What can Labour learn from the left in Denmark about immigration?

The Nordic government's surprisingly strict approach has been hailed a success by some

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Denmark's centre-left government has a "zero refugee" policy, confiscates wedding rings and other valuables from refugees to cover costs, and blocks benefits for migrants who don't learn the national language.

When controlling immigration, "few countries in Europe are quite as tough and quick to act as Denmark", said Peter Conradi in The Times.

But policies of the centre-left government, led by Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen, have "succeeded in keeping immigration numbers down, her party's poll numbers up and the far right away from power", even as far-right parties surge elsewhere in Europe.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"Could the country that gave us Lego, hygge and the weight-loss drug Ozempic be a role model for Sir Keir Starmer as he struggles to ward off the threat from Nigel Farage and Reform?"

What did the commentators say?

Back in the UK, Keir Starmer’s claim that the country risks becoming an "island of strangers" without stricter immigration controls sparked "outrage on the left" and comparisons to Enoch Powell. Yet, "rather than empowering the far-right, Starmer may be neutering it", said Eir Nolsøe in The Telegraph.

As Danish immigration minister Kaare Dybvad Bek told the paper: "There is no doubt in my mind that traditional political parties taking immigration seriously is the reason why we don't have large far-right parties in Denmark." And despite criticism, Denmark's tough policies have voter backing; the Social Democrats won elections in 2019 and 2022.

In 2023, Denmark revoked residency permits for Syrian refugees, declaring parts of Syria safe, "before backtracking after international backlash", said Politico. Two years earlier, it passed a law allowing refugees to be relocated to asylum centres in countries like Rwanda, drawing criticism from the European Commission. The country has also "looked hard" at detaining asylum seekers on a remote island.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Rejected asylum seekers in Denmark receive no financial support, only food and shelter until they leave. Those who withdraw their application within two weeks get 20,000 DKK (£2,258), plus another 20,000 DKK in "repatriation support" to restart their lives. "Denmark literally pays migrants to leave," said Nolsøe.

Frederiksen justifies her "tough" migration rules through issues more traditionally associated with the left: "public services", said Katya Adler for the BBC. Danes pay the highest tax rates in Europe across all household types, and they "expect top-notch public services in return". The Danish prime minister argues that migration levels "threatened social cohesion and social welfare with the poorest Danes losing out the most". Her critics see this stance as a "cynical ploy", while she argues its sincerity but either way, it's worked: asylum claim applications are down in Denmark, in "stark contrast" to much of the rest of Europe.

At the heart of Frederiksen's approach is a "determination" to protect working-class livelihoods and prevent schools and welfare systems from being overwhelmed, said Sue Reid in the Daily Mail.

Government data supports this. In Danish schools, the younger the pupils, the higher the proportion of ethnic Danes, which is "the reverse of what is happening in much of England's education system", where last year 37% of pupils came from minority backgrounds.

This contrast offers a "stark lesson" for Labour. And with immigration dominating May's local elections, Denmark’s "hardline stance" is now "firmly" on Starmer’s radar following his meeting with Frederiksen in February.

What next?

Whether or not Denmark's immigration policies have been a success depends on the criteria used "to judge them", said Adler. Asylum claim applications are certainly down, but Denmark is not a "front-line state", where people smugglers' boats frequently aim for its shores.

And Denmark's hard-line stance and new legislation have seriously damaged its reputation for "respecting international humanitarian law and the rights of asylum-seekers", added Adler.

For this reason, among others, it would be "hard" for Starmer to "pursue" the Denmark approach, said Susi Dennison, senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations. Especially so because, after taking over from the Tories, Starmer "made a point" of recommitting the UK to international institutions and international law.

Chas Newkey-Burden has been part of The Week Digital team for more than a decade and a journalist for 25 years, starting out on the irreverent football weekly 90 Minutes, before moving to lifestyle magazines Loaded and Attitude. He was a columnist for The Big Issue and landed a world exclusive with David Beckham that became the weekly magazine’s bestselling issue. He now writes regularly for The Guardian, The Telegraph, The Independent, Metro, FourFourTwo and the i new site. He is also the author of a number of non-fiction books.

-

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?Podcast Plus, what does the growing popularity of prediction markets mean for the future? And why are UK film and TV workers struggling?

-

Properties of the week: pretty thatched cottages

Properties of the week: pretty thatched cottagesThe Week Recommends Featuring homes in West Sussex, Dorset and Suffolk

-

The week’s best photos

The week’s best photosIn Pictures An explosive meal, a carnival of joy, and more

-

ICE eyes new targets post-Minnesota retreat

ICE eyes new targets post-Minnesota retreatIn the Spotlight Several cities are reportedly on ICE’s list for immigration crackdowns

-

How did ‘wine moms’ become the face of anti-ICE protests?

How did ‘wine moms’ become the face of anti-ICE protests?Today’s Big Question Women lead the resistance to Trump’s deportations

-

The UK expands its Hong Kong visa scheme

The UK expands its Hong Kong visa schemeThe Explainer Around 26,000 additional arrivals expected in the UK as government widens eligibility in response to crackdown on rights in former colony

-

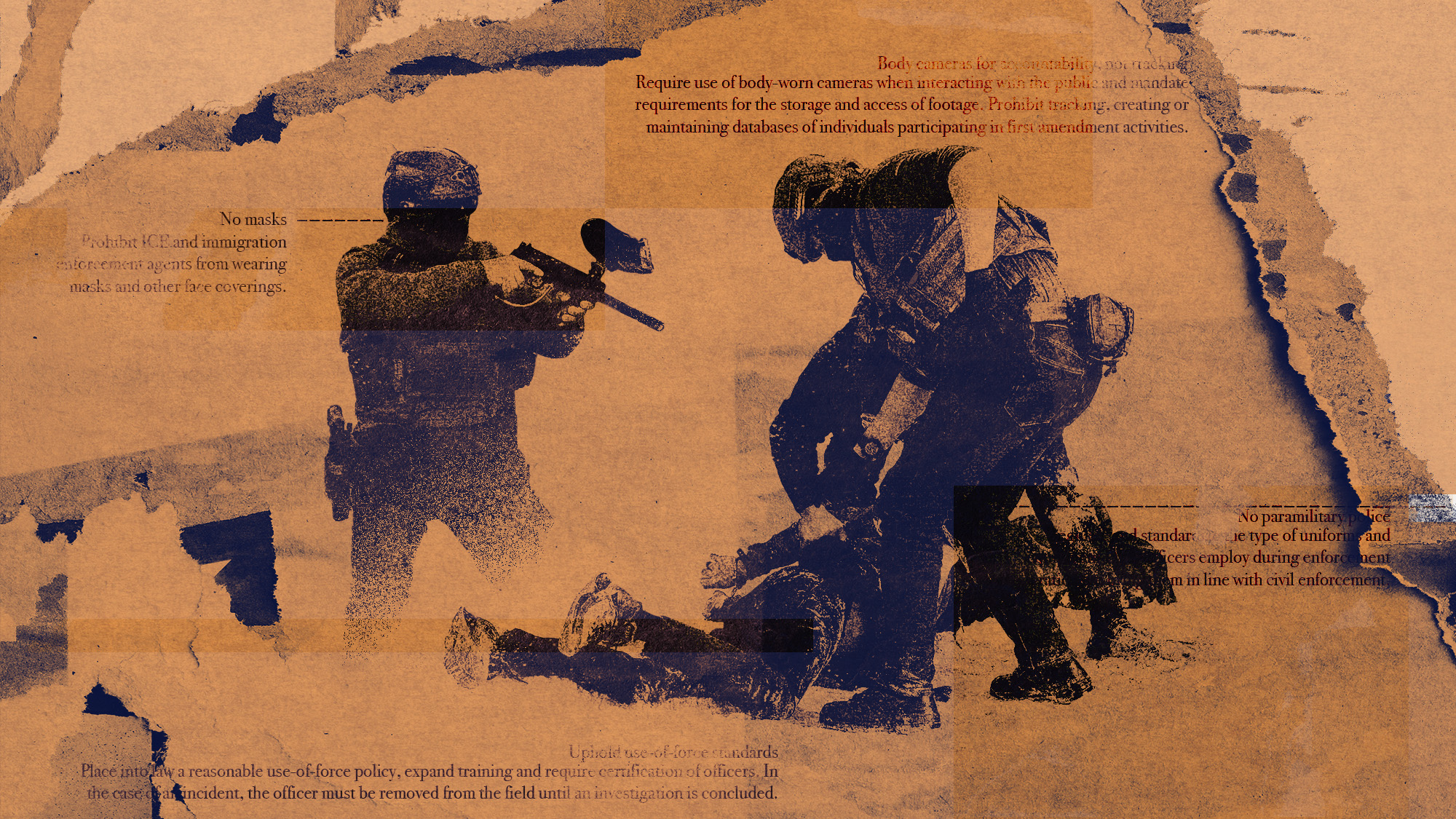

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?Today’s Big Question Democratic leadership has put forth several demands for the agency

-

Minnesota’s legal system buckles under Trump’s ICE surge

Minnesota’s legal system buckles under Trump’s ICE surgeIN THE SPOTLIGHT Mass arrests and chaotic administration have pushed Twin Cities courts to the brink as lawyers and judges alike struggle to keep pace with ICE’s activity

-

‘The West needs people’

‘The West needs people’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

700 ICE agents exit Twin Cities amid legal chaos

700 ICE agents exit Twin Cities amid legal chaosSpeed Read More than 2,000 agents remain in the region

-

House ends brief shutdown, tees up ICE showdown

House ends brief shutdown, tees up ICE showdownSpeed Read Numerous Democrats joined most Republicans in voting yes