Are free votes the best way to change British society?

On 'conscience issues' like abortion and assisted dying, MPs are being left to make the most consequential social decisions without guidance

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In the space of a few days, two of the biggest social changes in a generation have been voted through by MPs in free votes, calling into question the legitimacy of the practice when it comes to so-called "matters of conscience".

On Tuesday, the House of Commons voted to decriminalise abortion in England and Wales, and today, MPs voted to legalise assisted dying. In both cases, MPs were told they can vote however they wanted, free from the usual pressure to follow the party line through the whips.

While "idealists might say these votes are the perfect example of what MPs used to be: free-thinking independent decision makers", said The Times, "the truth is a little murkier".

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What did the commentators say?

Votes of conscience are a "quasi-religious hangover" and "one of the most unthinkingly overrated elements of the British constitution", said Lewis Goodall on his Substack. "If a change is worth doing, it’s worth the government driving the change itself and arguing for it accordingly." It is not clear either why topics such as abortion and assisted dying are "any more or less inherently a matter of morality than any other sphere of political decision making".

Free votes on issues of conscience, while uncommon, "have defined our society", said Simon Griffiths on The Constitution Society. The late 1960s is "often seen as a golden age of social reform, and free votes were instrumental to this". Male homosexuality was legalised, capital punishment abolished, and laws relating to censorship, divorce and abortion all liberalised.

But on nearly all the main "conscience votes", party affiliation "remains the strongest indicator of how a representative will vote". In November, during the first vote on assisted dying, Labour MPs largely voted in favour while the Conservatives voted overwhelmingly against reform.

And in reality, both the changes voted on this week "would not have been possible without tacit support from the top of government", said The Times. "Parliament is geared to work around whatever the government wants, and mostly whenever the government wants it."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What next?

Keir Starmer has "done his best to stay out of these debates to avoid influencing his colleagues, and yet his support for both policies is still pretty well known", said the BBC. A free vote puts "some distance between the government and the legislation, meaning any political heat focuses on those debating the changes", said The Times.

In that way it "could be claimed the use of free votes demonstrates not a respect for issues of conscience, but rather a strategic decision by governments to free themselves of accountability", said Griffiths.

But Starmer will know that "however distant he seeks to be from the action in parliament", said The Times, these moments in social history "will form a central part of his legacy".

Jamie Timson is the UK news editor, curating The Week UK's daily morning newsletter and setting the agenda for the day's news output. He was first a member of the team from 2015 to 2019, progressing from intern to senior staff writer, and then rejoined in September 2022. As a founding panellist on “The Week Unwrapped” podcast, he has discussed politics, foreign affairs and conspiracy theories, sometimes separately, sometimes all at once. In between working at The Week, Jamie was a senior press officer at the Department for Transport, with a penchant for crisis communications, working on Brexit, the response to Covid-19 and HS2, among others.

-

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far right

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far rightIN THE SPOTLIGHT Reactions to the violent killing of an ultra-conservative activist offer a glimpse at the culture wars roiling France ahead of next year’s elections.

-

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?the explainer They are distinguished by the level of risk and the inclusion of collateral

-

‘States that set ambitious climate targets are already feeling the tension’

‘States that set ambitious climate targets are already feeling the tension’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Will Peter Mandelson and Andrew testify to US Congress?

Will Peter Mandelson and Andrew testify to US Congress?Today's Big Question Could political pressure overcome legal obstacles and force either man to give evidence over their relationship with Jeffrey Epstein?

-

How long can Keir Starmer last as Labour leader?

How long can Keir Starmer last as Labour leader?Today's Big Question Pathway to a coup ‘still unclear’ even as potential challengers begin manoeuvring into position

-

What is at stake for Starmer in China?

What is at stake for Starmer in China?Today’s Big Question The British PM will have to ‘play it tough’ to achieve ‘substantive’ outcomes, while China looks to draw Britain away from US influence

-

Can Starmer continue to walk the Trump tightrope?

Can Starmer continue to walk the Trump tightrope?Today's Big Question PM condemns US tariff threat but is less confrontational than some European allies

-

Alaa Abd el-Fattah: should Egyptian dissident be stripped of UK citizenship?

Alaa Abd el-Fattah: should Egyptian dissident be stripped of UK citizenship?Today's Big Question Resurfaced social media posts appear to show the democracy activist calling for the killing of Zionists and police

-

Is Keir Starmer being hoodwinked by China?

Is Keir Starmer being hoodwinked by China?Today's Big Question PM’s attempt to separate politics and security from trade and business is ‘naïve’

-

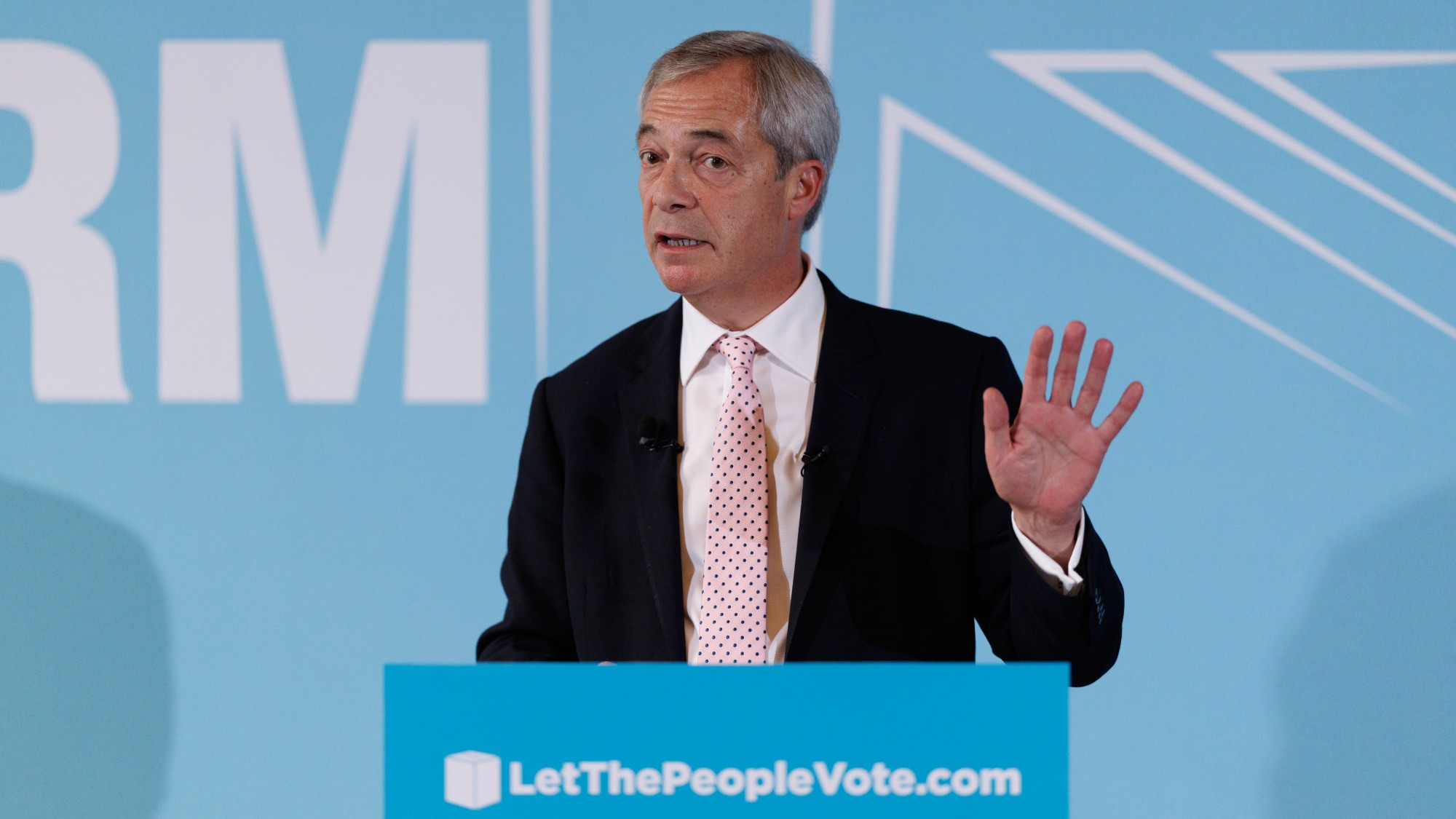

Nigel Farage’s £9mn windfall: will it smooth his path to power?

Nigel Farage’s £9mn windfall: will it smooth his path to power?In Depth The record donation has come amidst rumours of collaboration with the Conservatives and allegations of racism in Farage's school days

-

ECHR: is Europe about to break with convention?

ECHR: is Europe about to break with convention?Today's Big Question European leaders to look at updating the 75-year-old treaty to help tackle the continent’s migrant wave