Dmitry Medvedev: Putin’s new ‘attack dog’

The former Russian president’s rhetoric is becoming increasingly aggressive

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Threats emanating from Russia have escalated in recent months, with the former prime minister and president Dmitry Medvedev leading the charge.

Medvedev, who according to The Independent was once seen as “the more liberal” counterbalance to Vladimir Putin, remains one of the president’s “closest aides and protégés” in his current capacity as deputy chair of Russia’s Security Council.

In recent months, Medvedev “has become Moscow’s primary mouthpiece for nuclear sabre-rattling”, added the news site, and recently issued “death threats” to Western nations and officials following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Most recently, Medvedev “ramped up the rhetoric”, said ITV News, by branding UK politicians “legitimate military targets” and accusing Westminster of “inciting Ukrainian ‘terrorists’”.

Who is Dmitry Medvedev?

Born on 14 September 1965, he was the son of teachers who lived in a suburb of what was then Leningrad, now St Petersburg.

His maths teacher, Irina Grigorovskaya, described him as “well read from a young age”, according to Reuters. “Although I lived behind the Soviet Iron Curtain,” Medvedev told ABC News in 2010, “the [Western] music seeped through.” He developed “a deep love of rock music”, including bands such as Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple and Pink Floyd.

Growing up, he “followed in his academic parents’ footsteps” to become a law professor. He graduated in 1987 from St Petersburg University, “which later become a source of the local and then Kremlin elite”, Reuters added.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

How did Medvedev meet Putin?

He was “one of the bright sparks from civil law”, said Nikolai Kropachev, current dean of the law faculty, who worked with Medvedev in the 1990s, according to Reuters. His association with Anatoly Sobchak, who was his professor of civil law, “propelled him… towards a life in government”, said The Guardian.

Medvedev “cut his political teeth while the Soviet Union was crumbling”, reported ABC News. When Sobchak became the chairman of Leningrad’s city council, he hired Medvedev as an adviser. Putin, another former student, became head of the committee for foreign relations, and “their political stars rose in tandem”.

Putin, “eight years older and with a Soviet world-view”, was “the dominant figure of the two”, The Guardian added. This was “a dynamic that would persist for 30 years”. He ran Putin’s presidential campaign in 2000 and was his chief of staff between 2003 and 2005, before becoming deputy prime minister between 2005 and 2008. He was “Putin’s handpicked successor” to become president in 2008, ABC News added, which led to allegations he is “little more than Putin’s puppet”.

How does Medvedev’s politics differ from Putin’s?

Medvedev was once viewed “as [Putin’s] more moderate successor”, said Frida Ghitis on CNN, and even tweeted in 2016 that it’s “Russia’s destiny to look both east and west”.

While serving as president between 2008 and 2012, Medvedev “become a symbol of what could be called a kinder, gentler Putinism”, wrote Mark Galeotti in The Spectator. He was, after all, “a technocrat in love with his Western iPhone and iPad”.

His rhetoric at the time “afforded hope” that he was “genuinely committed to a reform agenda”, said The Independent. When Medvedev became prime minister in 2012, many hoped “the more liberal of the two men” would “steer Russia in the direction of democratic reforms”.

What happened to Medvedev’s political career?

Medvedev became Putin’s prime minister for the next eight years but one diplomat observed in 2015 that “there is something broken in him now”, said The Spectator. “The job of the prime minister increasingly became that of majordomo at the tsar’s court”, and he was “more and more out of step with the new hawkishness that pervaded the court”.

There have been “embarrassing public moments” with the former president “spotted nodding off” during Putin’s presidential addresses, The Guardian said. Allegations of “personal corruption” weakened Medvedev “fatally”, which led Putin to replace him with Mikhail Mishustin in 2020.

Why has Medvedev ramped up the rhetoric?

Putin gave Medvedev “the new (and undefined)” role as deputy chair of the Security Council, which has “in practice left an increasingly depressed Medvedev in the position of class nerd forced to sit at the jocks’ table”, The Spectator said.

In recent years “Medvedev has emerged as the man who makes over-the-top threats for the regime”, CNN said. As well as threatening UK officials, he has contemplated a “nuclear apocalypse”, and characterised the Russian invasion “as a holy war waged against ‘crazy Nazi drug addicts’ in Ukraine”, said The Spectator.

His more aggressive public interventions could be a “former dove… trying to convince the hawks he’s one of them”, The Spectator continued, as well as being “a desperate attempt” by Medvedev “to continue to prove his loyalty and maybe even utility to the boss”.

Keumars Afifi-Sabet is a freelance writer at The Week Digital, and is the technology editor on Live Science, another Future Publishing brand. He was previously features editor with ITPro, where he commissioned and published in-depth articles around a variety of areas including AI, cloud computing and cybersecurity. As a writer, he specialises in technology and current affairs. In addition to The Week Digital, he contributes to Computeractive and TechRadar, among other publications.

-

Switzerland could vote to cap its population

Switzerland could vote to cap its populationUnder the Radar Swiss People’s Party proposes referendum on radical anti-immigration measure to limit residents to 10 million

-

Political cartoons for February 15

Political cartoons for February 15Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include political ventriloquism, Europe in the middle, and more

-

The broken water companies failing England and Wales

The broken water companies failing England and WalesExplainer With rising bills, deteriorating river health and a lack of investment, regulators face an uphill battle to stabilise the industry

-

New START: the final US-Russia nuclear treaty about to expire

New START: the final US-Russia nuclear treaty about to expireThe Explainer The last agreement between Washington and Moscow expires within weeks

-

What would a UK deployment to Ukraine look like?

What would a UK deployment to Ukraine look like?Today's Big Question Security agreement commits British and French forces in event of ceasefire

-

Trump peace deal: an offer Zelenskyy can’t refuse?

Trump peace deal: an offer Zelenskyy can’t refuse?Today’s Big Question ‘Unpalatable’ US plan may strengthen embattled Ukrainian president at home

-

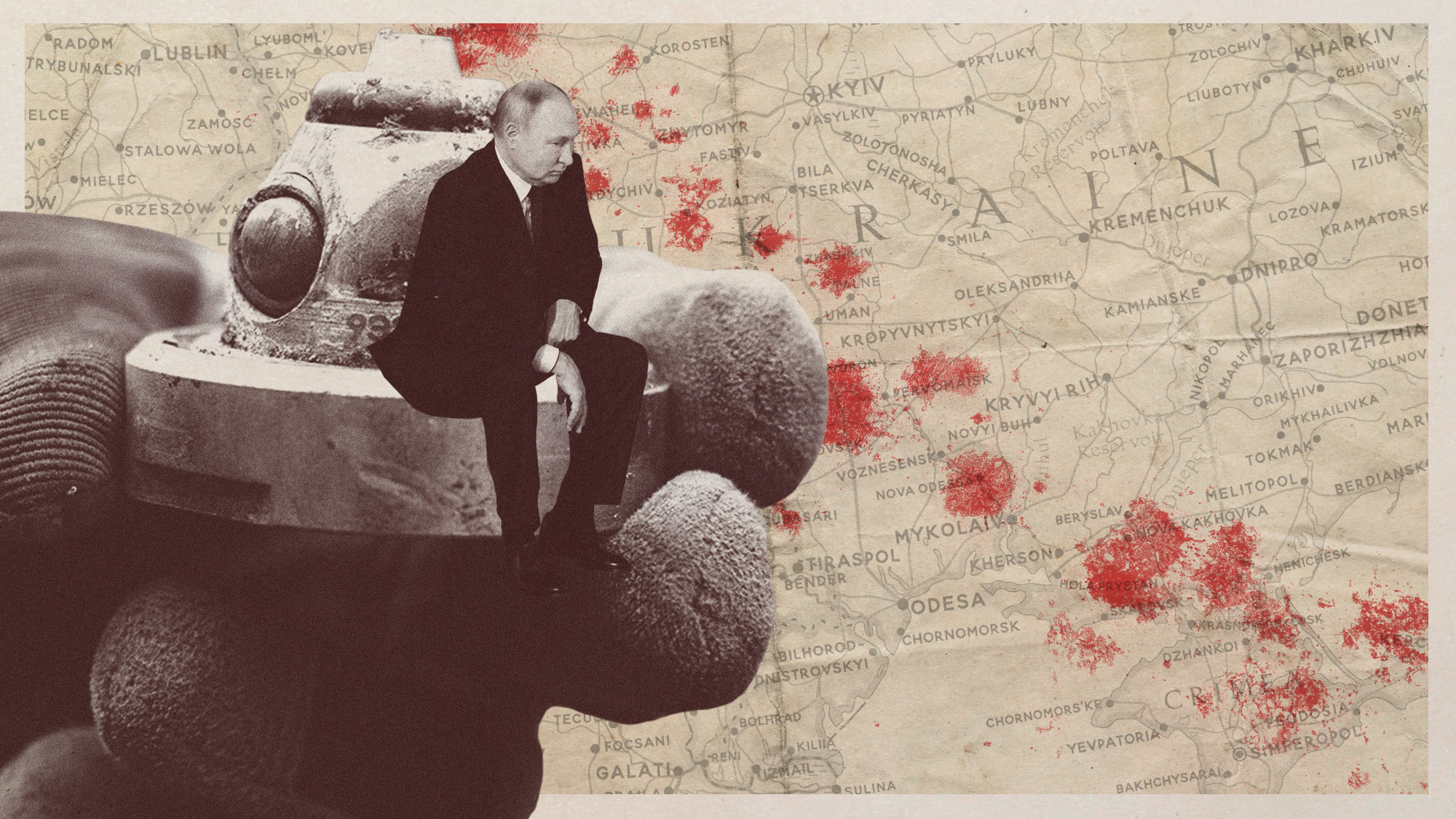

Vladimir Putin’s ‘nuclear tsunami’ missile

Vladimir Putin’s ‘nuclear tsunami’ missileThe Explainer Russian president has boasted that there is no way to intercept the new weapon

-

How should Nato respond to Putin’s incursions?

How should Nato respond to Putin’s incursions?Today’s big question Russia has breached Nato airspace regularly this month, and nations are primed to respond

-

Russia’s war games and the threat to Nato

Russia’s war games and the threat to NatoIn depth Incursion into Poland and Zapad 2025 exercises seen as a test for Europe

-

What will bring Vladimir Putin to the negotiating table?

What will bring Vladimir Putin to the negotiating table?Today’s Big Question With diplomatic efforts stalling, the US and EU turn again to sanctions as Russian drone strikes on Poland risk dramatically escalating conflict

-

Ottawa Treaty: why are Russia's neighbours leaving anti-landmine agreement?

Ottawa Treaty: why are Russia's neighbours leaving anti-landmine agreement?Today's Big Question Ukraine to follow Poland, Finland, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia as Nato looks to build a new ‘Iron Curtain' of millions of landmines