The future of drone warfare

Unmanned aerial weapons are reshaping the battlefield — and starting to think for themselves

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Unmanned aerial weapons are reshaping the battlefield — and starting to think for themselves. Here's everything you need to know:

When were drones first deployed?

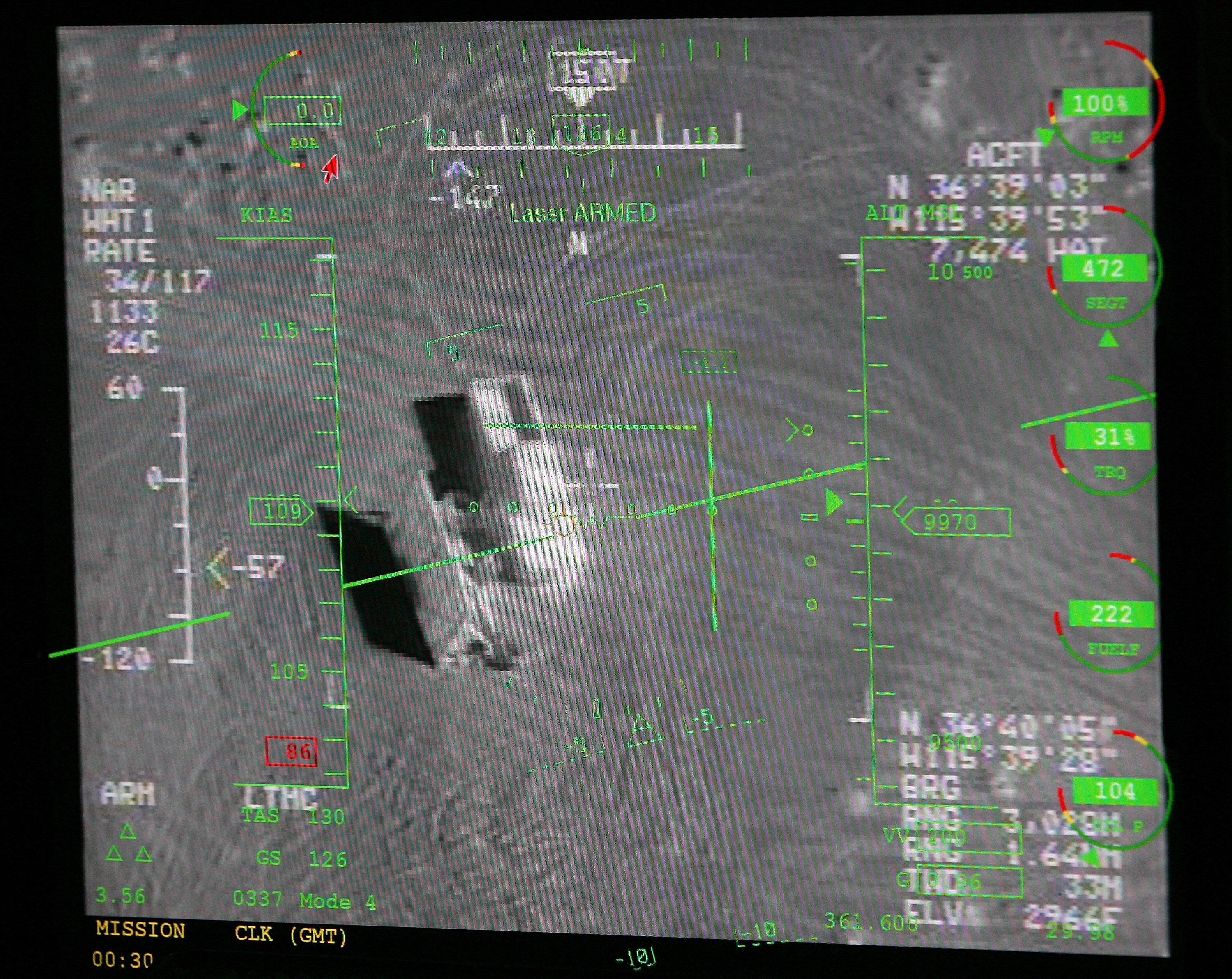

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) have been in use for decades. Radio-controlled B-24s were sent on bombing missions over Germany in World War II, and American forces used remote-controlled surveillance aircraft to snap photos during the Vietnam War. But the real breakthrough in drone warfare came in 1995 with the development of the Gnat — later renamed the Predator — an American UAV with a 49-foot wingspan that could stay airborne over a target for up to 12 hours, transmitting a live-video feed to a pilot who could be stationed hundreds or even thousands of miles away. On October 7, 2001, the first targeted strike by a remotely piloted aircraft took place in Afghanistan. A CIA Predator blasted a Hellfire-missile at a compound housing Taliban leader Mullah Omar; it missed and destroyed a nearby vehicle, killing several bodyguards. The U.S. drone program steadily expanded in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Pakistan, and by 2014 the Air Force was training more drone pilots than airplane pilots. Some 20 countries now have UAVs in their arsenals, up from eight in 2015.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What advantages do drones have over warplanes?

Unlike fighter jets, which need to be refueled regularly and have crews that get tired, drones can loiter in the air for up to 24 hours while carrying out surveillance, probing air defenses, or waiting for a suitable target. While drones such as the Predator are armed with missiles, a new generation of low-cost "kamikaze" drones are flown into their targets and then explode. Pentagon officials worry that the spread of these cheap and deadly-effective drones could help shift the global strategic balance away from the U.S. "Our adversaries are already fielding technologies that will hold our legacy platforms at risk," acting Air Force Secretary John Roth recently told Congress.

Where are these drones being made?

China is a top exporter. At least 10 countries — including Nigeria and the United Arab Emirates — have used Chinese-made UAVs to kill adversaries. Turkey has also emerged as a drone powerhouse. Its utilitarian Bayraktar TB2, a 21-foot-long UAV armed with four laser-guided missiles, first grabbed international attention in Syria in February 2020. After 36 Turkish troops were killed in a Syrian government airstrike, Turkey used a fleet of radio-guided TB2s — which are quiet and hard to spot on radar — to destroy Russian-made air defenses and kill hundreds, possibly thousands, of Syrian troops. TB2s also proved crucial in the Libyan civil war last year, helping the central government repel an assault on the capital, Tripoli, by the Russian-backed forces of rebel leader Khalifa Haftar. But the biggest demonstration of how drones are changing the nature of warfare was the 2020 conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh, an ethnic Armenian enclave inside Azerbaijan.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

How were drones used there?

At the start of the war, Azerbaijan sent slow-flying Soviet-era aircraft that had been converted to drones to bait Armenian air defense units — tempting them to fire and expose their location, at which point they could be hit by TB2s or Israeli-made kamikaze drones. Having achieved aerial dominance, Azerbaijani drones then devastated Armenian forces, destroying at least 106 Armenian tanks, 146 artillery pieces, and scores of other vehicles. After six weeks of fighting, the Armenians had no choice but to sign a humiliating truce. Nagorno-Karabakh, said Malcolm Davis of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, was "a potential game changer for land warfare."

How else are drones changing warfare?

Experts worry that the proliferation of UAVs could make bloody conflicts more common, because countries that are reluctant to start a war and risk their soldiers' lives won't hesitate to send in drones. "For states that seek to break long-standing geopolitical deadlocks, the rise of relatively cheap, disposable, armed drones offers a tempting opportunity," says Jason Lyall, an expert in military technology at Dartmouth College. Others fear a rise in autonomous drones that don't need a human controller. The United Nations recently reported that a 15-pound Turkish-built quadcopter independently targeted and launched a suicide attack on retreating rebel forces in Libya. If anyone died in that March 2020 strike, said security consultant Zachary Kallenborn, it would be the "first known case of artificial intelligence–based autonomous weapons being used to kill."

Are other nations making AI drones?

The U.S., China, Russia, and India are all experimenting with AI-driven drone swarms, in which dozens or hundreds of UAVs act in concert to overwhelm enemy forces. Some human rights organizations and AI researchers are calling for a ban on killer robots, saying that even if this technology does not result in the nightmare scenario from the Terminator movies — in which intelligent bots turn on their human inventors — drone proliferation is dangerous. "Lethal autonomous weapons cheap enough that every terrorist can afford them are not in America's national security interest," says MIT physicist Max Tegmark. But the major countries developing intelligent drones have shown no interest in a ban that they believe their rivals would not honor. "We're moving toward a situation with cyber or autonomous weapons," said German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas, "where everyone can do as they please."

Defending against drones

The drone arms race has sparked an anti-drone arms race. In 2019, the U.S. Army began using the Raytheon-developed Howler system, which can be attached to tanks and other vehicles and scans for enemy UAVs with radar. If it detects an incoming UAV, the Howler launches a 3-foot interceptor drone called the Coyote that detonates on impact, destroying itself and the threat. But using such a defense in a heavily populated area carries a high risk of civilian casualties, and so researchers are examining less explosive options. One interceptor drone created by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) blasts what appears to be silly string at the UAV, gumming up its rotors and causing it to fall from the sky. China, meanwhile, has developed a 20-barrel Gatling gun, which weapons experts believe is intended to counter the threat of drone swarms by throwing up a wall of bullets. But anti-drone research is still in its infancy, says Dartmouth's Lyall. "The defense is playing catch-up, while the offense marches downfield."

This article was first published in the latest issue of The Week magazine. If you want to read more like it, you can try six risk-free issues of the magazine here.