Is violence against politicians getting worse?

Rise in far-right extremism is one factor behind series of attacks on political figures

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A spate of attacks on leading political figures around the world has prompted lawmakers to issue stark warnings about increasing violence and rallying cries for the preservation of democracy.

Following the assault on the husband of US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi last week, President Joe Biden used a prime-time address on Wednesday to highlight growing threats of violence, often from those espousing extremist ideologies, as the country barrels towards its midterm elections next week.

The string of attacks have occurred in disparate parts of the world over the past year, prompting some analysts to question whether a trend is emerging.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What has happened?

Pakistan’s former prime minister Imran Khan survived a shooting at a political rally this week that his party called an assassination attempt.

The Ministry of Information in Islamabad released a video of a confession from an unnamed man who said he “wanted to kill Imran Khan” because he “was misleading people”, adding that he had no accomplices.

It followed an assault last week in San Francisco on Paul Pelosi, the husband of leading Democrat Nancy Pelosi.

Paul Pelosi was attacked on 28 October by a man who broke into the couple’s house in the middle of the night and attacked him with a hammer. David DePape, 42, was charged with assault and attempted murder, and also the attempted kidnapping of Nancy Pelosi, who wasn’t home at the time.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

DePape told police that he was intending to “interview” Pelosi. If she told the “truth” he would let her go, but if she “lied” he planned to “break her kneecaps”, forcing her to be wheeled into Congress as a lesson to other Democrats.

Earlier this year, Shinzo Abe, prime minister of Japan until 2020, was assassinated while he was speaking at a political event in Nara City. The suspect, 41-year-old Tetsuya Yamagami, was arrested at the scene. Yamagami confessed to investigators that he had shot Abe because of a grudge he held against the Unification Church, to which Abe and his family had political ties.

On 15 October last year, British MP David Amess was fatally stabbed at his Essex constituency surgery by Ali Harbi Ali. The 26-year-old had travelled from London to Leigh-On-Sea armed with a large kitchen knife and used a false address to deceive the MP’s staff that he lived in the local area.

Nick Price, head of the CPS counter-terrorism division, said: “Sir David’s murder was a terrible attack on an MP as he went about his work. But it was also an attack on our democracy, it was an attack on all of us, an attack on our way of life.”

What did the papers say?

Violence in Pakistan is nothing new, said Jason Burke in The Guardian. Rather the attack on Khan merely “underlines once again how politics in Pakistan is inseparable from violence”.

Yet while political violence may be the norm in Pakistan, some other recent attacks – including that on Abe in Japan and MPs Amess and Jo Cox in the UK – betray an emerging trend, said the Australian National University’s Dr William Stoltz in the Australian newspaper the Herald Sun. Japan’s experience, for example, offers a “stark warning” to democracies that value “peaceful traditions of open and accessible relationships between public officials and their constituents”.

According to experts who study extremism, the rise in political violence in the US, at least, is largely being driven by the right. A 2020 paper from the Center for Strategic and International Studies found that two-thirds of domestic terrorism from January to August that year was the work of far-right extremists while just one-fifth came from groups on the far left.

“Although incidents from the left are on the rise, political violence still comes overwhelmingly from the right,” the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace’s Rachel Kleinfeld wrote in a research paper on emerging trends in political violence last year.

What next?

What we are witnessing is “all very unpleasant”, said The Spectator in the wake of an attack on the British MP Iain Duncan Smith at the Tory Party conference last year.

And yet “a sense of historical perspective is needed”. Attacks on politicians in Britain, at least, are particularly shocking because the “political scene today is generally so peaceable”.

During the Gordon Riots of 1780, the prime minister Lord North had to be rescued by the military from an angry mob outside Downing Street, the magazine noted. And in 1859, meanwhile, 30,000 Tory supporters swarmed Nottingham and ransacked the Liberal Party’s local office.

It may be true that “violence goes in cycles”, Lilliana Mason, a political science professor at Johns Hopkins University, told Vox. However, “just because patterns of progress and violence exist, that doesn’t mean that they occur naturally”.

Ending such patterns depends on how we “decide to participate in democratic institutions”, Mason said, “or if we can even come to an understanding about what democracy is”.

Arion McNicoll is a freelance writer at The Week Digital and was previously the UK website’s editor. He has also held senior editorial roles at CNN, The Times and The Sunday Times. Along with his writing work, he co-hosts “Today in History with The Retrospectors”, Rethink Audio’s flagship daily podcast, and is a regular panellist (and occasional stand-in host) on “The Week Unwrapped”. He is also a judge for The Publisher Podcast Awards.

-

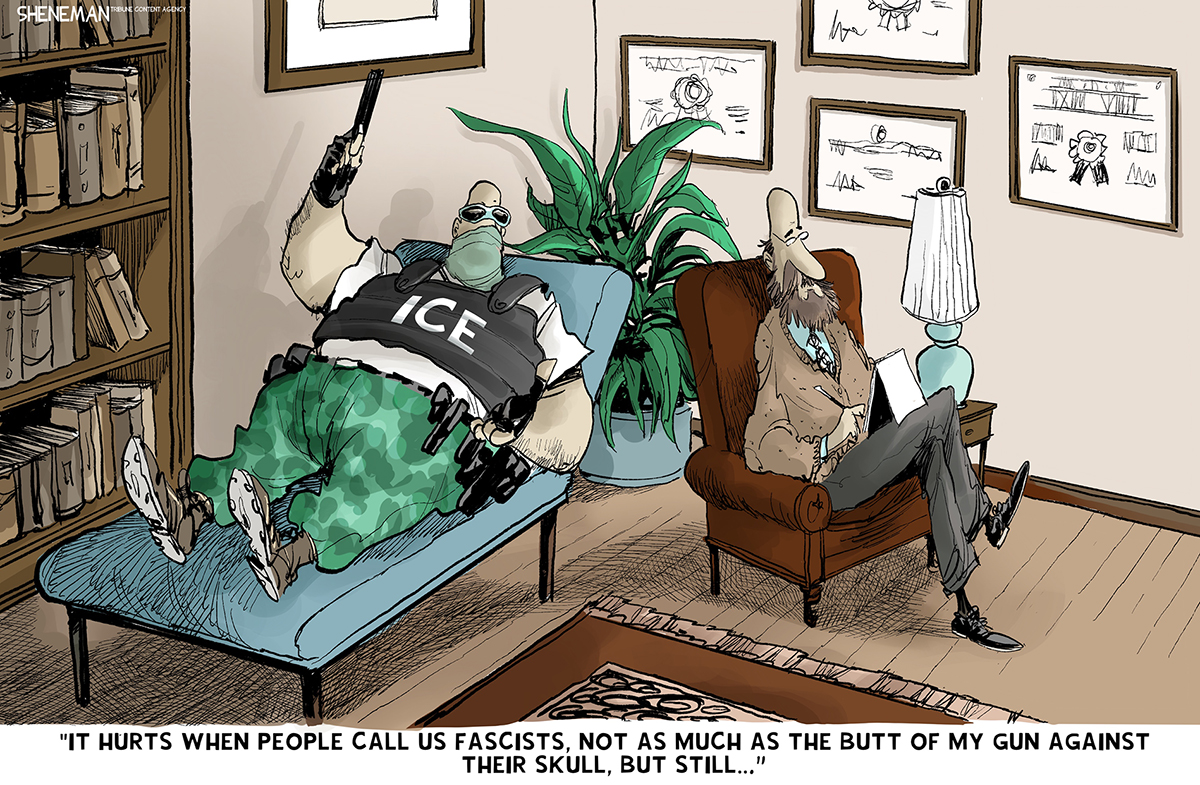

Political cartoons for February 5

Political cartoons for February 5Cartoons Thursday’s political cartoons include sticks and stones, the wake of nationalized elections, and more

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Supreme Court upholds California gerrymander

Supreme Court upholds California gerrymanderSpeed Read The emergency docket order had no dissents from the court

-

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?Talking Point Rambling speeches, wind turbine obsession, and an ‘unhinged’ letter to Norway’s prime minister have caused concern whether the rest of his term is ‘sustainable’

-

Why is Tulsi Gabbard trying to relitigate the 2020 election now?

Why is Tulsi Gabbard trying to relitigate the 2020 election now?Today's Big Question Trump has never conceded his loss that year

-

Will Democrats impeach Kristi Noem?

Will Democrats impeach Kristi Noem?Today’s Big Question Centrists, lefty activists also debate abolishing ICE

-

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?In the Spotlight Mass closure of shops and influx of organised crime are fuelling voter anger, and offer an opening for Reform UK

-

Do oil companies really want to invest in Venezuela?

Do oil companies really want to invest in Venezuela?Today’s Big Question Trump claims control over crude reserves, but challenges loom

-

What is China doing in Latin America?

What is China doing in Latin America?Today’s Big Question Beijing offers itself as an alternative to US dominance

-

Why is Trump killing off clean energy?

Why is Trump killing off clean energy?Today's Big Question The president halts offshore wind farm construction

-

Why does Trump want to reclassify marijuana?

Why does Trump want to reclassify marijuana?Today's Big Question Nearly two-thirds of Americans want legalization