How the UK's elections work

Everything you need to know about the mad dash to the finish in the UK

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

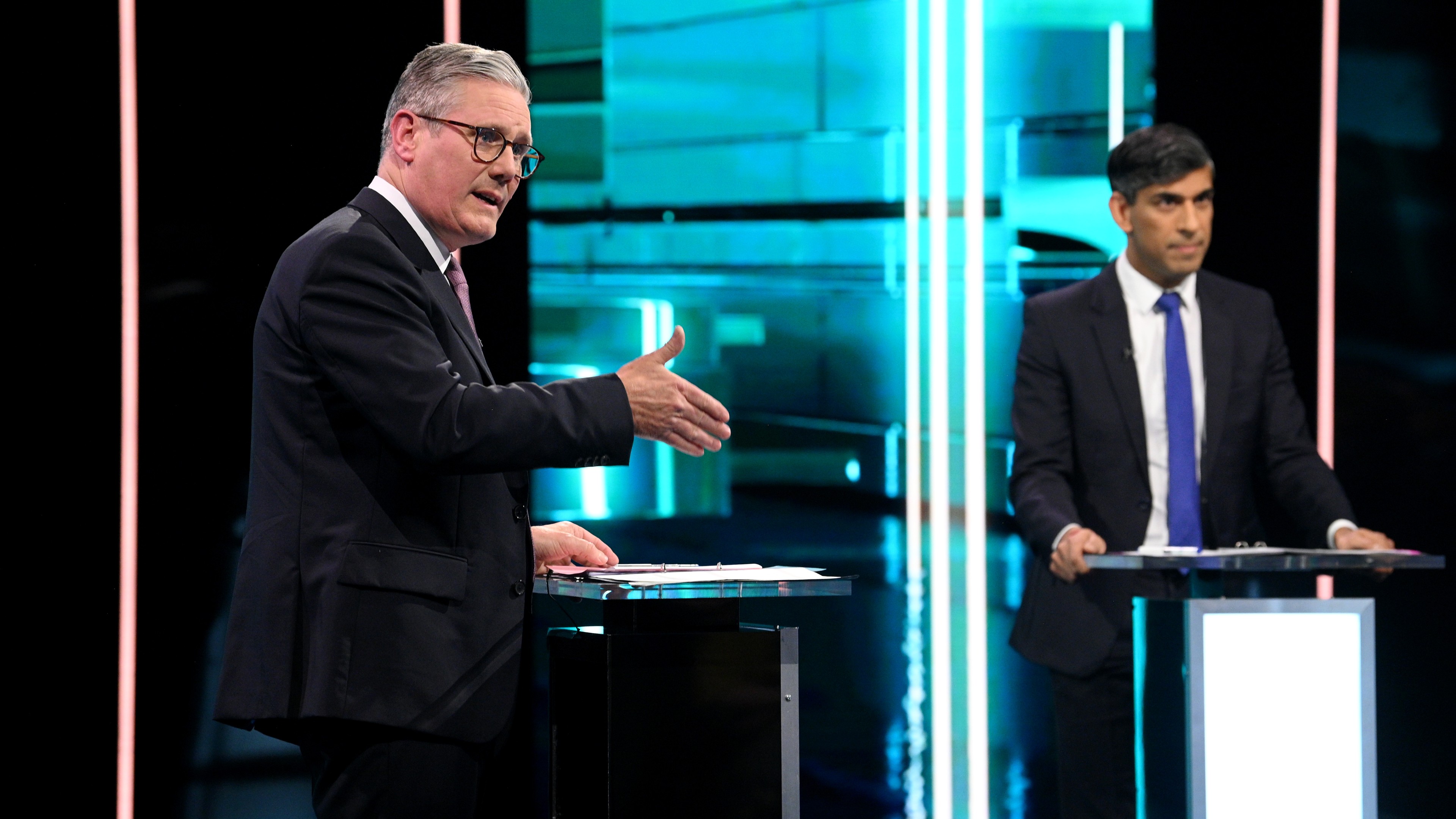

On July 4, the United Kingdom will hold its first general election since 2019. All 650 seats in the House of Commons are up for grabs, and Prime Minister Rishi Sunak's Conservatives, who have been in power for 14 years, look like long shots to retain their parliamentary majority. Public opinion polling has consistently shown the opposition Labour Party in the lead. Sunak's decision in May to call the snap election months earlier than required by law was likely made to capitalize on positive economic data, which Conservatives hope will turn around their flagging fortunes and prevent an expected Labour takeover. To do so, they need to keep Labour below 326 seats.

How does the UK's electoral system work?

The U.K. uses the same electoral system as the United States and Canada, known as Single Member District Plurality (SDMP). All 650 members of the House of Commons are elected individually by constituencies determined by regional boundaries, as with the U.S. district system. To win a constituency, candidates need only win the most votes, even if it is a plurality rather than a majority.

Unlike the United States, though, the U.K. has more than two parties capable of consistently winning seats in the national legislature. In Scotland, the Scottish National Party (SNP) — which supports Scottish secession from the U.K. and re-entry into the European Union — has won at least 35 seats in each of the past three general elections. The U.K. also features two left-of-center parties rather than one. The Labour Party has been the leading left-liberal party in the country for more than a century, but is joined in the fray by the Liberal Democrats, whose standing has yet to recover from the party's electorally disastrous coalition with the Conservatives in 2010-2015.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The multiparty nature of the system makes it possible that no one wins a majority in the House of Commons. This has happened twice this century and is referred to as a "hung Parliament." However, current opinion polling suggests that the opposition will win a healthy majority in Parliament, with forecasts predicting anywhere from 394 to 475 seats for leader Keir Starmer's Labour Party. Though Labour is polling at 43.9% in the Financial Times average as of June 10, the nature of the British electoral system will likely deliver them a substantial majority if those numbers hold. In 2019, for example, the Conservatives won 43.6% of the popular vote but more than 56% of the seats in the House of Commons.

How does the snap election affect things?

In contrast to American presidential elections, which last 18 months or longer, the U.K.'s elections happen very quickly. When a snap election is called, it starts a clock of 25 working days from the King's official dissolution of Parliament to the election. The decision to hold an election also dissolves Parliament after a short period known as the "wash-up," when members can take care of any last-minute business. In the U.S. this happens after the general election and is known as the "lame-duck session." Therefore, during the weeks after an election is called until the day that a new Prime Minister is invited to form a government by the King, the U.K. lacks a Parliament. The Prime Minister and cabinet continue to govern as caretakers.

The most pressing issue in the election is the economy, which remains sluggish compared to other advanced democracies. GDP per capita has yet to return to what it was before the Great Recession, and many observers argue that Brexit is at least partially to blame. "No one doubts now," said Bloomberg's Michael A. Winkler, "that Brexit hindered rather than helped the ailing British economy." And since the Covid-19 pandemic, the U.K. has experienced higher inflation and slower growth than most countries in the Eurozone. That, combined with high interest rates on loans, has put the electorate in a sour mood, as is currently the case in nearly all rich democracies. Whether they will ultimately toss the Conservatives out, though, is up to the voters on July 4.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

David Faris is a professor of political science at Roosevelt University and the author of "It's Time to Fight Dirty: How Democrats Can Build a Lasting Majority in American Politics." He's a frequent contributor to Newsweek and Slate, and his work has appeared in The Washington Post, The New Republic and The Nation, among others.

-

Political cartoons for February 9

Political cartoons for February 9Cartoons Monday's political cartoons include 100% of the 1%, vanishing jobs, and Trump in the Twilight Zone

-

Who is Starmer without McSweeney?

Who is Starmer without McSweeney?Today’s Big Question Now he has lost his ‘punch bag’ for Labour’s recent failings, the prime minister is in ‘full-blown survival mode’

-

Hotel Sacher Wien: Vienna’s grandest hotel is fit for royalty

Hotel Sacher Wien: Vienna’s grandest hotel is fit for royaltyThe Week Recommends The five-star birthplace of the famous Sachertorte chocolate cake is celebrating its 150th anniversary

-

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’Talking Point Reform and the Greens have the Labour seat in their sights, but the constituency’s complex demographics make messaging tricky

-

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire tax

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire taxTalking Points Californians worth more than $1.1 billion would pay a one-time 5% tax

-

Trump links funding to name on Penn Station

Trump links funding to name on Penn StationSpeed Read Trump “can restart the funding with a snap of his fingers,” a Schumer insider said

-

Trump reclassifies 50,000 federal jobs to ease firings

Trump reclassifies 50,000 federal jobs to ease firingsSpeed Read The rule strips longstanding job protections from federal workers

-

Supreme Court upholds California gerrymander

Supreme Court upholds California gerrymanderSpeed Read The emergency docket order had no dissents from the court

-

Trump demands $1B from Harvard, deepening feud

Trump demands $1B from Harvard, deepening feudSpeed Read Trump has continually gone after the university during his second term

-

House ends brief shutdown, tees up ICE showdown

House ends brief shutdown, tees up ICE showdownSpeed Read Numerous Democrats joined most Republicans in voting yes

-

The Mandelson files: Labour Svengali’s parting gift to Starmer

The Mandelson files: Labour Svengali’s parting gift to StarmerThe Explainer Texts and emails about Mandelson’s appointment as US ambassador could fuel biggest political scandal ‘for a generation’