A flesh-eating bacteria is growing in numbers due to climate change

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

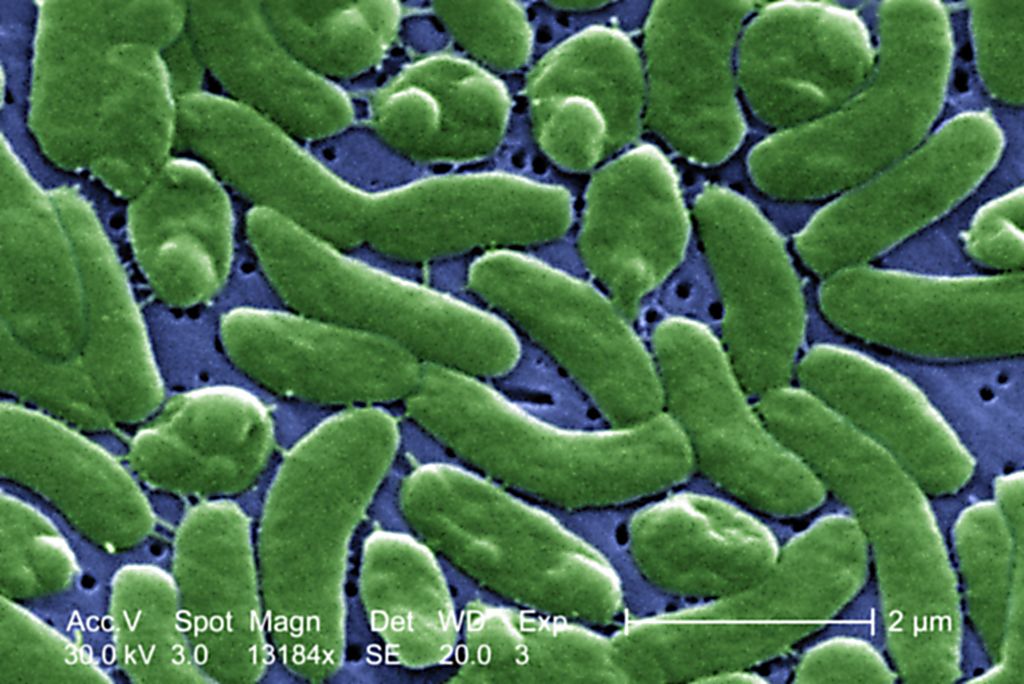

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has released a health alert to healthcare providers to look out for infections of the "flesh-eating" bacteria known as Vibrio vulnificus. The bacteria is deadly and can be contracted by "eating raw or undercooked shellfish, particularly oysters," or "when an open wound is exposed to salt water or brackish water" that contains Vibrio, the alert said. The bacteria is naturally found in coastal waters.

The bacteria usually affects 150 to 200 per year and about one in five die from infection. Just this year, the bacteria has caused at least 12 deaths, Axios reported. Numbers have also been on the rise as temperatures have been rising.

"V. vulnificus is only active at a temperature that's above 13 degrees Celsius, and then it becomes more prevalent up until the temperature reaches 30 degrees Celsius, which is 86 Fahrenheit," Karen Knee, an associate professor and water-quality expert at American University, told Wired. Oceans have been reaching record-high temperatures, thus worsening the bacteria's presence. "The warmer water is, the more bacteria can reproduce faster," Gabby Barbarite, a researcher at Florida Atlantic University's Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute, told USA Today.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Though deemed a "flesh-eating" bacteria, the infection kills tissue but doesn't eat it. In order to be infected, the bacteria must enter the body through food or a break in the skin, explained USA Today. Infection can cause, diarrhea, stomach cramping, nausea, vomiting, fever, and chills and can usually be cured with antibiotics. One species of Vibrio, however, can lead to a life-threatening infection and can cause death within two days. "All these changes in climate that we are seeing, including the tremendous heating of the oceans, is making the geography of infectious diseases change," Cesar Arias, a professor and chief of infectious diseases at Houston Methodist Hospital, told Wired.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Devika Rao has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022, covering science, the environment, climate and business. She previously worked as a policy associate for a nonprofit organization advocating for environmental action from a business perspective.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Scientists are worried about amoebas

Scientists are worried about amoebasUnder the radar Small and very mighty

-

Metal-based compounds may be the future of antibiotics

Metal-based compounds may be the future of antibioticsUnder the radar Robots can help develop them

-

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillance

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillanceUnder the radar The disease can spread through animals and humans

-

Trump HHS slashes advised child vaccinations

Trump HHS slashes advised child vaccinationsSpeed Read In a widely condemned move, the CDC will now recommend that children get vaccinated against 11 communicable diseases, not 17

-

Deaths of children under 5 have gone up for the first time this century

Deaths of children under 5 have gone up for the first time this centuryUnder the radar Poor funding is the culprit

-

A fentanyl vaccine may be on the horizon

A fentanyl vaccine may be on the horizonUnder the radar Taking a serious jab at the opioid epidemic

-

Health: Will Kennedy dismantle U.S. immunization policy?

Health: Will Kennedy dismantle U.S. immunization policy?Feature ‘America’s vaccine playbook is being rewritten by people who don’t believe in them’

-

More adults are dying before the age of 65

More adults are dying before the age of 65Under the radar The phenomenon is more pronounced in Black and low-income populations