The microchip war raging between the US and China

The US has been doing its best to hobble China’s electronic chipmaking industry. Why?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A new proxy war has been raging behind the scenes between China and the US with Washington doing its best to hobble Beijing’s electronic chipmaking industry.

In his second State of the Union address, Biden praised the CHIPS and Science Act passed last year, which “provides $52 billion in funding to subsidise semiconductor manufacturing in the US and billions in additional funding for emerging technology research and development”, said NextGov.

What’s happening?

Last October, the United States imposed a sweeping set of export control rules designed to restrict China’s ability both to obtain advanced computing chips and to manufacture them. Along with other measures, some dating back many years, this has created a “chip choke” in China, causing major damage to the country’s hi-tech sector by depriving it of access to critical technology.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Telecoms specialists such as Huawei and ZTE, and China’s leading chip manufacturers, SMIC and YMTC, have been particularly affected. Last week US diplomats stepped up their efforts, reportedly concluding a deal with Japan and the Netherlands that imposes new restrictions on exports of chipmaking tools to China. Many analysts have described these US policies together as a “declaration of economic war” on China.

Why are microchips so important?

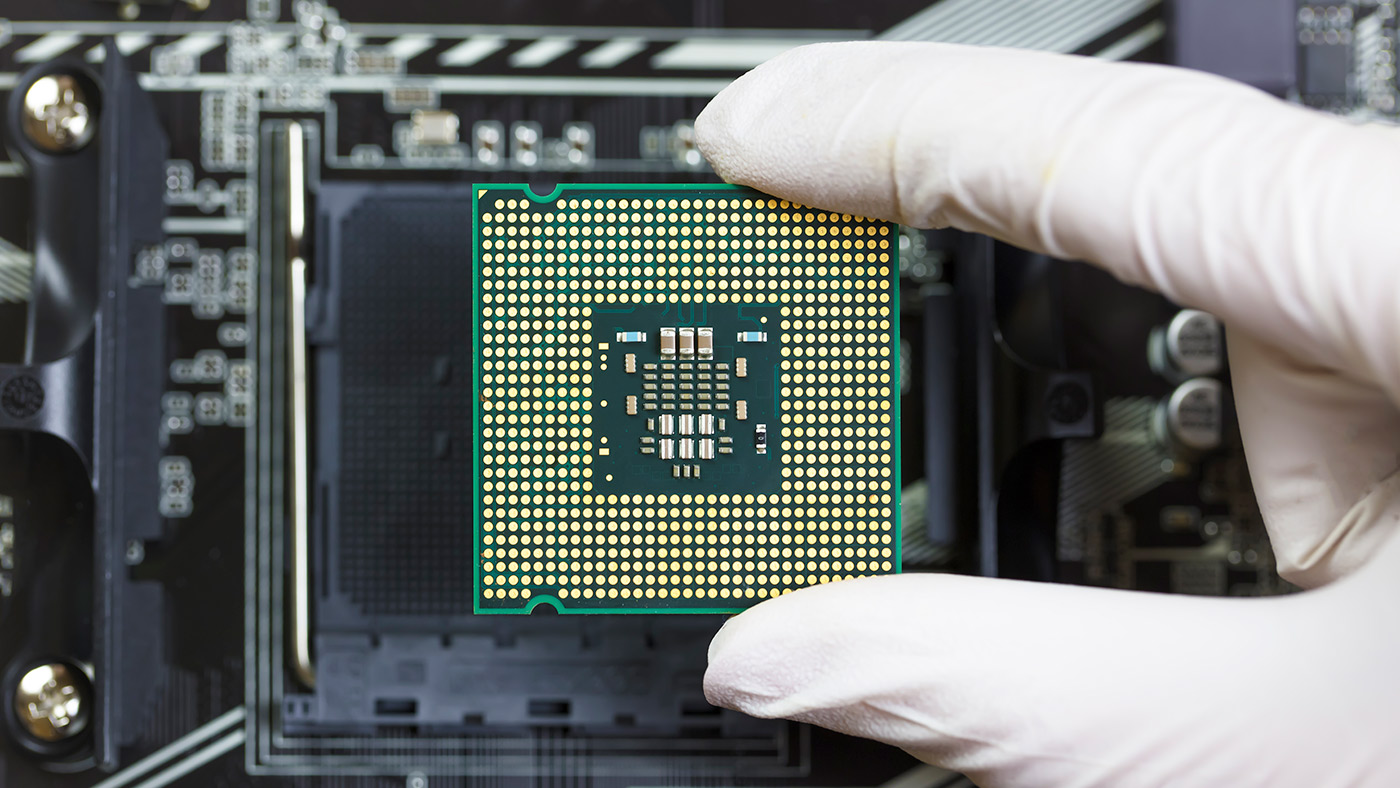

Microchips, or semiconductors, are needed to run just about any technology we use today, from the basic chips in fridges and toasters to the “leading edge” kind used in smartphones and data centres. That puts them at the centre of the world economy. Global sales of microchips were estimated at a whopping $573bn in 2022.

Chips are often described as “the new oil”; China now spends more money importing them than it does on oil. The pandemic revealed how dependent the global economy is on their supply, and also how complex and fragile the supply chain is; a shortage closed down car factories and caused electronics prices to spike.

There’s also a strong strategic, or national security, dimension to the issue. Advanced microchips are critical to military technology, and to intelligence gathering. Artificial intelligence, which is vital to both, and to many cutting-edge technologies, depends on large quantities of advanced chips.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Why are the supply chains so complex and fragile?

Chip fabrication plants (“fabs”) for advanced chips are among the world’s most complex manufacturing facilities; they can carve billions of tiny circuits into a silicon chip the size of a fingernail. Such fabs cost billions of dollars to build.

The manufacture of leading edge chips, used in computers and smartphones (and in AI), is dominated by a handful of companies such as the US firm Intel; Samsung of South Korea; and, most of all, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC). Around 90% of the most advanced chips are made in Taiwan.

The supply chains are global: a typical chip might be designed by engineers in California and Israel, using blueprints from a British-based company and US software, then manufactured in Taiwan, before being placed into a product in China. Yet parts of the chain are so specialised as to be, effectively, monopolies.

Which parts are monopolies?

There is only one company in the world that makes the machines that can print leading edge chips: ASML of the Netherlands. These machines use extreme ultraviolet lithography (EUV), a way of etching complex patterns onto silicon wafers only a few atoms thick.

ASML’s tools use the most powerful lasers ever deployed in a commercial device, heating tin to the temperature of the surface of the Sun to give off extreme ultraviolet light, which is then reflected using mirrors “so exact, they could be used to aim a laser to hit a golf ball as far away as the Moon”.

Both the expertise and the capital required mean that there are, at present, no effective competitors to ASML. And the US does not want these machines to fall into Chinese hands.

What is the overall aim of US policy?

The US has imposed export controls on microchips for many years, because of their military applications. But the latest restrictions mark a new determination to “decouple” its chip supply chains from China’s, and to end the shipping of high-end chips to its biggest strategic and commercial rival.

Last year, the US congress also passed the Chips and Science Act, which provided $52.7bn in new funding to boost domestic research and manufacturing of semiconductors in the US, so as to reduce reliance on Asia. Intel, Samsung, TSMC and Micron are all building new fabs in the US.

But perhaps more important, says Prof Chris Miller of Tufts University, the author of Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology, is the extensive research and development budget of $11bn, designed to ensure that US-based engineers continue to lead the world.

How has China responded?

China has launched a complaint at the World Trade Organisation, but a resolution could take years, and the US has invoked rules that allow nations to restrict trade to protect national security interests. Otherwise, China has yet to respond directly, which some see as an acceptance that its technological dependence gives it few options.

However, Beijing has itself had comparable policies in place since 2015, when it launched its Made in China 2025 plan, investing billions (and at times using outright property theft) in an attempt to achieve independence of foreign semiconductor suppliers by that date.

How will the conflict play out?

US pressure is having an effect: Apple has reportedly shelved plans to buy memory chips from China’s YMTC because of it; Huawei’s sales collapsed by 30% in 2021. For now, China makes only about 15% of the world’s chip supply, though it plays a big role in producing older, less advanced “lagging edge” chips.

For the next five years at least, the US and the other members of what it calls the “Chip 4 alliance” (Taiwan, South Korea and Japan) are likely to dominate the production of leading edge chips. In the long run, it seems likely that there will be rival microchip supply chain “ecosystems” inside and outside China. And the relative success of these is likely to have a powerful influence on the structure of the global economy and the balance of geopolitical power.