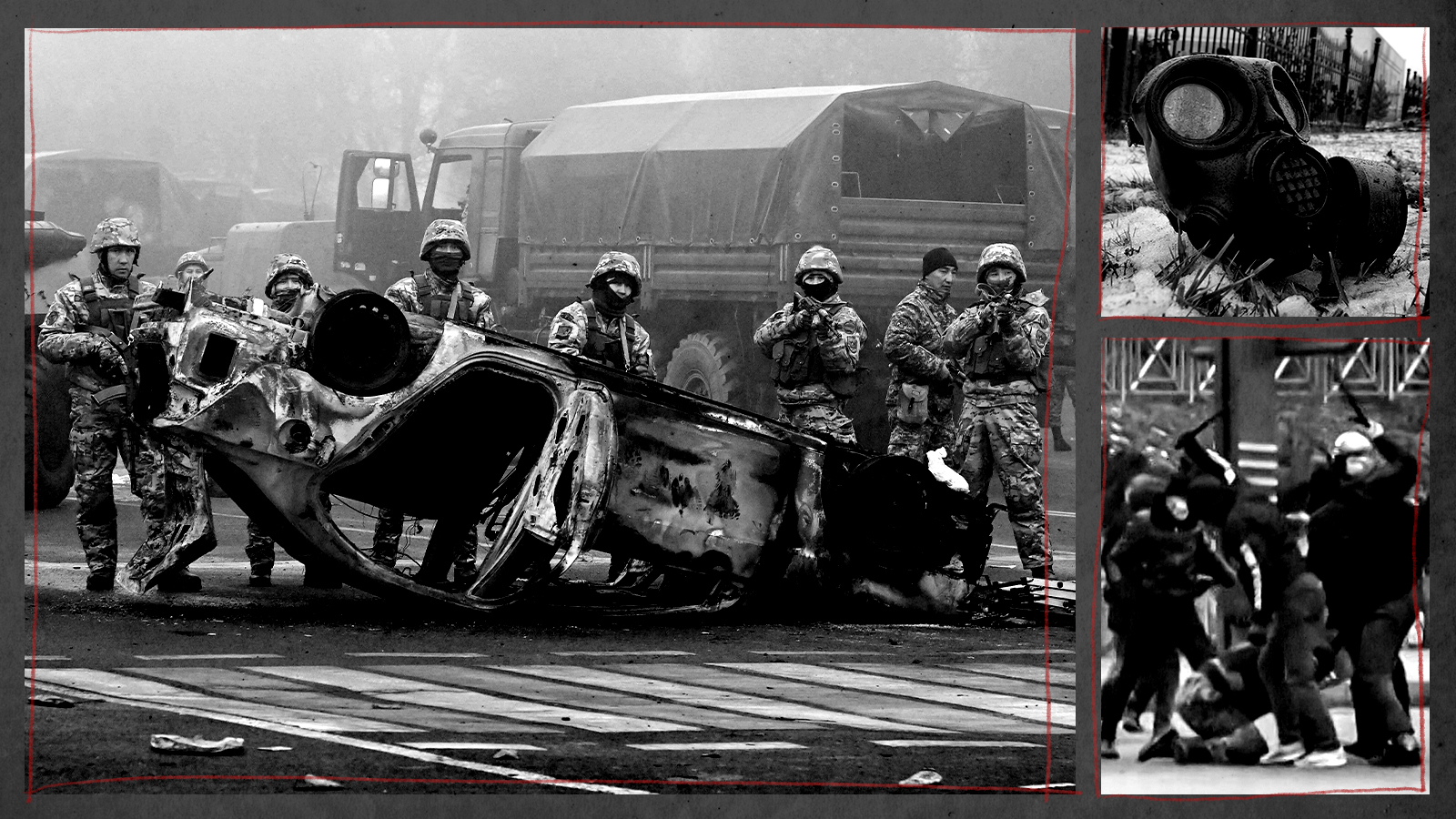

Kazakhstan, Russia, and why recent protests matter

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Kazakhstan was suddenly awash in anti-government protests this week after a revolt over the price of fuel turned into something far more potent and powerful. Here's everything you need to know:

What's going on?

Thousands of Kazakhs across the oil-rich nation have been protesting since Sunday, when the government, in an attempt at moving toward a market economy, lifted a price cap on a commonly-used type of gas. Citizens grew immediately incensed after prices essentially doubled overnight to approximately 100 tenge, or 22 cents, per liter.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The revolt is said to have initially begun with a 10,000-person protest in the oil town of Zhanaozen, the site of an infamous 2011 oil worker strike during which at least 15 were killed by the police. Backlash then continued to spread across the country, even though the government has since reimplemented the price controls.

Things escalated Wednesday, however, when protesters took over the airport in Almaty. Earlier that day, demonstrators stormed and torched the city's main government building; the former presidential residence and the regional branch of the governing Nur Otan party were also set aflame, reports The New York Times. Almaty police say protesters burned "120 cars, including 33 police vehicles, and damaged about 400 businesses," while the Internal Affairs Ministry reported the deaths of eight members of law enforcement (at the time, protesters had not released an equivalent injury or death report). Other demonstrators in Aktau, the capital of the Mangystau region, were also met with gunfire from police.

Meanwhile, the country found itself in a nationwide internet outage as of Tuesday night, conveniently "limiting press coverage, watchdog access and communications within and outside the country," per NPR.

Unrest continued into Thursday, when a Kremlin-led alliance of security forces arrived in Kazakhstan and killed dozens of protesters in Almaty. The alliance, the Collective Security Treaty Organization, includes multiple former Soviet republics like Belarus and Armenia, and serves as "an indication that Kazakhstan's neighbors, particularly Russia, are concerned that the unrest could spread," The Associated Press writes.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

As of Thursday night, the Internal Affairs Ministry had reportedly regained control of all Almaty government buildings. Security forces also recovered the Almaty airport, per the Russian military. On Friday, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev said the government had largely restored order.

Authorities have reported the deaths of dozens of protesters (with many more injured) and 18 security officers.

What are protesters demanding?

The scale and strength of the protests suggests this is no longer about fuel prices at all, especially considering the government already caved on that front.

Dissent is not necessarily a regular occurrence in Kazakhstan, which has more in common with authoritarian regimes than democratic ones. Until 2019, the Central Asian country, which borders Russia to its north and China to its east, was run by President Nursultan Nazarbayev, who — despite handing over control to Tokayev — still wields "tremendous power," per the Times, and serves as the chair of the nation's security council. Nazabayev's reign was "marked by a moderate cult of personality," and included frequent accusations of human rights abuses and autocratic tendencies.

As revolts continued, it became increasingly obvious the uprising had shifted away from the price of automotive fuel in favor of a more powerful, anti-communist political statement — Nazarbayev must go. In Aktau, for example, demonstrators could be heard chanting "shal ket," which is Kazakh for "old man, leave," or "old man, go away."

Central Asia expert Kate Millinson from London's foreign affairs think tank Chatham House told BBC News the protests are "symptomatic of very deep-seated and simmering anger and resentment at the failure of the Kazhak government to modernise their country and introduce reforms that impact people at all levels."

On Friday, protesters issued their most specific list of political demands yet, "asking for a change in power, freedom for civil rights activists, and a return to a 1993 version of the constitution, which is considered to have a more democratic tone and a clearer division of power than the current one," reports The Washington Post.

How has the Khazak government responded?

Though initially soft in its approach, the government has since cracked down on revolts, implementing a strict, nationwide, two-week state of emergency while cautioning demonstrators to steer clear of violence. "Calls to attack civilian and military offices are completely illegal," Tokayev said Tuesday. "This is a crime that comes with a punishment."

The state of emergency includes an 11 p.m.-7 a.m. curfew, movement restrictions, and a ban on large gatherings. Public protests sans-permit were already illegal.

In addition to his decision to once again cap the price of fuel at 50 tenge per liter, Tokayev on Wednesday also removed ex-president Nazarbayev as head of the country's security council; Tokayev's cabinet also resigned, though he said they would remain in their roles until a new one is formed. Despite these efforts, however, the current president has nevertheless failed to calm tensions.

To assist on that front, Tokayev on Thursday called on the aforementioned Kremlin-led military alliance for help quelling unrest he's blamed on "terrorist bands." Stanislav Zas, the CSTO's general secretary, told Russian news that the roughly 2,500 dispatched troops were being sent purely as peacekeepers, not occupiers. Clashes continued throughout Thursday.

On Friday, Tokayev issued a statement alleging the CSTO had "basically restored" constitutional order in most of the country, and said he would "turn the internet back on," though with accessibility limits and government monitoring. On a more sinister note, Tokayev also gave police and military the order to shoot protesters without warning.

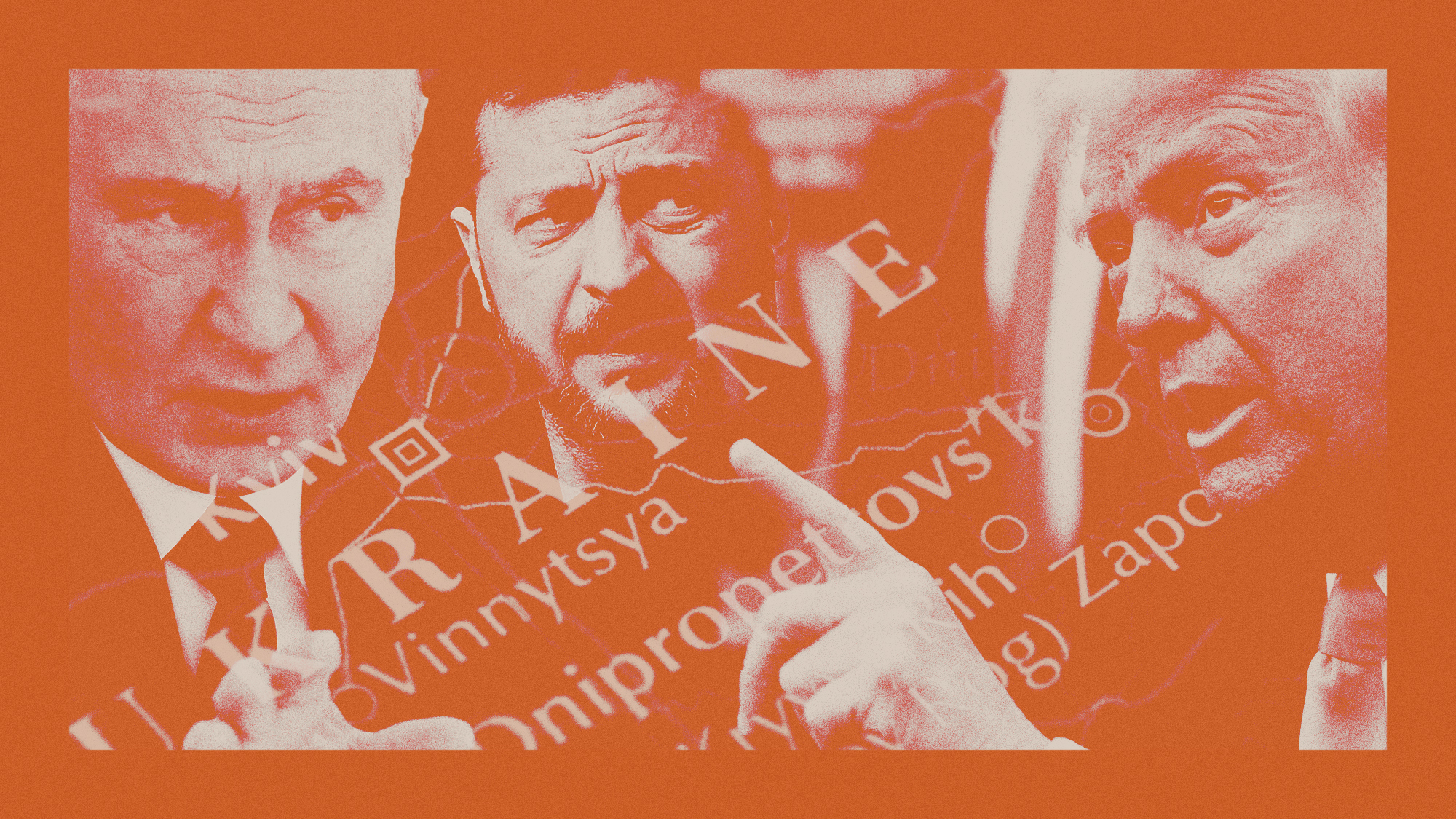

How does Russia factor into all of this?

In quite a few ways.

For one thing, writes the Times, Russian President Vladimir Putin is now being "forced to witness" yet another "uprising against an authoritarian, Kremlin-aligned nation," likely much to his dismay, considering Putin still views the country as falling under his sphere of influence.

The revolts also represent a sort of "warning" for Moscow, given the Khazak government is almost a "reduced replica of the Russian one." "If something like this can happen in Kazakhstan," Scott Horton, who has advised Kazakh and other Central Asian officials over two decades, told the Times, "it can certainly happen in Russia, too."

Furthermore, though Russia deployed the CSTO security alliance (its response to NATO) for Tokayev, "such assistance is seldom offered free of charge," the Times notes. Of course, Moscow doesn't like seeing a former republic in such distress, but at least now the Khazakh president owes them "big time," noted Melinda Haring of the Atlantic Council's Eurasia Center.

What about the U.S.?

The U.S. government is closely monitoring CSTO forces for violations of human rights or attempts to seize control of Kazakh institutions, State Department spokesperson Ned Price said Thursday.

Despite its former Soviet ties, oil-rich Kazakhstan has become a trusted partner of the United States — particularly as it relates to American energy concerns, notes the Times; just last September, President Biden told President Tokayev that "the United States is proud to call your country a friend." Now, however, the entry of the CSTO may "upset the equilibrium Kazakhstan has managed to find between the East and West," notes Foreign Policy.

Said University of Pittsburgh Central Asia expert Jennifer Brick Murtazashvili: "I think it's a huge blow to Kazakhstan's sovereignty, and it really alters the balance of power in the region."

Brigid Kennedy worked at The Week from 2021 to 2023 as a staff writer, junior editor and then story editor, with an interest in U.S. politics, the economy and the music industry.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

Alexei Navalny and Russia’s history of poisonings

Alexei Navalny and Russia’s history of poisoningsThe Explainer ‘Precise’ and ‘deniable’, the Kremlin’s use of poison to silence critics has become a ’geopolitical signature flourish’

-

US, Russia restart military dialogue as treaty ends

US, Russia restart military dialogue as treaty endsSpeed Read New START was the last remaining nuclear arms treaty between the countries

-

What happens now that the US-Russia nuclear treaty is expiring?

What happens now that the US-Russia nuclear treaty is expiring?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION Weapons experts worry that the end of the New START treaty marks the beginning of a 21st-century atomic arms race

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Ukraine, US and Russia: do rare trilateral talks mean peace is possible?

Ukraine, US and Russia: do rare trilateral talks mean peace is possible?Rush to meet signals potential agreement but scepticism of Russian motives remain