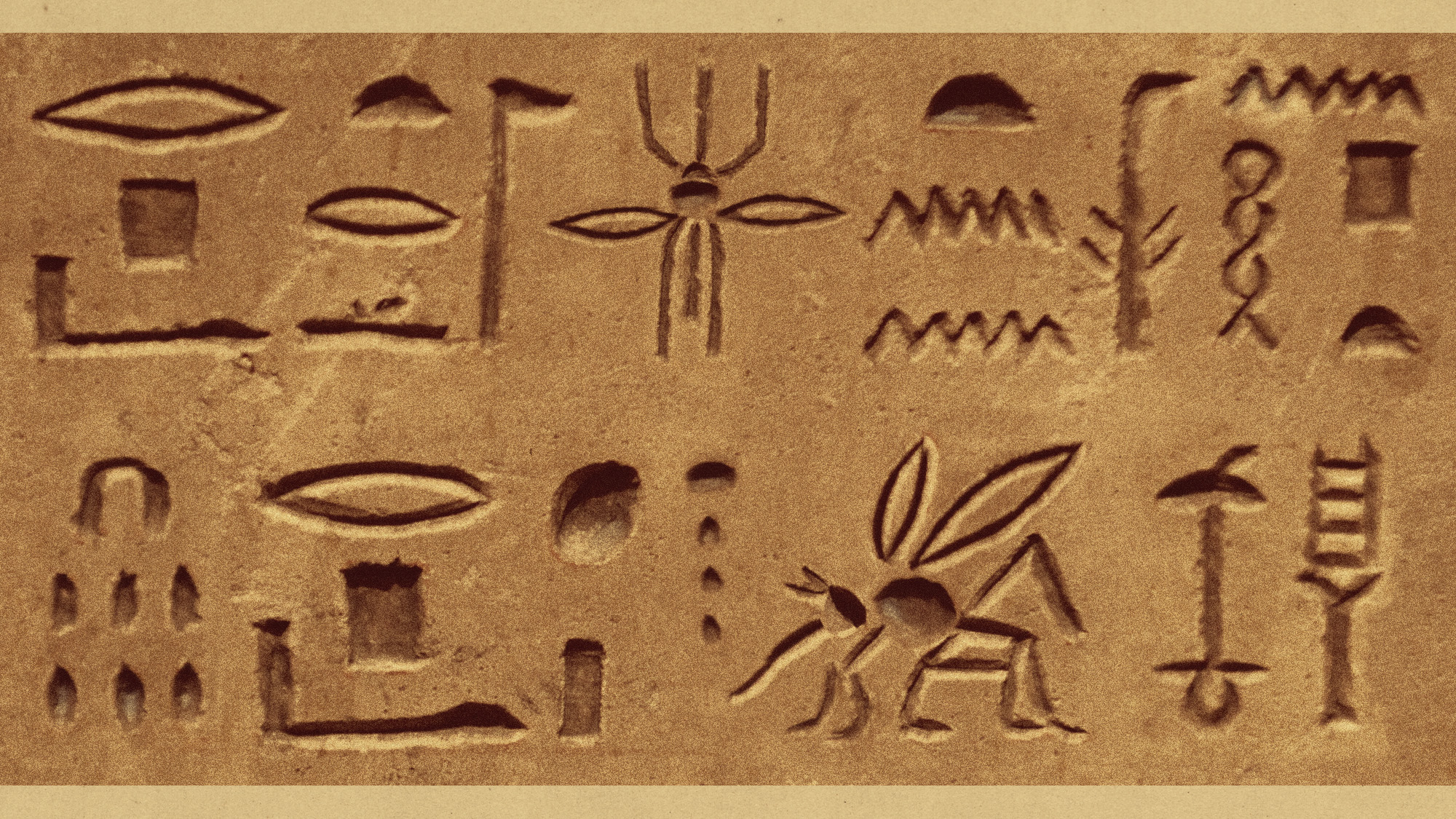

No more bugging: how Egypt became certified malaria-free

It was a century-long effort

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Malaria is a deadly disease caused by a parasite spread by the Anopheles species of mosquito. The condition tends to be more prevalent in warmer regions and those near the equator, including sub-Saharan Africa, parts of Oceania and parts of Central and South America and Southeast Asia. Egypt once had high levels of malaria but was able to curb transmission after a nearly 100-year effort. As a result of the country's work, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared Egypt to be certified malaria-free.

Malaria no more

The WHO only designates a country malaria-free once the country has proven "beyond reasonable doubt, that the chain of indigenous malaria transmission by Anopheles mosquitoes has been interrupted nationwide for at least the previous three consecutive years," and has demonstrated the "capacity to prevent the reestablishment of transmission," said the WHO. The agency to date has only granted the designation to 44 countries and one territory. Egypt is the latest to reach the milestone.

In Egypt, the disease can be traced back as far as 4000 BCE, with evidence of the disease being found in some mummies. The effort to curb the disease took shape in the 1920s when the country prevented the cultivation of rice and other crops near houses. Malaria was designated a notifiable disease in 1930 when prevalence hit 40% and "Egypt later opened its first malaria control station focused on diagnosis, treatment and surveillance," said the WHO.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

World War II, with its resulting population displacement and disruption of medical supplies, along with the completion of the Aswan Dam in 1969, which increased the country's volume of standing water, caused a spike in cases. In response to the malaria uptick, "Egypt, in collaboration with Sudan, launched a rigorous vector control and public health surveillance project to rapidly detect and respond to malaria outbreaks."

Malaria was "firmly under control" by 2001. Throughout Egypt, malaria diagnosis and treatment are free of charge for everyone regardless of legal status, and the country has fostered "strong cross-border partnership with neighboring countries," said the WHO. "Malaria is as old as Egyptian civilization itself, but the disease that plagued pharaohs now belongs to its history," said WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus. "This certification of Egypt as malaria-free is truly historic, and a testament to the commitment of the people and government of Egypt to rid themselves of this ancient scourge."

Disease domination

Malaria kills approximately 600,000 people each year, with most deaths occurring in Sub-Saharan Africa. The disease is most prevalent in tropical and subtropical climates. While vaccines and preventative medicines are available in some parts of the world, "monitoring the disease and avoiding mosquito bites are the most effective ways to prevent malaria," said the BBC. Products like mosquito nets and bug sprays can help prevent mosquito bites and the spread of malaria.

The growing problem is that the range of mosquitos has slowly been increasing due to climate change. Warming temperatures are causing malaria and other mosquito-borne illnesses to spread to regions that may have been safe from the disease before. Egypt's success in limiting malaria showcases how proper government intervention can benefit public health. "Receiving the malaria elimination certificate today is not the end of the journey but the beginning of a new phase," H.E. Dr Khaled Abdel Ghaffar, the Deputy Prime Minister of Egypt, said. "We must now work tirelessly and vigilantly to sustain our achievement through maintaining the highest standards for surveillance, diagnosis and treatment, integrated vector management and sustaining our effective and rapid response to imported cases."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Devika Rao has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022, covering science, the environment, climate and business. She previously worked as a policy associate for a nonprofit organization advocating for environmental action from a business perspective.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Scientists are worried about amoebas

Scientists are worried about amoebasUnder the radar Small and very mighty

-

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deaths

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deathsThe Explainer Holidaymakers sue Tui after gastric illness outbreaks linked to six British deaths

-

Metal-based compounds may be the future of antibiotics

Metal-based compounds may be the future of antibioticsUnder the radar Robots can help develop them

-

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillance

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillanceUnder the radar The disease can spread through animals and humans

-

Is the US about to lose its measles elimination status?

Is the US about to lose its measles elimination status?Today's Big Question Cases are skyrocketing

-

A real head scratcher: how scabies returned to the UK

A real head scratcher: how scabies returned to the UKThe Explainer The ‘Victorian-era’ condition is on the rise in the UK, and experts aren’t sure why

-

Trump HHS slashes advised child vaccinations

Trump HHS slashes advised child vaccinationsSpeed Read In a widely condemned move, the CDC will now recommend that children get vaccinated against 11 communicable diseases, not 17

-

Deaths of children under 5 have gone up for the first time this century

Deaths of children under 5 have gone up for the first time this centuryUnder the radar Poor funding is the culprit