Superyachts are getting caught up in spy scandals

China and Russia have both been accused of spying maneuvers on the open sea

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Even the rich and powerful may not be safe from the world of international espionage, as recent reports have alleged that countries are using multimillion-dollar superyachts in spy operations. And at least one country, China, has reportedly been spying on the superyacht manufacturers themselves.

Wealthy oligarchs have long been both targets and tools of espionage, especially from authoritarian states. But the apparent superyacht spy tie-in marks a new chapter in this saga.

How are superyachts connected with spying?

Most notable is Russia, which is reportedly "using its unrivaled underwater warfare capabilities to map, hack and potentially sabotage critical British infrastructure," said The Sunday Times. Much of this seems to involve the use of superyachts for surveillance. Before Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, there was "credible intelligence that superyachts owned by oligarchs may have been used to conduct underwater reconnaissance around Britain."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

This is noteworthy given that many of these oligarchs' yachts have moon pools, which are openings in the bottom of a ship's hull that can be "used covertly to deploy and retrieve deep-sea reconnaissance and diving equipment," said the Times. This type of surveillance is said to go back even before Russia's invasion of Ukraine. In 2018, the British ship HMS Albion had been "docked for under 24 hours when a huge superyacht belonging to an oligarch pulled up alongside it" in Cyprus. British Navy officials suspected the yacht was there "covertly to surveil the Albion."

Beyond the yachts themselves, Chinese officials may be spying on superyacht manufacturers, in particular luxury shipbuilder Ferretti SpA, according to a Bloomberg report. In 2024, the "relationship between senior managers at Ferretti — one of the world's leading designers of yachts for the super-rich — and its biggest shareholder," the Chinese conglomerate Weichai group, had "soured over a share-buyback program."

As this continued, Ferretti's "executive director, Xu Xinyu, discovered he was being followed and found surveillance devices in the company's Milan offices," said Bloomberg. Similar devices were reportedly also found in the offices of Ferretti's board secretary and Chinese-Italian translator. This eventually led to a "spy-vs.-spy scenario" where Xu saw people "following him while visiting hotels" in Milan, said Robb Report.

How are other countries fighting back?

Countries are working to minimize the impact of superyachts that may be compromised by spying. Alongside NATO and other European allies, the U.K. is "strengthening our response to ensure that Russian ships and aircraft cannot operate in secrecy near the U.K. or near NATO territory," a spokesperson for the British Defense Ministry told Newsweek.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The U.K. is "committed to enhancing the security of critical offshore infrastructure," the spokesperson told Newsweek, noting that the defense ministry was also using AI to "detect and minimize threats to undersea infrastructure." This includes the type of undersea spying outlined in the yacht allegations.

Some outlets have also highlighted ways that superyacht owners can protect their vessels from intrusions. This includes installing a sonar system that "detects, tracks and identifies divers and underwater vehicles approaching a superyacht," said Forbes, as well as an anti-drone device that "detects and identifies commercial drones." While these types of devices are "being used to deter pirates" in international waters, they may also act as a deterrent for spies.

Justin Klawans has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022. He began his career covering local news before joining Newsweek as a breaking news reporter, where he wrote about politics, national and global affairs, business, crime, sports, film, television and other news. Justin has also freelanced for outlets including Collider and United Press International.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Alexei Navalny and Russia’s history of poisonings

Alexei Navalny and Russia’s history of poisoningsThe Explainer ‘Precise’ and ‘deniable’, the Kremlin’s use of poison to silence critics has become a ’geopolitical signature flourish’

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions

-

US, Russia restart military dialogue as treaty ends

US, Russia restart military dialogue as treaty endsSpeed Read New START was the last remaining nuclear arms treaty between the countries

-

What happens now that the US-Russia nuclear treaty is expiring?

What happens now that the US-Russia nuclear treaty is expiring?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION Weapons experts worry that the end of the New START treaty marks the beginning of a 21st-century atomic arms race

-

EU and India clinch trade pact amid US tariff war

EU and India clinch trade pact amid US tariff warSpeed Read The agreement will slash tariffs on most goods over the next decade

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

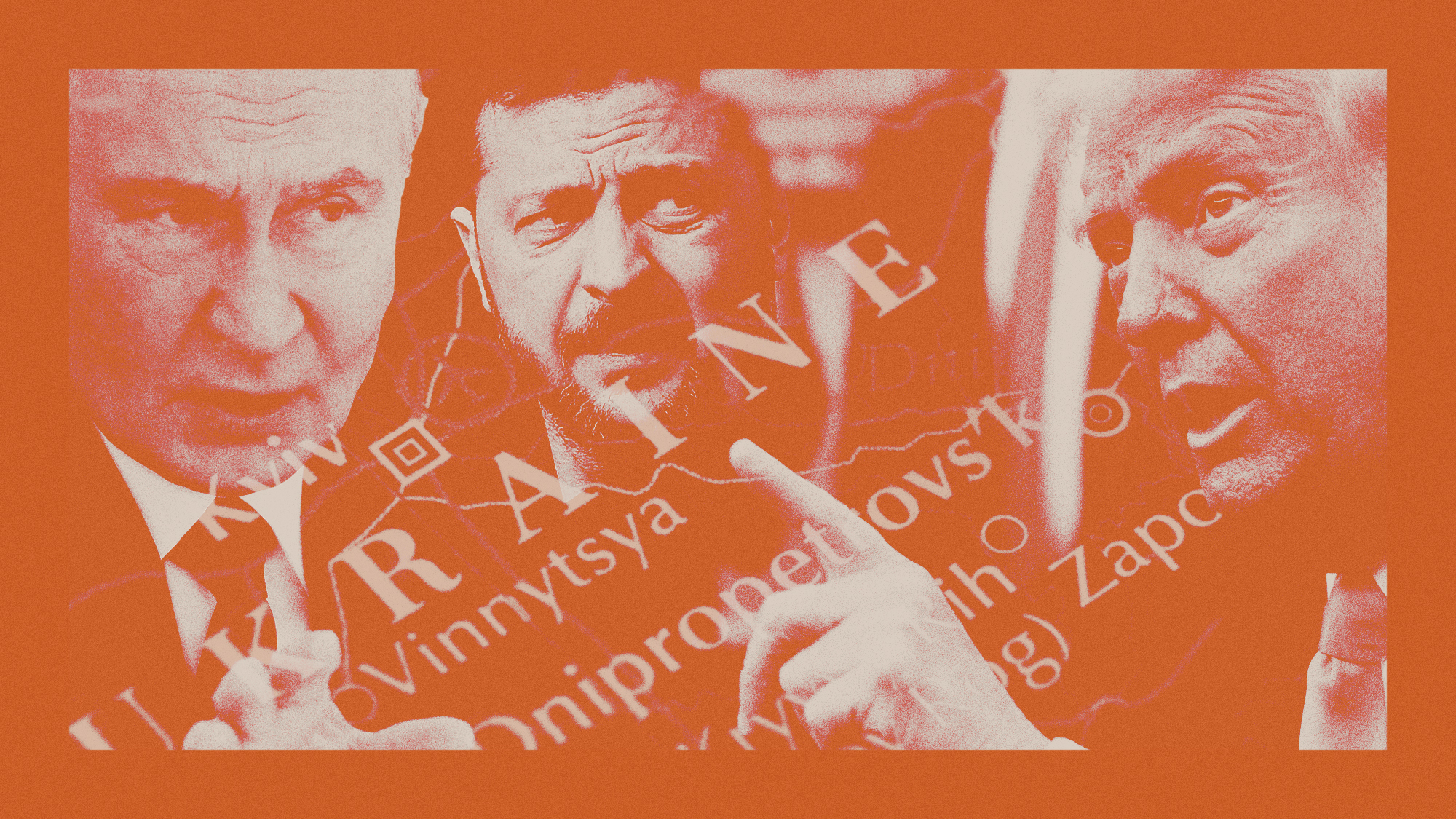

Ukraine, US and Russia: do rare trilateral talks mean peace is possible?

Ukraine, US and Russia: do rare trilateral talks mean peace is possible?Rush to meet signals potential agreement but scepticism of Russian motives remain

-

The rise of the spymaster: a ‘tectonic shift’ in Ukraine’s politics

The rise of the spymaster: a ‘tectonic shift’ in Ukraine’s politicsIn the Spotlight President Zelenskyy’s new chief of staff, former head of military intelligence Kyrylo Budanov, is widely viewed as a potential successor