Why everybody’s talking about the public inquiry into undercover policing

Long-delayed investigation into abuses by ‘spycops’ is one of the most complicated in British legal history

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A major inquiry into undercover policing in the UK has finally begun almost six years after being announced by then home secretary Theresa May.

The Undercover Policing Inquiry (UCPI) is “one of the most complicated, expensive and delayed public inquiries in British legal history”, the BBC reports. The investigation centres on allegations of systematic abuses by so-called spycops that date back more than four decades.

Why was the inquiry launched?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The UCPI was established in early 2015 in response to a series of allegations that May said amounted to evidence of “historical failings” by undercover policing units. Among these allegations were that the parents of murdered black teenager Stephen Lawrence had been spied on while campaigning for justice - claims that the police admitted were true.

After finally getting under way in London last week, the jury-led inquiry is looking at how at least “139 undercover officers spied on more than 1,000 political groups” over a period spanning back to 1968, writes investigative reporter Rob Evans, author of Undercover: The True Story of Britain’s Secret Police.

Two undercover units are at the heart of the inquiry: the Metropolitan Police’s Special Demonstration Squad (SDS), which worked in London, and the National Public Order Intelligence Unit (NPOIU) which operated across the UK. Both units have since been disbanded.

The inquiry, which is expected to continue for at least three years, is focusing first on the SDS.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The group was put together in the late 1960s amid protests over the Vietnam War, in response to “official concerns that public anger over the issue and unrest in Europe, particularly in Paris, signalled that far-left groups in England and Wales were planning disorder on home soil”, says The Independent.

“At first, officers were deployed undercover for weeks or months,” says the newspaper, but as the unit extended its investigations to infiltrate a long list organisations and trade unions, some of these assignments lasted for years.

The inquiry to expected to hear evidence from more than 200 witnesses, including politicians and Whitehall officials who oversaw the undercover operations.

Thousands of confidential documents that police “assumed would never see the light of day” are also due to be published, The Guardian reports. “However, one large tranche of documents, which may have shed light on operations since the 1990s, will not be released because it was recently destroyed by police.”

Policing the bedroom

One of the most sensitive issues to be explored by the inquiry are allegations that multiple undercover police officers deceived women into sexual relationships while using fake identities. One undercover officer, Bob Lambert, fathered a child with his unwitting partner, an animal rights campaigner, before disappearing from their lives when his deployment ended in the late 1980s.

The Independent’s home affairs correspondent Lizzie Dearden quotes a woman named only as Lisa, to protect her identity, describing how another spycop - Mark Kennedy - was “put in my life deliberately to deceive me”.

“Over 30 women have found they were also in relationships with people who didn’t exist,” Lisa added.

These cases date back to the 1970s and suggest that the “targeting of women may have been considered a justified means for officers to embed themselves deep into the movements they were targeting”, says the BBC.

In 2015, the Metropolitan Police issued an “unreserved apology” and paid compensation to seven women who had been deceived into relationships.

But many more are still waiting for justice - and other women have also suffered. Last week, a statement was made to the inquiry on behalf of three women who “believed they were making personal sacrifices” so their police officer husbands could go undercover to infiltrate political groups during long-term deployments.

“Those women fulfilled their role dutifully, towards both their husbands and the honourable causes they believed they were serving – the fight against crime, terror and violence,” the statement read.

“These sacrifices came with a heavy price for their own lives and their families, and they believed they were making them for all of us, the public.”

Spy games

Another major issue being tackled by the inquiry is the police’s use of undercover officers to infiltrate political groups, as well as intensive surveillance of private citizens.

Particular focus is being placed on how officers “circled” the family of murdered teenager Lawrence, “looking to smear them instead of catching their son’s killers”, the Daily Mail says.

The inquiry has heard that the family “were not terrorists, criminals or any threat to public order” and that there was “no conceivable justification” for the snooping.

A statement prepared by Imran Khan QC on behalf of Lawrence’s mother said that the family is “losing confidence” in “this inquiry’s ability to get to the truth”.

Another spying victim in the spotlight is left-wing writer and public intellectual Tariq Ali, who was monitored by at least 14 undercover police officers due to his anti-war campaigning.

“Previously secret reports disclosed how police spied on Ali as he helped promote political campaigns against the Vietnam War, violent racist assaults, fascism and other progressive causes,” investigative reporter Evans writes in The Guardian. Ali told the inquiry that “grotesque” police reports detailing such operations showed the spying network was “utterly out of control”.

Are the undercover operations still happening?

The Metropolitan Police has “repeatedly sought to paint the scandal as largely historical, and has never been drawn on whether such operations continue”, Evans reports.

The retired judge leading the inquiry, John Mitting, last week demanded to know whether the force is currently infiltrating political groups or helping the MI5 to monitor people considered to be subversives.

But Met Police barrister Peter Skelton failed to answer the question, simply saying that his opening statement had not been intended to “imply anything about the scope of the Metropolitan Police’s present undercover work”.

In response, Mitting warned that “they are questions that in due course I will want to be answered”.

-

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’The Week Recommends Mystery-comedy from the creator of Derry Girls should be ‘your new binge-watch’

-

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960s

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960sThe standout shows of this decade take viewers from outer space to the Wild West

-

Microdramas are booming

Microdramas are boomingUnder the radar Scroll to watch a whole movie

-

Why have homicide rates reportedly plummeted in the last year?

Why have homicide rates reportedly plummeted in the last year?Today’s Big Question There could be more to the story than politics

-

How the ‘British FBI’ will work

How the ‘British FBI’ will workThe Explainer New National Police Service to focus on fighting terrorism, fraud and organised crime, freeing up local forces to tackle everyday offences

-

‘Stakeknife’: MI5’s man inside the IRA

‘Stakeknife’: MI5’s man inside the IRAThe Explainer Freddie Scappaticci, implicated in 14 murders and 15 abductions during the Troubles, ‘probably cost more lives than he saved’, investigation claims

-

3 officers killed in Pennsylvania shooting

3 officers killed in Pennsylvania shootingSpeed Read Police did not share the identities of the officers or the slain suspect, nor the motive or the focus of the still-active investigation

-

Christian Brückner: why prime suspect in Madeleine McCann case can refuse Met interview

Christian Brückner: why prime suspect in Madeleine McCann case can refuse Met interviewThe Explainer International letter of request rejected by 49-year-old convicted rapist as he prepares to walk free

-

Dash: the UK's 'flawed' domestic violence tool

Dash: the UK's 'flawed' domestic violence toolThe Explainer Risk-assessment checklist relied on by police and social services deemed unfit for frontline use

-

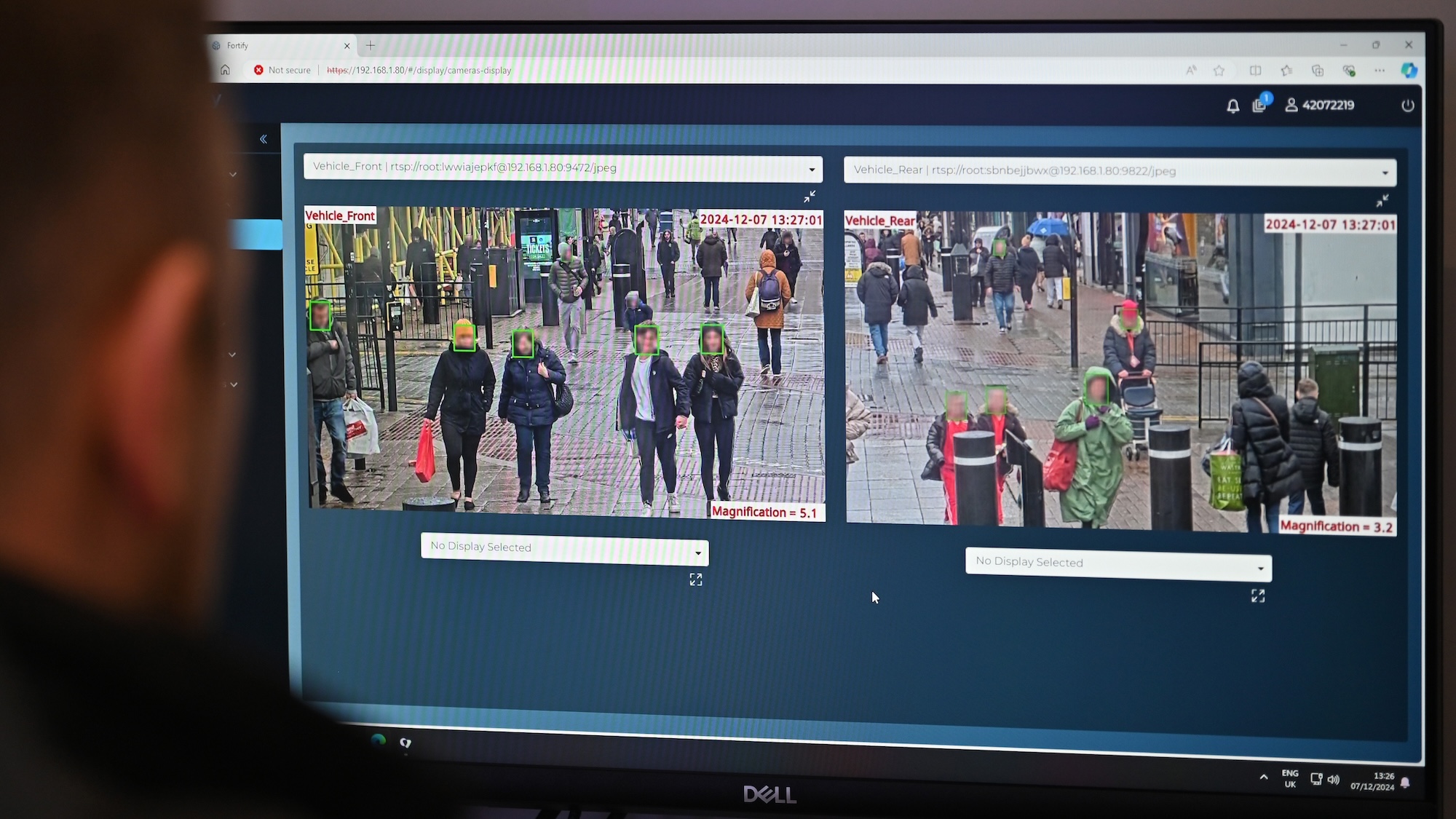

The ethics behind facial recognition vans and policing

The ethics behind facial recognition vans and policingThe Explainer The government is rolling out more live facial recognition technology across England

-

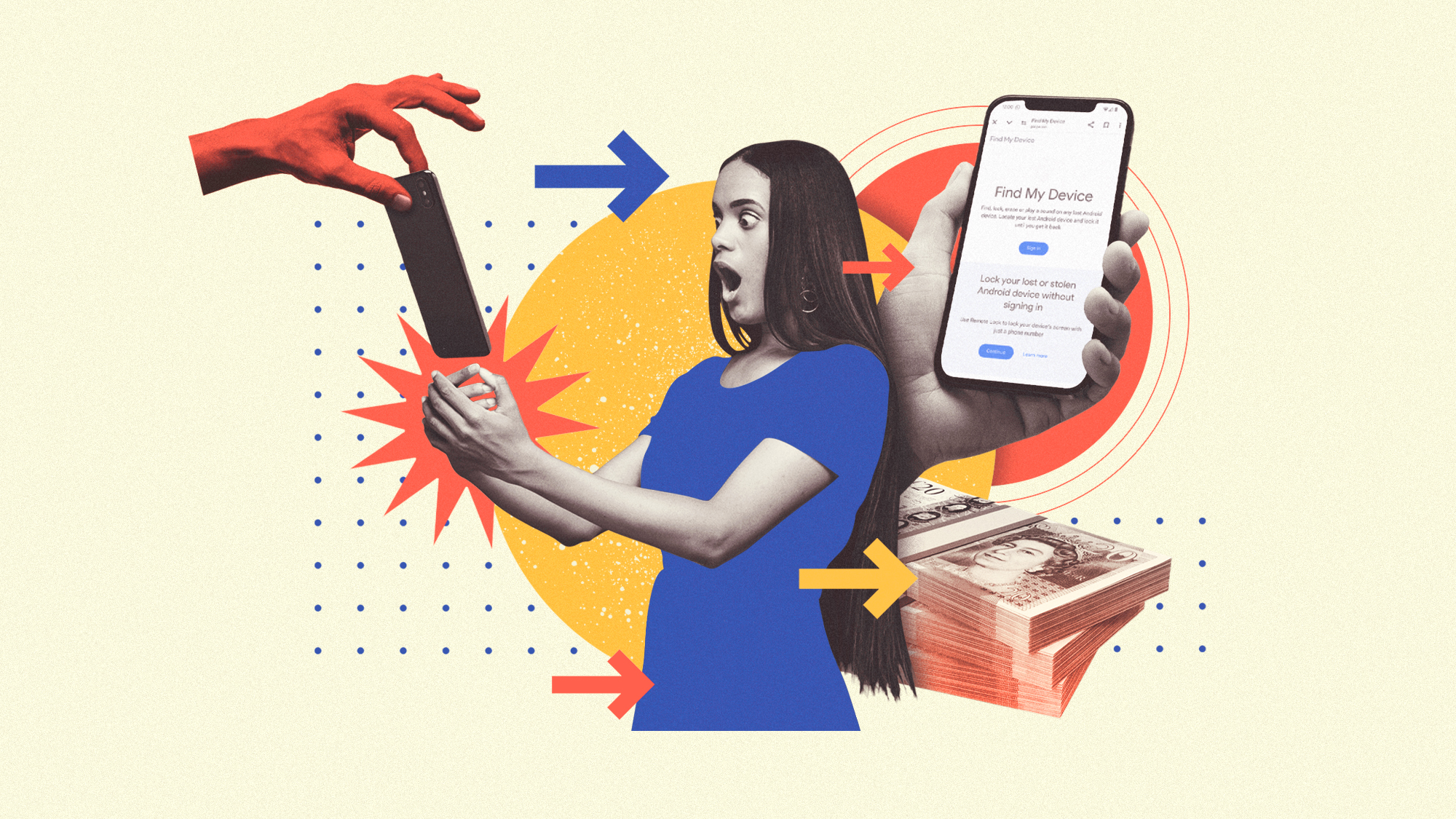

What to do if your phone is stolen

What to do if your phone is stolenThe Explainer An average of 180 phones is stolen every day in London, the 'phone-snatching capital of Europe'