Bowing to Beijing

Out of fear of losing access to the huge Chinese market, Hollywood film studios are censoring themselves

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Out of fear of losing access to the huge Chinese market, Hollywood film studios are censoring themselves. Here's everything you need to know:

Why is there tension?

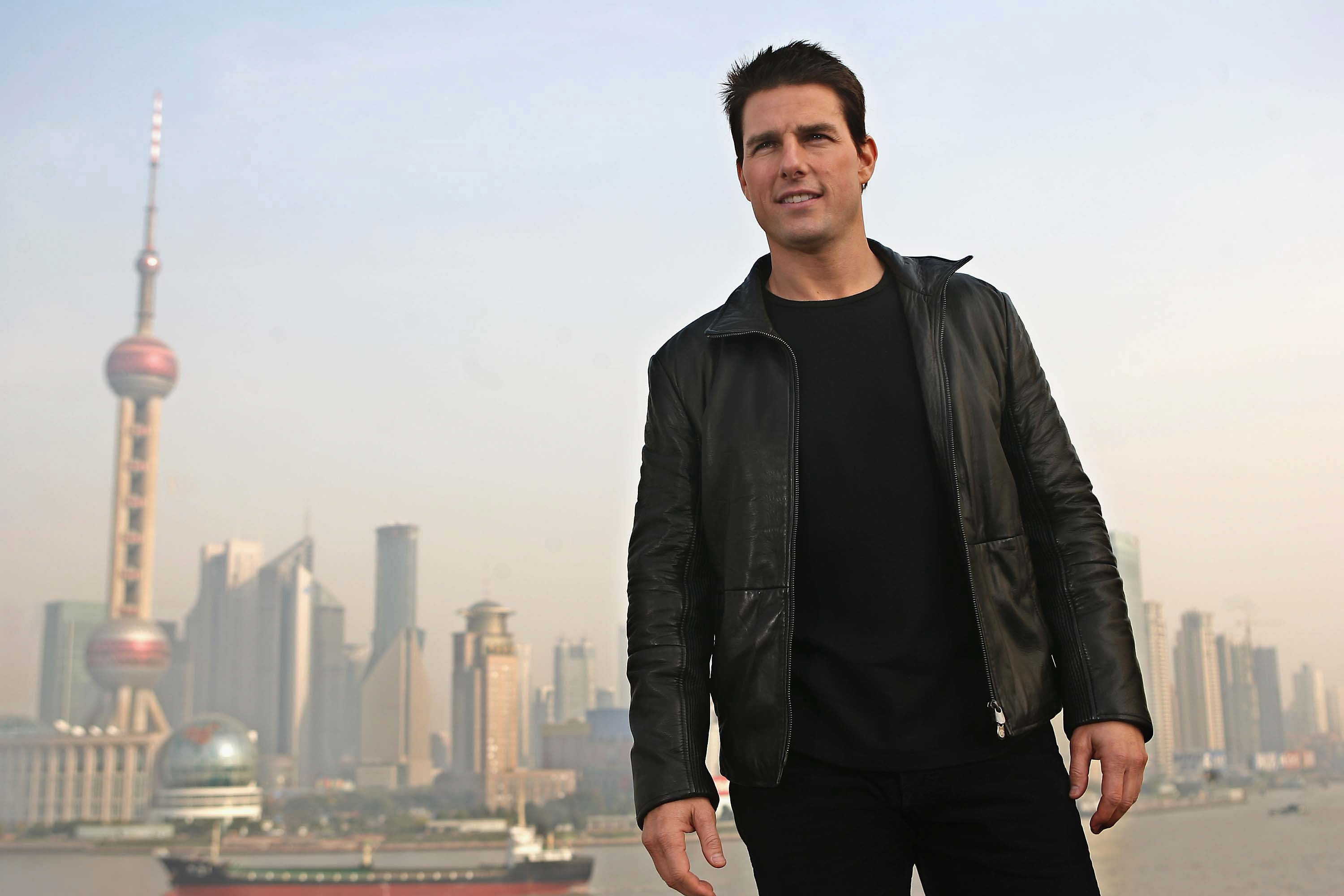

Hollywood is under fire from all sides for capitulating to the Chinese government, which demands that all foreign films meet its ideological standards. John Cena, who stars in the ninth Fast and Furious action car-chase series, recently apologized to Chinese fans after referring to Taiwan as a country in a promotional video. China considers Taiwan a breakaway province that will inevitably come under its control. "I'm very sorry for my mistakes," Cena groveled, while speaking in Mandarin. "Sorry. Sorry. I'm really sorry." Fans of the original Top Gun have noticed that in the upcoming sequel, the flag of Taiwan that was on Tom Cruise's jacket has disappeared. And in the credits of its 2020 live-action Mulan remake, Disney thanked local officials in Xinjiang, where China runs brutal "re-education" camps for Uighur Muslims and has been accused of genocide. "Instead of us doing business with China and that leading to China being more free," said director Judd Apatow, "what has happened is that China has bought our silence with their money."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

When did this begin?

China began opening its cinemas to overseas movies in the mid-1990s, creating a huge financial opportunity for American studios willing to play by the rules. In 1997, Disney released Martin Scorsese's Kundun, a biopic of the 14th and current Dalai Lama that depicts China's 1950 invasion and annexation of Tibet and the Dalai Lama's subsequent exile in India. Chinese officials, who claim they "liberated" Tibet, were infuriated. Disney boss Michael Eisner harbored dreams of opening theme parks in Hong Kong and Shanghai, so he enlisted Richard Nixon's onetime China emissary Henry Kissinger to smooth tensions. Eisner also personally apologized to Chinese officials, calling the release of Kundun a "stupid mistake." Eisner got his theme parks, and Disney returned to Chinese cinemas in 1999 with the animated and inoffensive Mulan. Scorsese's films, meanwhile, were banned from China for more than a decade. Hollywood has tiptoed carefully around sensitive topics ever since.

How are films being altered?

In a report last year, "Made in Hollywood, Censored by Beijing," the free-speech organization PEN America accused industry decision-makers of changing "the content, casting, plot, dialogue, and settings" of films "to avoid antagonizing Chinese officials." At first, studios only tweaked their Chinese releases — for example, when censors ordered that dirty laundry be removed from Shanghai balconies in Mission: Impossible 3. But soon studios began removing potential sore points from their U.S. releases. The 2012 remake of Red Dawn originally depicted a Chinese invading army, but so as not to offend Beijing, they were digitally altered to become North Korean troops in both the U.S. and Chinese releases. China's government allows only 34 foreign films to be released each year, and studios competing for those valuable slots fear being denied access to 1.4 billion people — the world's largest box-office market. "Over time, writers and creators don't even conceive of ideas, stories, or characters that would flout the rules, because there is no point in doing so," the PEN report said.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What else are studios doing?

To appeal to Chinese audiences, Hollywood has shoehorned popular Chinese actors into films and blatantly placed the popular milk drink Gu Li Duo in the Chinese release of Iron Man 3. In another strategy, studios are co-producing films with Chinese moviemaking houses to evade the foreign-film quota. The Meg, a 2018 thriller about a sharklike dinosaur in modern times, was co-produced by Warner Brothers and a Chinese studio. Jiang Wei, one of its Chinese producers, called the film "suitable" for co-production as "it doesn't involve many cultural, educational, or national issues." Media conglomerate Dalian Wanda sought to buy up American studios before the pandemic in what its founder openly admitted was an effort to wield Chinese "soft power." The company still owns Legendary Entertainment, the California studio behind the upcoming Dune remake. Both Republicans and Democrats have called for legislation to lessen China's influence over Hollywood; a bill introduced by Rep. Mike Gallagher (R-Wis.) would require all Hollywood studios to disclose whether a film has been changed "to fit the demands of the Chinese Communist Party."

Will the bill pass?

Probably not in the immediate future. But despite its efforts to appease Beijing, Hollywood may lose much of its box office in China anyway. Stan-ley Rosen, a political scientist who studies the Hollywood-Beijing relationship, said China's growing film industry is now making so many movies — more than 1,000 in 2019 — that it is squeezing foreign films out of the market. February's Detective Chinatown 3, a Chinese-made heist comedy, pulled in $424 million on its opening weekend in China — the biggest opening of all time in a single market. In 2020, Chinese-made films captured 80 percent of the country's box office, according to the Hollywood Reporter, and all 10 top-grossing films in China last year were made there or in Hong Kong. "China has learned enough from Hollywood to make its own films," Rosen said.

Piracy of U.S.-made films and TV

The Marvel spy thriller Black Widow raked in $215 million on its opening weekend, becoming Hollywood's most successful film of the pandemic era. But despite being approved by censors, the film was not released in China. That's largely because high-quality pirated versions of the film had flooded Chinese file-sharing and streaming sites within hours of its global release. "Even if it is released theatrically later, this will undoubtedly have a significant impact on the box office," one Chinese film blogger pointed out. Many young Chinese became acquainted with the West through pirated popular TV shows, such as Friends, How I Met Your Mother, and Game of Thrones, that volunteers dub with Chinese subtitles. But authorities are cracking down on this unapproved Western culture. Fourteen members of a large streaming firm were arrested in February, and other outfits have disbanded or disappeared since then. Internet users have reacted by sharing the Chinese term lindong jiangzhi — a poetic translation of "winter is coming."

This article was first published in the latest issue of The Week magazine. If you want to read more like it, you can try six risk-free issues of the magazine here.

-

Should the EU and UK join Trump’s board of peace?

Should the EU and UK join Trump’s board of peace?Today's Big Question After rushing to praise the initiative European leaders are now alarmed

-

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problem

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problemThe Explainer Before her appointment as cabinet secretary, commentators said hostile briefings and vetting concerns were evidence of ‘sexist, misogynistic culture’ in No. 10

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

TikTok secures deal to remain in US

TikTok secures deal to remain in USSpeed Read ByteDance will form a US version of the popular video-sharing platform

-

How will China’s $1 trillion trade surplus change the world economy?

How will China’s $1 trillion trade surplus change the world economy?Today’s Big Question Europe may impose its own tariffs

-

Shein in Paris: has the fashion capital surrendered its soul?

Shein in Paris: has the fashion capital surrendered its soul?Talking Point Despite France’s ‘virtuous rhetoric’, the nation is ‘renting out its soul to Chinese algorithms’

-

Will latest Russian sanctions finally break Putin’s resolve?

Will latest Russian sanctions finally break Putin’s resolve?Today's Big Question New restrictions have been described as a ‘punch to the gut of Moscow’s war economy’

-

China’s rare earth controls

China’s rare earth controlsThe Explainer Beijing has shocked Washington with export restrictions on minerals used in most electronics

-

The struggles of Aston Martin: burning cash not rubber

The struggles of Aston Martin: burning cash not rubberIn the Spotlight The car manufacturer, famous for its association with the James Bond franchise, is ‘running out of road’

-

US to take 15% cut of AI chip sales to China

US to take 15% cut of AI chip sales to ChinaSpeed Read Nvidia and AMD will pay the Trump administration 15% of their revenue from selling artificial intelligence chips to China

-

Is Trump's tariffs plan working?

Is Trump's tariffs plan working?Today's Big Question Trump has touted 'victories', but inflation is the 'elephant in the room'