A brief history of the modern Olympics – and the winner's curse

Paris 2024 will be the 30th instalment of the summer Games

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The first Olympic Games are traditionally dated to 776BC. Games were held all over ancient Greece; but the most famous were held every four years in the sanctuary at Olympia, in the Peloponnese, as part of a religious festival in honour of Zeus.

These Games attracted crowds of tens of thousands, who gathered to watch athletes compete in events such as running, boxing, discus, long jump and pentathlon; to pay homage at the giant gold and ivory statue of Zeus; and to witness the ritual sacrifice of 100 oxen. Athletes would compete, mostly in the nude, for the chance to win a wreath of leaves and to receive a hero's welcome on their return home.

But the Games' popularity waned after Greece was conquered by Rome in the 2nd century BC. They ended around AD394, when Theodosius I outlawed pagan celebrations, and weren't held again for another 1,503 years.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How did the modern Games come about?

The word "Olympics'' started to be used again for sporting events in England in the Renaissance: the Cotswold Olimpicks were held near Chipping Campden from the early 1600s; the Wenlock Olympian Games, at Much Wenlock in Shropshire, began in 1850. The modern Olympics were the brainchild of Baron Pierre de Coubertin, a Hellenophile French educator and historian with a strong belief in the power of sport to form character and to promote peace between nations; he was greatly inspired by the sporting theme in Thomas Hughes's 1857 novel Tom Brown's School Days, and by the Much Wenlock Games, which he visited in 1890. In 1892, de Coubertin proposed reviving the Olympics in Paris, initially with little success. But his efforts led to the formation of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) in 1894, and to the first modern Games, in Athens in 1896.

What were the early Games like?

The Athens Games were small – 241 athletes from 14 countries competed – and somewhat chaotic. An Irishman named John Pius Boland won gold in the men's singles tennis having entered on an impulse while on holiday.

The next two Games, in Paris in 1900 and in St Louis in 1904, were also fairly minor events: effectively sideshows of, respectively, the World Exhibition and the World Fair. The 1908 London Games were the first in which the modern Olympics began recognisably to emerge. A large stadium was built at White City, and athletes joined an opening ceremony parade behind their national flags for the first time. Crowds of nearly 70,000 watched 110 events in 25 sporting disciplines.

How did the Olympics develop?

They gathered pace, with innovations such as the photo finish (Stockholm, 1912) and the athletes' village (Paris, 1924). There were no Games during the First World War, but the 1920 Antwerp Olympics saw the rings logo, designed by Coubertin to reflect the five continents, used for the first time.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The first Winter Olympics were held at Chamonix in 1924. The Olympic flame first appeared in Amsterdam in 1928, and the podium four years later. But, arguably, the Berlin Olympics in 1936, with its display of Nazi pomp and grandeur, did much to give the Games the status they have today. The torch relay is a tradition invented for Berlin: it was welcomed by 29,000 members of the Hitler Youth, on a seven-mile avenue bedecked with giant swastikas and guarded by 40,000 stormtroopers. Berlin was a major propaganda success for Hitler, although his efforts to advertise the supremacy of the Aryan race were undermined by the African-American sprinter Jesse Owens, who won four gold medals. In 1948, the Paralympics were born at Stoke Mandeville spinal injury hospital in Buckinghamshire.

Were the Games always political?

In theory, no: the Olympics' unofficial mantra is "politics and sport don't mix". But, in practice, they often do. In Mexico City in 1968, ten days before the opening ceremony, hundreds of leftwing protesters were killed by the army. The same year, two African-American athletes, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, gave a Black Power salute on the podium. At Munich in 1972, West Germany's attempts to show a new face to the world ended in tragedy, when 11 Israeli athletes were taken hostage and killed by Palestinian terrorists.

The Olympics were a forum for Cold War rivalries. From the 1960s until 1989, East Germany ran a huge doping operation, designed to establish communism's superiority. In 1980, the US led more than 60 countries in a boycott of the Moscow Games in protest at the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Four years later, the USSR led 12 other eastern bloc states (and Cuba) in a boycott of the Los Angeles Games.

What about the business side?

The arrival of TV in the 1960s heralded a new era of corporate sponsorship; and since the 1980s, professional athletes have been allowed to compete – a departure from de Coubertin's vision of the Games as an amateur affair. At times, commercialisation has threatened their integrity: the huge role of Coca-Cola at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics raised eyebrows. Today, money remains a vexed issue. TV rights are worth some $3bn, and sponsorship over $1bn. Host cities, though, pay a high price.

What about the sport?

The number of sports and athletes represented has ballooned: the Tokyo 2020 Games brought 11,479 sportspeople from 206 countries, competing in 50 disciplines, from the 100 metres to surfing to softball and golf. The Olympics have always provided electrifying spectacles, from Bob Beamon's long jump in 1968, to gymnast Nadia Comaneci's perfect ten at Montreal in 1976, to Usain Bolt's record-breaking sprints at Beijing 2008, to Mo Farah's triumphs at London 2012. Whatever criticisms they attract, the Olympics always capture the world's imagination.

What is the winner's curse?

Hosting the Games is eye-wateringly expensive. The London Olympics in 2012 cost $17bn, the Rio Games in 2016 $20bn (and led to 60,000 people being displaced from their homes). The main costs are the creation or upgrading of stadiums, and facilities for sports such as cycling and swimming, as well as extra housing and transport infrastructure. The legacy is often a series of white elephants. Sydney's stadium costs $30m a year to maintain. The $3bn costs of Athens 2004 contributed to the country's debt crisis; almost all the facilities built for it are now derelict.

These problems – known as the "winner's curse" – have a long history. Debts from the 1976 Montreal Olympics were only paid off in 2006. Revenues do not cover spending: Tokyo made $5.8bn in 2020, but spent $13bn. The IOC keeps most TV and sponsorship money (it spends 90% of that supporting athletes, the Games and the "Olympic movement"). The idea is that the Games provide a long-term lift to the economy, tourism and jobs – and to participation in sport. The evidence says otherwise, with the exception of Barcelona in 1992. The IOC has tried to drive down costs; Paris's budget is relatively small: $8bn. Critics say they should come down further, or that the Games should be held in one city in perpetuity.

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

The price of sporting glory

The price of sporting gloryFeature The Milan-Cortina Winter Olympics kicked off this week. Will Italy regret playing host?

-

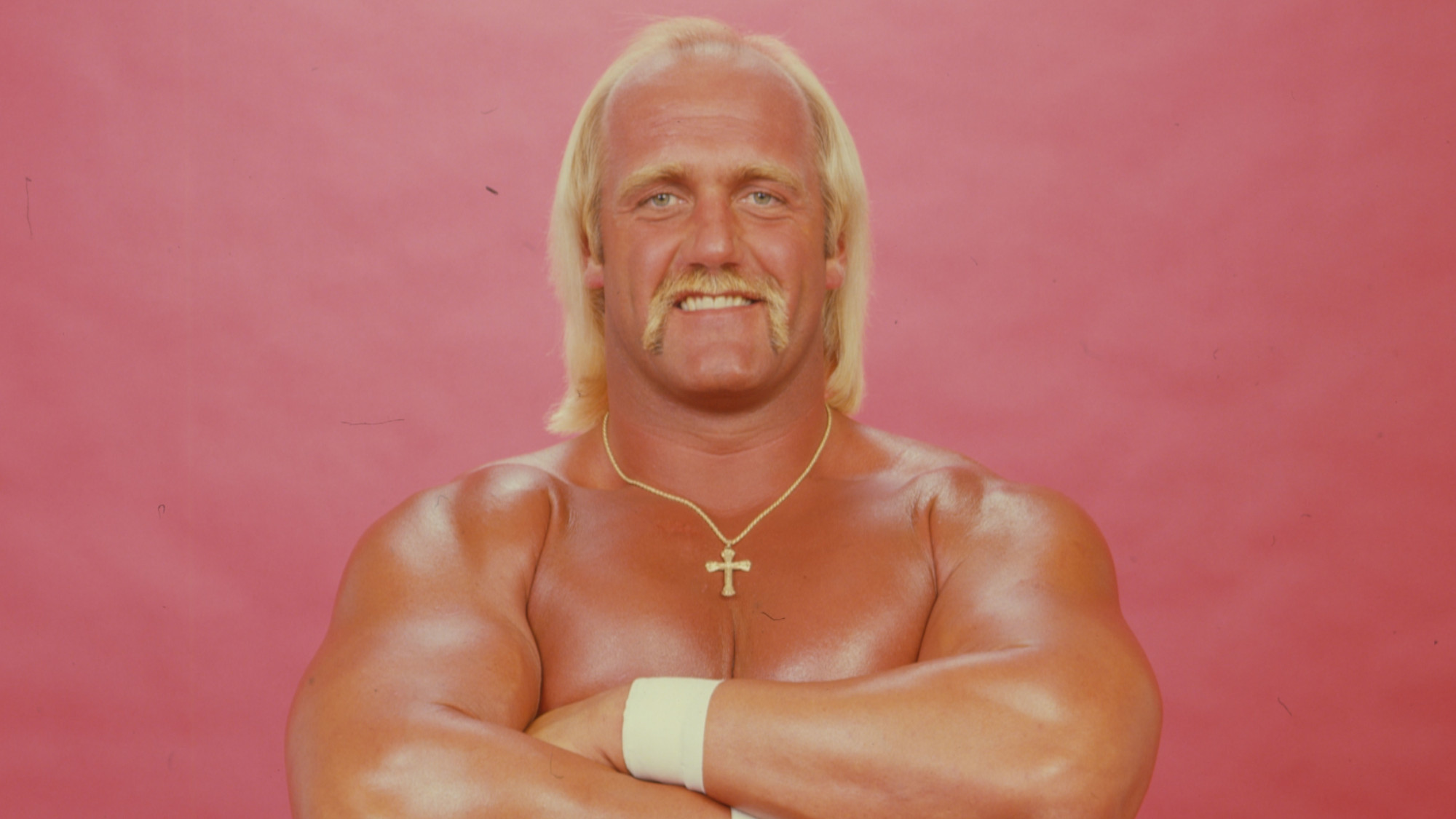

Hulk Hogan

Hulk HoganFeature The pro wrestler who turned heel in art and life

-

Kirsty Coventry: the former Olympian and first woman to lead the IOC

Kirsty Coventry: the former Olympian and first woman to lead the IOCIn the Spotlight Coventry, a former competitive swimmer, won two Olympic gold medals

-

Have the Rockies reached a breaking point?

Have the Rockies reached a breaking point?the explainer Baseball's most aimless franchise takes aim at a record set just last year

-

Cricket's crackdown on 'monster' bats

Cricket's crackdown on 'monster' batsIn the Spotlight Indian Premier League has introduced on-pitch checks to ensure bats meet strict size limits

-

The Masters: Rory McIlroy finally banishes his demons

The Masters: Rory McIlroy finally banishes his demonsIn the Spotlight McIlroy's grand slam triumph will go down as 'one of the greatest and most courageous victories in the history of golf'

-

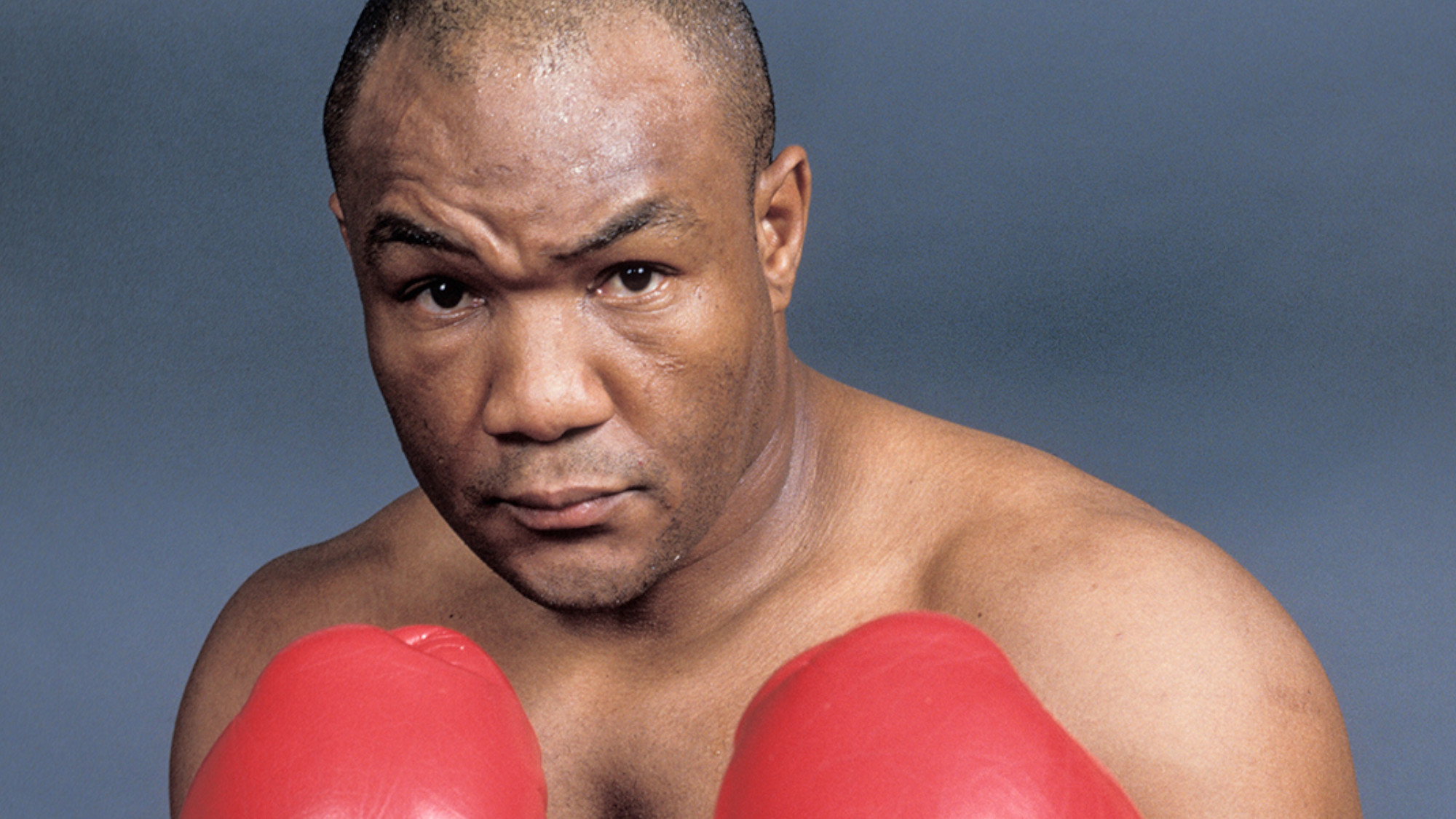

George Foreman: The boxing champ who reinvented home grills

George Foreman: The boxing champ who reinvented home grillsFeature He helped define boxing’s golden era