The Day After, all over again

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

On Nov. 20, 1983, my hometown was devastated by a nuclear attack and just about everybody watched.

Lawrence, Kansas, was the setting of The Day After, an all-star TV movie that depicted nuclear war between the United States and the Soviet Union, along with its terrible aftermath in an all-too-typical Midwestern community. Hundreds of my city's residents dressed up as injured blast survivors to play extras. Viewers watched Jason Robards survive the blast, only to slowly succumb to sickness from the radioactive fallout. The film ends with John Lithgow calling plaintively on a radio to the outside world, getting no answer.

It was terrifying.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The Day After was also hugely influential. More than 38 million households tuned into the broadcast, one of the largest television audiences of all time. President Ronald Reagan screened the movie at Camp David, then wrote in his diary that it left him "greatly depressed." Henry Kissinger, William F. Buckley, and Secretary of State George Shultz went on TV to debate nuclear weapons. Many of the rest of us were left with a seemingly permanent sense of dread. By the early 1980s, the era of "duck and cover" had long since passed — the expectation was that an actual nuclear war would amount to Armageddon, the end of humanity itself. The Day After "was a piercing wake-up shriek," the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists later observed.

One of the best things about the end of the Cold War was that all that dread receded into the background. Yes, the U.S. and Russia still had enough weapons to effectively set the entire planet on fire — but without the everyday possibility of armed conflict, it just didn't seem that likely.

Now the dread is real again, and rising.

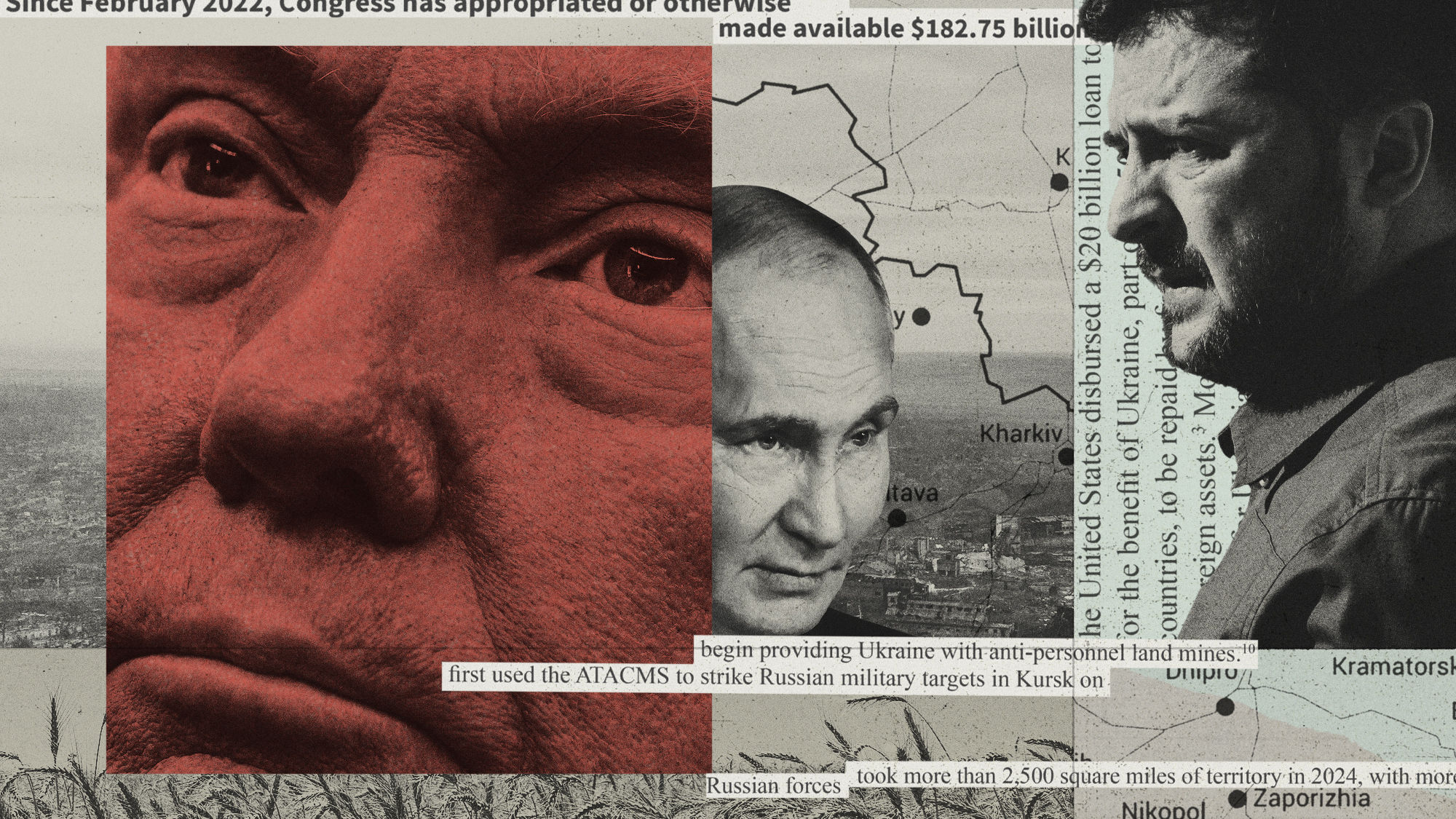

The possibility of nuclear war undergirds the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the world's response to it. President Biden keeps telling us that no U.S. troops will be sent to defend Ukraine because the possibility of getting into a fight with another state armed with atomic bombs is too much to risk. Vladimir Putin all but explicitly threatened that possibility Wednesday night, warning that countries that interfere with his invasion will suffer "consequences you have never faced in your history." Jean-Yves Le Drian, the French foreign minister, felt free to push back: "Yes, I think that Vladimir Putin must also understand that the Atlantic alliance is a nuclear alliance," he said Thursday. "That is all I will say about this."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Just to underline the point, Russian troops reportedly seized the former Chernobyl nuclear plant during their early attacks.

Even now, for many of us, there is a sense that what is happening is happening over there. But The Day After remains a reminder that in a world where missiles can carry unthinkable destruction around the world within minutes, that's not entirely true. You don't have to be directly threatened by the violence in Ukraine to fear what might happen next.

Joel Mathis is a writer with 30 years of newspaper and online journalism experience. His work also regularly appears in National Geographic and The Kansas City Star. His awards include best online commentary at the Online News Association and (twice) at the City and Regional Magazine Association.

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

The mission to demine Ukraine

The mission to demine UkraineThe Explainer An estimated quarter of the nation – an area the size of England – is contaminated with landmines and unexploded shells from the war

-

The secret lives of Russian saboteurs

The secret lives of Russian saboteursUnder The Radar Moscow is recruiting criminal agents to sow chaos and fear among its enemies

-

Is the 'coalition of the willing' going to work?

Is the 'coalition of the willing' going to work?Today's Big Question PM's proposal for UK/French-led peacekeeping force in Ukraine provokes 'hostility' in Moscow and 'derision' in Washington

-

Ukraine: where do Trump's loyalties really lie?

Ukraine: where do Trump's loyalties really lie?Today's Big Question 'Extraordinary pivot' by US president – driven by personal, ideological and strategic factors – has 'upended decades of hawkish foreign policy toward Russia'

-

What will Trump-Putin Ukraine peace deal look like?

What will Trump-Putin Ukraine peace deal look like?Today's Big Question US president 'blindsides' European and UK leaders, indicating Ukraine must concede seized territory and forget about Nato membership

-

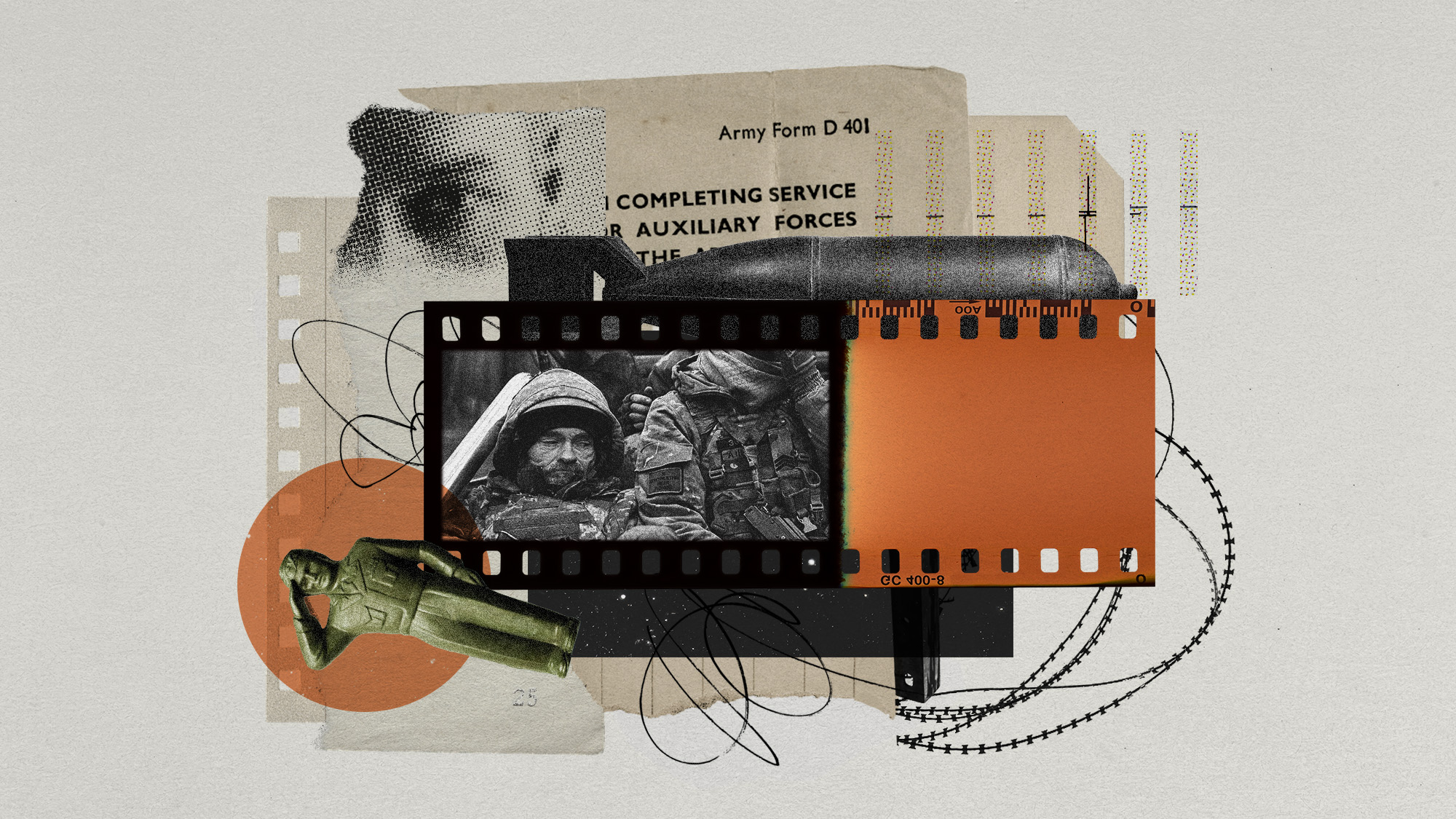

Ukraine's disappearing army

Ukraine's disappearing armyUnder the Radar Every day unwilling conscripts and disillusioned veterans are fleeing the front

-

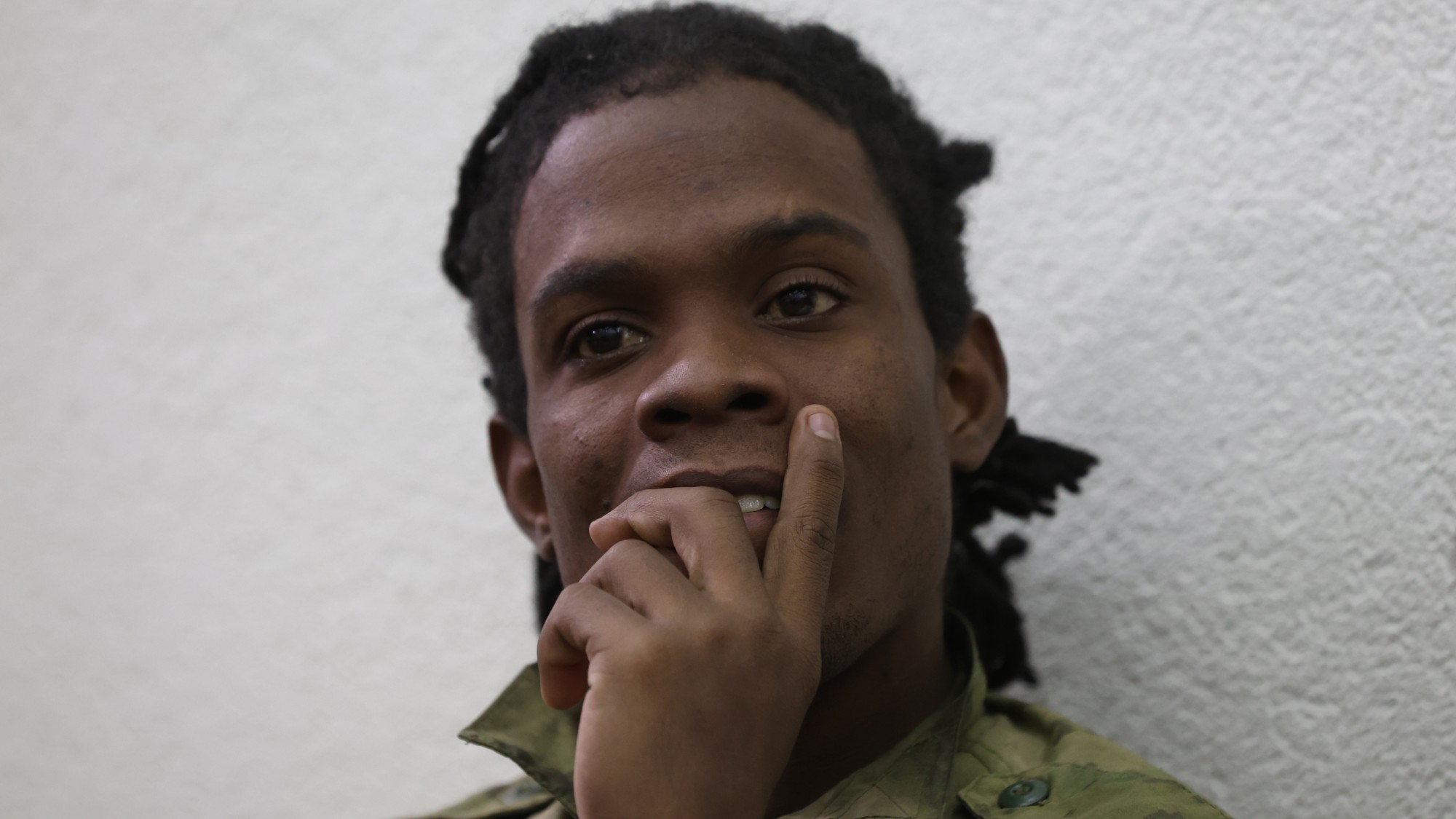

Cuba's mercenaries fighting against Ukraine

Cuba's mercenaries fighting against UkraineThe Explainer Young men lured by high salaries and Russian citizenship to enlist for a year are now trapped on front lines of war indefinitely

-

Ukraine-Russia: are both sides readying for nuclear war?

Ukraine-Russia: are both sides readying for nuclear war?Today's Big Question Putin changes doctrine to lower threshold for atomic weapons after Ukraine strikes with Western missiles