Who is voting for the far-right in Europe?

Migration fears have fuelled a rising tide of right-wing populism, but migration alone is not the full story

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A new generation of right-wing politicians is making steady progress across much of Europe, where, in June, far-right parties gained a record 24% of all seats in the European Parliament. In France, that result prompted Emmanuel Macron to call a snap parliamentary election: Marine Le Pen's National Rally (RN) won the first round, gaining 33% of the vote (though it faltered in the second round). But the surge in support for RN reflects a wider trend across the continent?

Where else is the far–right on the rise?

In the Netherlands, a new far-right coalition took office in July, following Geert Wilders's shock election win last year. In Italy, Giorgia Meloni's Brothers of Italy, a party with neo-fascist roots, has been in power since 2022. In Hungary, Viktor Orbán has led an illiberal nationalist government since 2010.

The nationalist Sweden Democrats are the second-largest force in the country's parliament; the far-right Freedom Party (FPÖ) has led Austrian opinion polls for more than a year; and the nationalist Chega (Enough) finished third in elections in Portugal in March. Most recently, Alternative for Germany (AfD) won state elections in Thuringia, and was slated to win again in another eastern state, Brandenburg, this weekend.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Why are these parties classed as far-right?

The terminology is contested, but the far-right is usually divided into the "extreme right", which is overtly anti-democratic and racist (such as the neo-Nazi Golden Dawn in Greece) and the "radical populist" or "hard-right", such as the parties above. They don't speak with a single voice, but share a strong opposition to immigration, and a hostility to different cultures and religions – particularly to Islam.

Most are socially ultra-conservative, critical of LGBTQ+ rights, and concerned about Europe's low birth rates. They tend to be strongly nationalistic, eurosceptic, and to use populist rhetoric that puts them on the side of "the people" against a corrupt elite. Most are sceptical about climate change and policies designed to combat it; pro-Russian sympathies and opposition to aid for Ukraine are also widespread. Such parties are avowedly democratic but may seek to erode democratic norms, such as the rule of law and minority rights: Orbán's Fidesz party has curtailed media freedom and amended Hungary's constitution to entrench his power.

How do they differ?

In general, the closer they get to power, the less extreme they become. Leaders such as Meloni and Le Pen have, to some extent, detoxified their brands by stamping out overt racism among members. Arguably, in power Meloni has governed as a traditional conservative: she is fiscally moderate, has abandoned the idea of leaving the euro, and is staunchly supportive of Ukraine.

By contrast, Orbán's Fidesz is notably pro-Russian, as is Austria's FPÖ; while Wilders's Party for Freedom and the AfD also support ending military aid to Ukraine. Politically, the AfD is more extreme than its French and Italian counterparts, but it promotes neoliberal economics – while Le Pen's RN favours very high public spending and a generous welfare state (it would reduce the pension age to 60).

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What explains their appeal?

It is based to a large extent on voters' increasing concerns about migration. The parties' successes in recent years have been incremental, but support for many leapt up following the European migration crisis of 2015. Far-right parties tend to put immigration symbolically central in a wider story about national decline, economic difficulties and shortages of housing and welfare services.

And there have, of course, been many economic upheavals over this period – the long European sovereign debt crisis in the 2010s, along with the painful austerity measures and low investment that followed. Because of the pandemic and the Ukraine War, sharp inflation has meant that, across the EU, wages have declined in real terms since Covid. Far-right parties offer a radical alternative to a difficult status quo.

Are other factors involved?

The traditional conservative parties and their social democratic equivalents have arguably huddled on the centre ground in recent years – on austerity, for instance. This has opened up a market for radical alternatives: according to research by the University of Amsterdam, 32% of EU voters opted for anti-establishment parties in 2022, up from 12% in the early 1990s. Meanwhile, the radical Left has become deeply concerned with racism, transgenderism and other non-economic issues, while the radical Right offers simplistic answers to pressing everyday problems.

Who votes for them?

The traditional image of a far-right voter is of a disenfranchised white man, usually older than average. In Europe today, that has changed. Taboos dating back to the Second World War, which once prevented voters supporting far-right parties, are gradually being eroded. Far-right parties are being normalised. In some cases this has also led mainstream parties to abandon the "cordon sanitaire" – formal or informal pacts that once precluded them from cooperating with far-right parties. Norway, Sweden, Finland and, most recently, the Netherlands have all formed coalitions that included the far-right.

What does the future hold?

The continued rise of far-right parties isn't a foregone conclusion: Poland's right-wing populist Law and Justice party was defeated by Donald Tusk's centrist opposition last year, and they underperformed in June's EU elections in countries such as Finland, Sweden and Belgium.

But all the indications are that such parties are here to stay, and edging closer to power. They have already forced mainstream parties to shift their positions, primarily by taking harder lines on migration and asylum. Their influence is likely to be felt strongly on issues such as fossil fuel use and support for Ukraine. They remain fragmented, though, as a bloc: there are, for instance, three separate far-right groupings in the European Parliament, which means that their influence there is limited.

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

Democrats push for ICE accountability

Democrats push for ICE accountabilityFeature U.S. citizens shot and violently detained by immigration agents testify at Capitol Hill hearing

-

Fulton County: A dress rehearsal for election theft?

Fulton County: A dress rehearsal for election theft?Feature Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard is Trump's de facto ‘voter fraud’ czar

-

‘Melania’: A film about nothing

‘Melania’: A film about nothingFeature Not telling all

-

Greenland: The lasting damage of Trump’s tantrum

Greenland: The lasting damage of Trump’s tantrumFeature His desire for Greenland has seemingly faded away

-

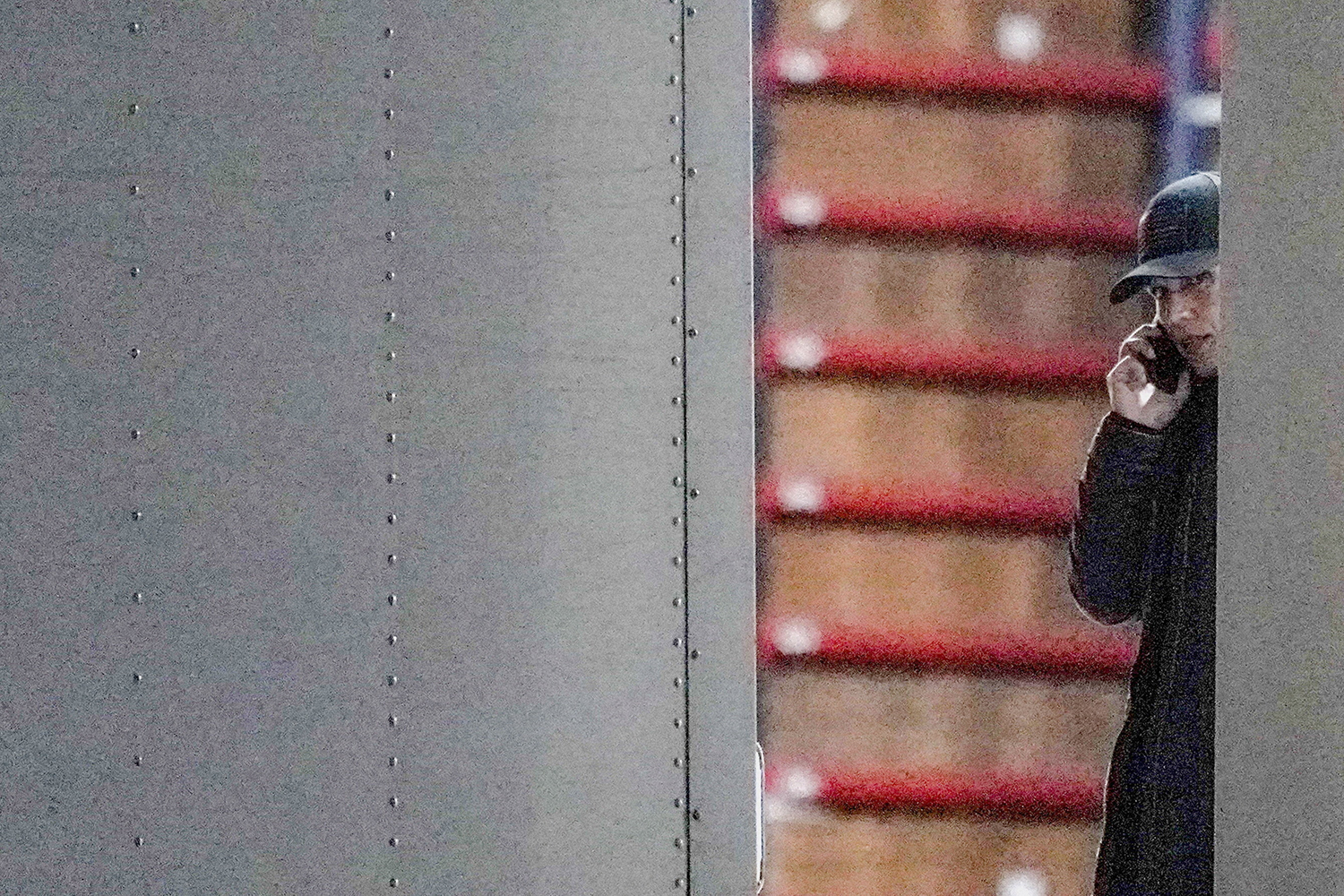

Minneapolis: The power of a boy’s photo

Minneapolis: The power of a boy’s photoFeature An image of Liam Conejo Ramos being detained lit up social media

-

The price of forgiveness

The price of forgivenessFeature Trump’s unprecedented use of pardons has turned clemency into a big business.

-

Reforming the House of Lords

Reforming the House of LordsThe Explainer Keir Starmer’s government regards reform of the House of Lords as ‘long overdue and essential’

-

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?Talking Point Rambling speeches, wind turbine obsession, and an ‘unhinged’ letter to Norway’s prime minister have caused concern whether the rest of his term is ‘sustainable’