Monkeypox comes to America

What to know about the latest virus of concern

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The first U.S. monkeypox case of the year has been detected in Massachusetts — a cause for some minor alarm because it comes on the heels of a rare worldwide outbreak of the disease. As of Thursday morning, 68 cases have reportedly been detected in England, Spain, Portugal, and Canada.

"This is rare and unusual," said Dr. Susan Hopkins, chief medical adviser to the U.K. Health Security Agency. Authorities are "rapidly investigating the source of these infections because the evidence suggests that there may be transmission of the monkeypox virus in the community, spread by close contact."

Is it time to worry about another rare virus, and what's the best way to protect against it?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What is monkeypox?

"Monkeypox is a more benign version of the smallpox virus and can be treated with an antiviral drug developed for smallpox," Apoorva Mandavilli reports in the New York Times. "But unlike measles, COVID, or influenza, monkeypox does not typically cause large outbreaks."

It's not fun to experience, though. "Monkeypox can be a nasty illness; it causes fever, body aches, enlarged lymph nodes, and eventually 'pox,' or painful, fluid-filled blisters on the face, hands, and feet," Michaeleen Doucleff writes at NPR. "One version of monkeypox is quite deadly and kills up to 10 percent of people infected." If that sounds terrifying, there's some bit of good news: "The version currently in England is milder. Its fatality rate is less than 1 percent."

Some signs to watch: "Early symptoms of monkeypox include fever, headache, muscle aches, swollen lymph nodes, and chills," Sam Jones says in The Guardian. "A rash that can look like chickenpox or syphilis can also develop and spread from the face to other parts of the body, including the genitals. Most people recover within a few weeks."

How is it transmitted?

The virus "occurs primarily in tropical rainforest areas of Central and West Africa and is occasionally exported to other regions," the World Health Organization reports in an overview. "Monkeypox virus is mostly transmitted to people from wild animals such as rodents and primates, but human-to-human transmission also occurs." When that happens, an infected person can pass along the virus "via respiratory droplets — virus-laced saliva that can infect the mucosal membranes of the eyes, nose, and throat — or by contact with monkeypox lesions or bodily fluids, with the virus entering through small cuts in the skin," Helen Branswell says at STAT. "It can also be transmitted by contact with clothing or linens contaminated with material from monkeypox lesions."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Of particular concern: A number of the recent cases have been discovered in gay and bisexual men. "In this event, transmission between sexual partners, due to intimate contact during sex with infectious skin lesions seems the likely mode of transmission," the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control says in its briefing. Usually, the virus has a hard time jumping from one person to the next. "Transmission between humans mostly occurs through large respiratory droplets. As droplets cannot travel far, prolonged face-to-face contact is needed."

Has the U.S. seen an outbreak before?

Yes. The virus appears in the United States in isolated cases from time to time, but there was a significant outbreak in 2003. That year, 47 "confirmed and probable cases of monkeypox were reported from six states — Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Missouri, Ohio, and Wisconsin," the Centers for Disease Control says in its briefing on the topic. "All people infected with monkeypox in this outbreak became ill after having contact with pet prairie dogs. The pets were infected after being housed near imported small mammals from Ghana. This was the first time that human monkeypox was reported outside of Africa."

Is there a vaccine?

The virus is similar to the smallpox virus — and there are smallpox vaccines. "Because monkeypox virus is closely related to the virus that causes smallpox, the smallpox vaccine can protect people from getting monkeypox," the CDC reports. It's best to get the vaccine before exposure, but "experts also believe that vaccination after a monkeypox exposure may help prevent the disease or make it less severe." The good news: "Past data from Africa suggests that the smallpox vaccine is at least 85 percent effective in preventing monkeypox." Indeed, "the U.S. government has ordered millions of doses of a vaccine that protects against monkeypox," Ed Browne writes at Newsweek.

So far, the virus has appeared in only a few dozen people. But the world's recent experience with COVID-19 — which spawned the Delta and Omicron variants — means vigilance is a good idea, Clare Wilson points out in NewScientist. "Any disease that circulates in animals and can be passed to people has potential to cause a new pandemic, if it mutates to become more deadly or more easily transmissible."

Joel Mathis is a writer with 30 years of newspaper and online journalism experience. His work also regularly appears in National Geographic and The Kansas City Star. His awards include best online commentary at the Online News Association and (twice) at the City and Regional Magazine Association.

-

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problem

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problemThe Explainer Before her appointment as cabinet secretary, commentators said hostile briefings and vetting concerns were evidence of ‘sexist, misogynistic culture’ in No. 10

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

5 recent breakthroughs in biology

5 recent breakthroughs in biologyIn depth From ancient bacteria, to modern cures, to future research

-

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkiller

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkillerUnder the radar The process could be a solution to plastic pollution

-

Scientists want to regrow human limbs. Salamanders could lead the way.

Scientists want to regrow human limbs. Salamanders could lead the way.Under the radar Humans may already have the genetic mechanism necessary

-

A potentially mutating bat virus has some scientists worried about the next pandemic

A potentially mutating bat virus has some scientists worried about the next pandemicUnder the Radar One subgroup of bat merbecovirus has scientists concerned

-

Is the world losing scientific innovation?

Is the world losing scientific innovation?Today's big question New research seems to be less exciting

-

Breakthrough gene-editing treatment saves baby

Breakthrough gene-editing treatment saves babyspeed read KJ Muldoon was healed from a rare genetic condition

-

Humans heal much slower than other mammals

Humans heal much slower than other mammalsSpeed Read Slower healing may have been an evolutionary trade-off when we shed fur for sweat glands

-

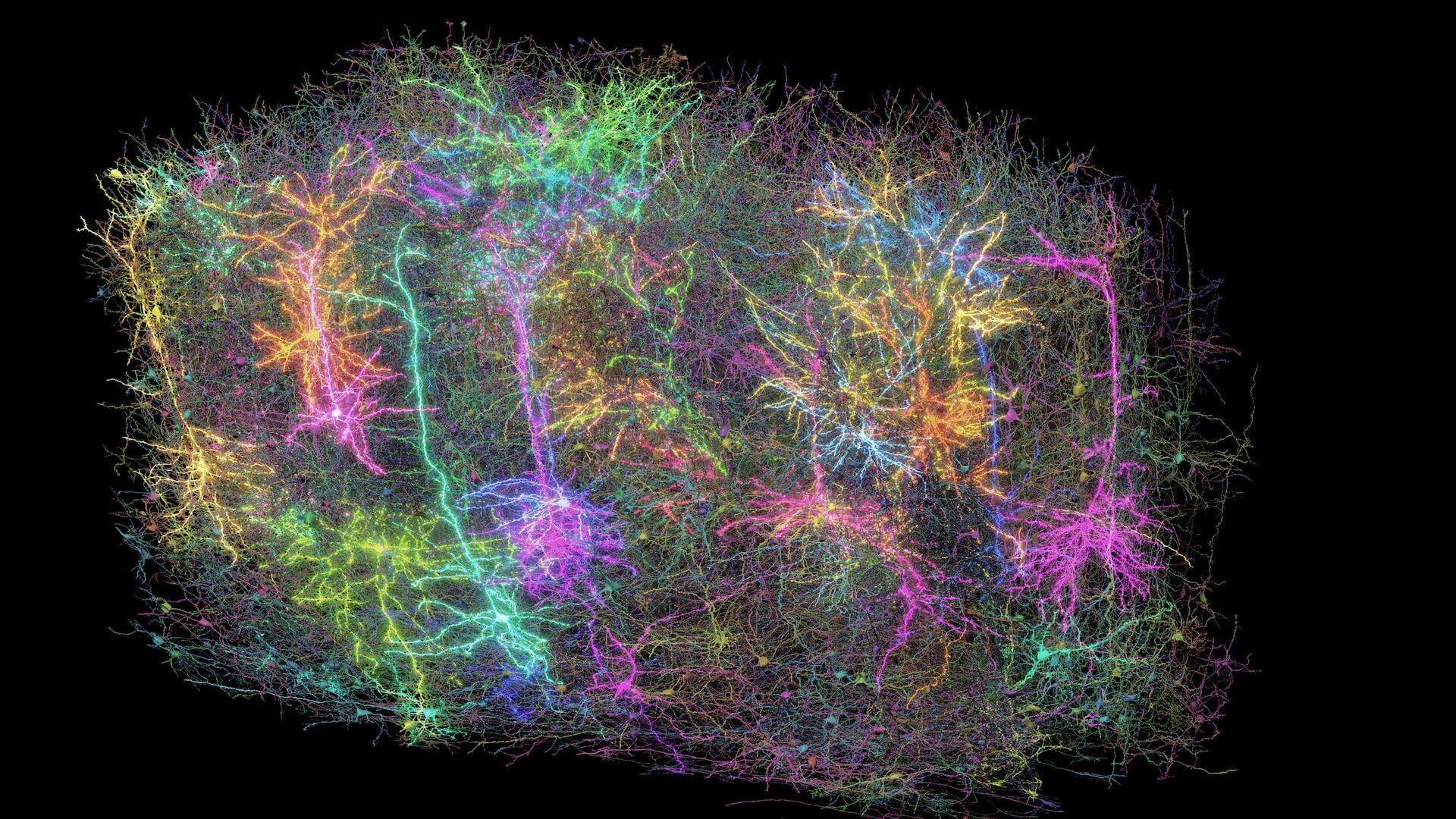

Scientists map miles of wiring in mouse brain

Scientists map miles of wiring in mouse brainSpeed Read Researchers have created the 'largest and most detailed wiring diagram of a mammalian brain to date,' said Nature