Keir Starmer: The Biography – five things we learned

New book offers glimpses behind the Labour leader's political persona

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Opinion polls suggest Keir Starmer is almost certain to be Britain's next prime minister, but many voters are far less clear about what lies behind the Labour leader's mask.

Some answers may be found in a new biography by Tom Baldwin, a "political correspondent steeped in New Labour legend", said Robert McCrum in The Independent. Although "unauthorised", said Ben Riley-Smith in The Telegraph, "Keir Starmer: The Biography" leans on "unparalleled access to Sir Keir and his inner circle", enabling Baldwin to "flesh out a public figure" who has been "reluctant to open up about his private life".

Here are five things revealed by the new book, out next week.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

'Complex' family relationships

Starmer is "quoted frequently and candidly" about his childhood in the new biography, said Riley-Smith, and his "adoration" for his mother, Jo, "shines through". She had Still's disease, which eventually led to her requiring a wheelchair. The resulting "assumption of responsibility at home throughout his school years" may be why Starmer has such a "sober, sincere, public service-minded approach today".

His relationship with father, Rodney, was more "complex", Riley-Smith wrote. The Labour leader visited his father in hospital shortly before his death, in 2018, but "regrets to this day" that he "didn't tell his father how much he meant to him". Rodney was "intimidating to some, stand-offish to others", but was said by those who knew him to "have a good heart".

And despite his "surliness", said Robbie Griffiths in the London Evening Standard, a "stash of newspaper clippings" found after his death "showed that Rodney had been quietly proud of his son".

The new biography also reveals what the Labour leader told Baldwin was his "real, deep sadness" for his younger brother, Nick. Starmer said his brother has had a "really tough life" after complications at birth resulted in learning difficulties.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Starmer's 'footballism'

There is an "absence of Labour theory" in the book, said McCrum in The Independent, and "virtually no reference to political philosophy". But Baldwin does analyse Starmer's "footballism", and how the game has "shaped his understanding of the English voters' sense of place" and "identity".

An Arsenal fan who regularly attends games at the Emirates Stadium in London, Starmer also frequently plays football on Sundays with "old friends who have nothing to do with Westminster" near his home in Kentish Town, north London. These games help to "keep his feet on the ground".

Politicians who "play the football card" may make "cynical commentators recoil in horror", said McCrum. But the biographer seems convinced that football is the driving force behind Starmer's "pragmatic reluctance to be pigeonholed ideologically" and his "dedication to the art of winning".

'No smoking gun'

The book paints a portrait of a man with a "fiercely competitive desire to win" who is "willing to do whatever it takes", said Gaby Hinsliff in The Guardian. But Baldwin declares at the outset that anyone "hoping to find these pages spattered with blood".

The biography reveals no "uncharacteristically juicy" scandals "lurking" in Starmer's history, Hinsliff said. And there is "no smoking gun" from his time as director of public prosecutions either.

The biographer describes Starmer's time at the Crown Prosecution Service as "one of diligently prosecuting sexual abuse cases previously treated as too difficult".

Brexit, Corbyn and leadership

Diving into politics at the age of 52, Starmer assumed he might have "quickly" become a minister had Labour won the 2015 election, wrote Andrew Marr in The New Statesman. Instead, the next five years in opposition felt "like a prison sentence", Starmer recalled.

This "sense of powerlessness was reinforced" by Jeremy Corbyn becoming Labour leader and by Brexit, said Marr. Starmer "did not admire Corbyn personally" and only stayed in his role to "wage a parliamentary fight for a softer Brexit".

The book "convincingly argues" that Starmer was "no enthusiast for reversing Brexit". Yet he sparked "furious reactions" from Corbyn's team when he put Remain as an option in a second referendum without authorisation, said Marr. It was seen by Tories as a "cynical trick" to "prepare for a leadership contest". Starmer said it was his attempt to "fix the problem".

His "careful" and "quietly planned" push to become leader was in the works even before Labour's 2019 general election defeat, said Marr. By then, Starmer was prepared to "woo members by talking left" and then "ditch the commitments he made" once he'd taken control of the party.

Close to resigning

Starmer allegedly had to be "persuaded to stay" after Labour lost the Hartlepool constituency in 2021, a seat it had held since 1974. The new book suggests that Starmer told "close aides in the immediate aftermath" that he would step down, said Nadeem Badshah in The Guardian.

Chris Ward, a former aide, told Baldwin that Starmer initially intended to stand down because he saw the result as "a personal rejection", and a sign that "the party was going backwards". Starmer's wife, Victoria, was "among those who urged him not to act too hastily" in the wake of the defeat.

To Starmer, the defeat felt like he had been "kicked in the guts", he is quoted as saying in the biography. It was a moment when he thought "we are not going to be able to do this".

Richard Windsor is a freelance writer for The Week Digital. He began his journalism career writing about politics and sport while studying at the University of Southampton. He then worked across various football publications before specialising in cycling for almost nine years, covering major races including the Tour de France and interviewing some of the sport’s top riders. He led Cycling Weekly’s digital platforms as editor for seven of those years, helping to transform the publication into the UK’s largest cycling website. He now works as a freelance writer, editor and consultant.

-

Political cartoons for February 15

Political cartoons for February 15Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include political ventriloquism, Europe in the middle, and more

-

The broken water companies failing England and Wales

The broken water companies failing England and WalesExplainer With rising bills, deteriorating river health and a lack of investment, regulators face an uphill battle to stabilise the industry

-

A thrilling foodie city in northern Japan

A thrilling foodie city in northern JapanThe Week Recommends The food scene here is ‘unspoilt’ and ‘fun’

-

The Mandelson files: Labour Svengali’s parting gift to Starmer

The Mandelson files: Labour Svengali’s parting gift to StarmerThe Explainer Texts and emails about Mandelson’s appointment as US ambassador could fuel biggest political scandal ‘for a generation’

-

Will Peter Mandelson and Andrew testify to US Congress?

Will Peter Mandelson and Andrew testify to US Congress?Today's Big Question Could political pressure overcome legal obstacles and force either man to give evidence over their relationship with Jeffrey Epstein?

-

Reforming the House of Lords

Reforming the House of LordsThe Explainer Keir Starmer’s government regards reform of the House of Lords as ‘long overdue and essential’

-

A running list of everything Donald Trump’s administration, including the president, has said about his health

A running list of everything Donald Trump’s administration, including the president, has said about his healthIn Depth Some in the White House have claimed Trump has near-superhuman abilities

-

How long can Keir Starmer last as Labour leader?

How long can Keir Starmer last as Labour leader?Today's Big Question Pathway to a coup ‘still unclear’ even as potential challengers begin manoeuvring into position

-

What is at stake for Starmer in China?

What is at stake for Starmer in China?Today’s Big Question The British PM will have to ‘play it tough’ to achieve ‘substantive’ outcomes, while China looks to draw Britain away from US influence

-

Can Starmer continue to walk the Trump tightrope?

Can Starmer continue to walk the Trump tightrope?Today's Big Question PM condemns US tariff threat but is less confrontational than some European allies

-

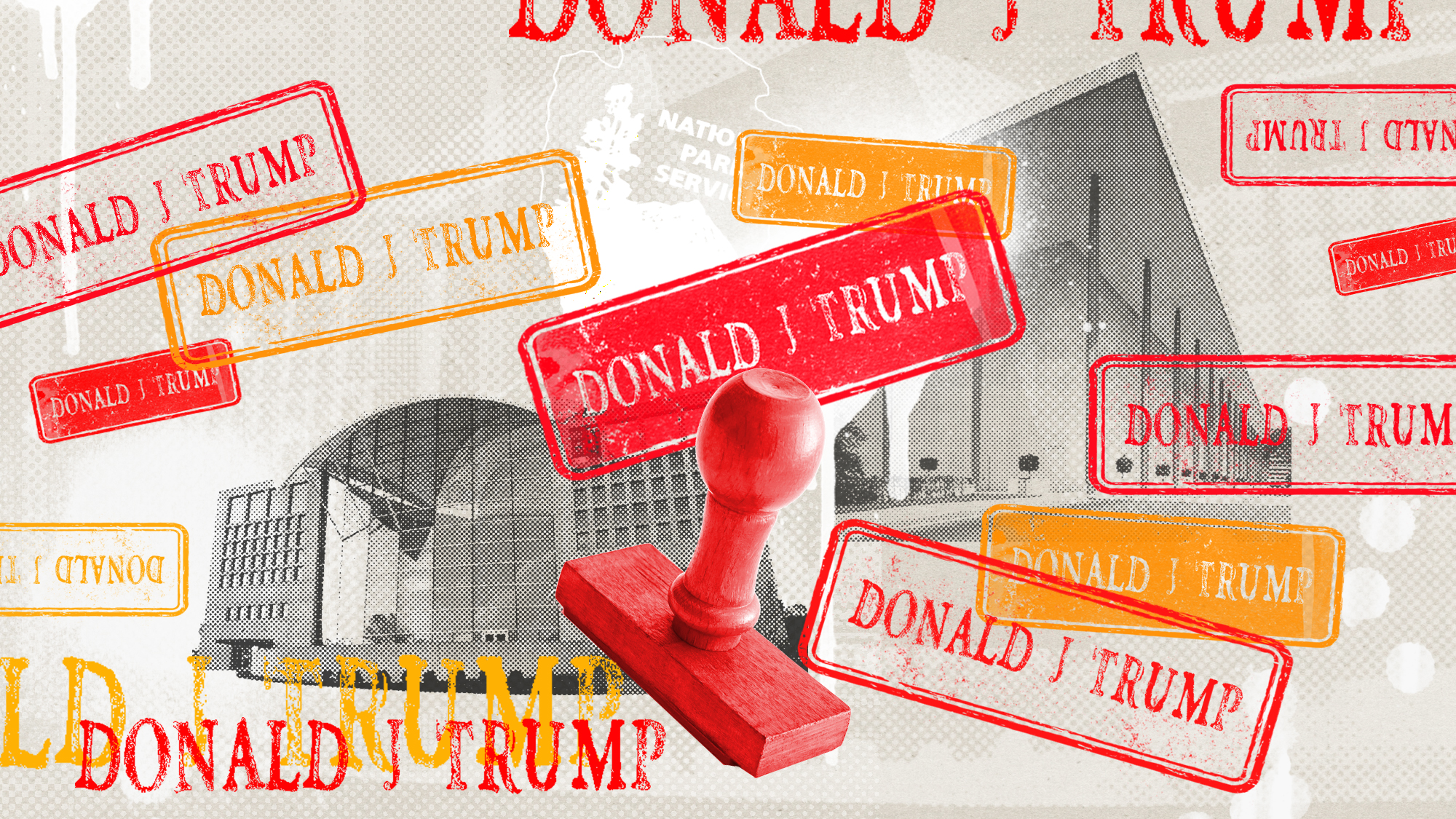

A running list of everything Trump has named or renamed after himself

A running list of everything Trump has named or renamed after himselfIn Depth The Kennedy Center is the latest thing to be slapped with Trump’s name