4, 5x5x5, 6x6x6, and 7x7x7 puzzles, as well as categories where contestants solve the cube while blindfolded or with one hand.

More than a cube?

The impact of the cube has been far greater than even the now 78-year-old Rubik could have imagined. He attempted to parse that legacy in his book Cubed, published in 2020. "I don't want to write an autobiography, because I am not interested in my life or sharing my life," Rubik told The New York Times at the time. "The key reason I did it is to try to understand what's happened and why it has happened. What is the real nature of the cube?"

But as he wrote Cubed, "I changed my mind," Rubik remarked. "What really interested me was not the nature of the cube, but the nature of people, the relationship between people and the cube."

Devika Rao has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022, covering science, the environment, climate and business. She previously worked as a policy associate for a nonprofit organization advocating for environmental action from a business perspective.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The best family board games

The best family board gamesThe Week Recommends Put down the smartphones and settle in for some old fashioned fun

-

Down with Uno, up with this exciting collection of one-of-a-kind travel games

Down with Uno, up with this exciting collection of one-of-a-kind travel gamesThe Week Recommends Game on!

-

Roblox: new safety features leave kids 'at risk'

Roblox: new safety features leave kids 'at risk'The Explainer Gaming platform loved by children has been plagued by explicit content and grooming

-

Chess on TV: a winning strategy?

Chess on TV: a winning strategy?Talking Point The popularity of chess is surging, but a new reality TV show struggles to capitalise on the craze

-

Cozy video games to help you unwind from the chaos

Cozy video games to help you unwind from the chaosThe Week Recommends Some games can go a long way in alleviating stress or anxiety

-

A popular new video game is at the center of China's censorship dispute

A popular new video game is at the center of China's censorship disputeIn the Spotlight 'Black Myth: Wukong' has more than a million players, but some are criticizing China's oversight of the game

-

The video game franchises with the best lore

The video game franchises with the best loreThe Week Recommends The developers behind these games used their keen attention to detail and expert storytelling abilities to create entire universes

-

The buzziest movies from the 2023 Venice Film Festival

The buzziest movies from the 2023 Venice Film FestivalSpeed Read Which would-be Oscar contenders got a boost?