What is China’s Belt and Road initiative?

UK agrees to help huge project amid growing concern over debt-trap diplomacy

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Chancellor Philip Hammond has said the UK is committed to helping realise the potential of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Hammond was speaking at a Beijing summit on China’s ambitious project to recreate the ancient Silk Road joining China with Asia and Europe. The BRI must work for everyone if it is to become a sustainable reality, he said, before offering British expertise in project financing.

But in what the Financial Times describes as “a sign of the sensitivities around the project”, the British embassy in Beijing barred media from attending the chancellor’s speech.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

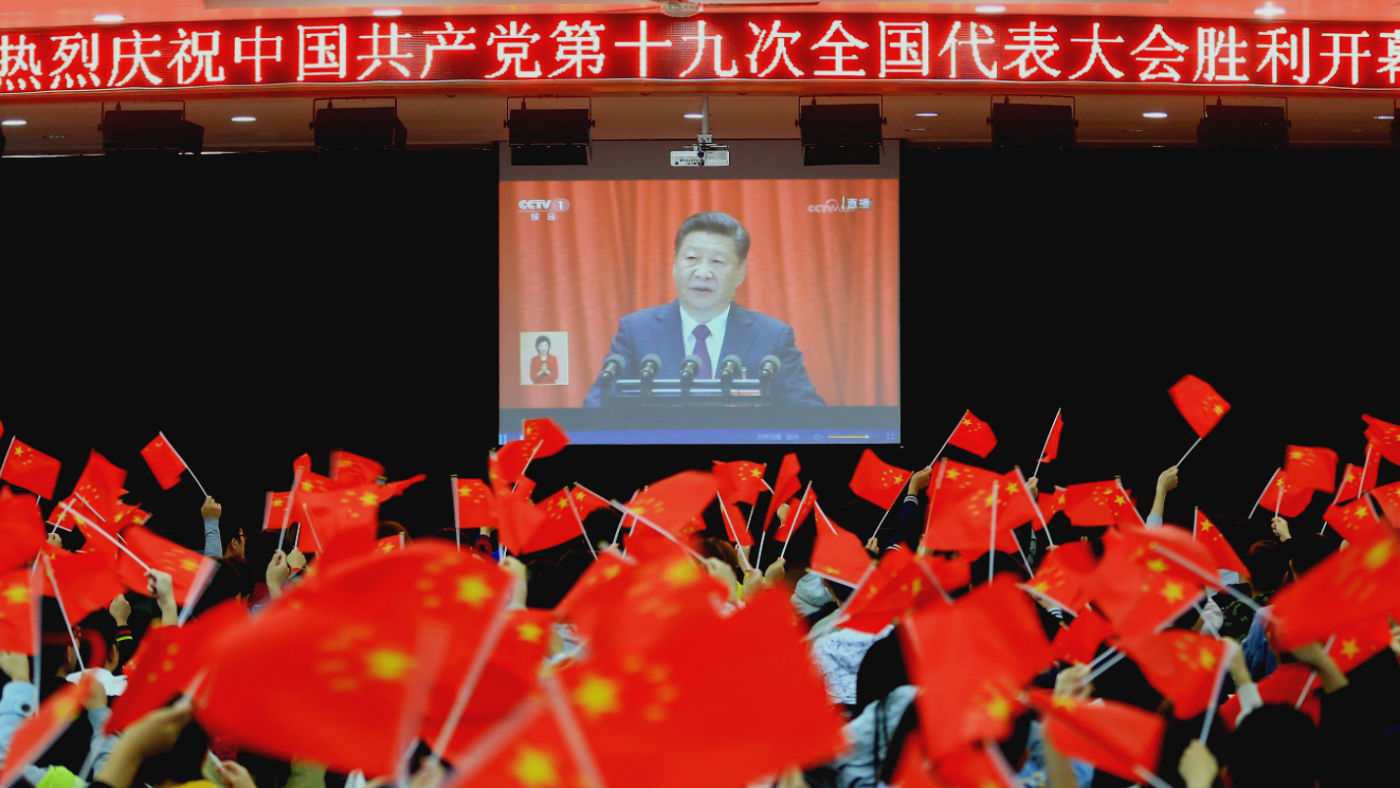

“As Western divisions over China were laid bare at a forum on his flagship foreign policy”, China’s President Xi Jinping pledged a more open approach to the BRI, says the newspaper.

Xi told the forum that he would open domestic markets, make financing of the country’s overseas investments more transparent and ease import and customs barriers.

“Today’s China is already at a new historic point,” he said. “Despite the glory of our achievements, there are still mountains that must be scaled.”

Seven EU countries are set to back the initiative, according to a draft of the final communique, “despite the reservations of some of the EU’s biggest member states over the infrastructure building programme”, the newspaper adds.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But what exactly is the BRI and why is it controversial?

What is it?

The ambitious project has already funded trains, roads and ports in an attempt to echo the geographic footprint and spirit of the ancient land and maritime Silk Roads that once linked Asia, Africa and Europe. However, the BRI also looks much further afield, expanding to countries from Burkina Faso to El Salvador.

President Xi said the aim of the infrastructure programme was “to enhance connectivity and practical cooperation”.

Total trade between China and other Belt and Road countries has already exceeded $6trn (£4.65trn), and the programme is expected to involve over $1trn (£0.77trn) in investments from China.

But there is another motive to the project too, say experts. “The overall purpose of the Belt and Road initiative is to generate legitimacy for the Chinese leadership and the Chinese Communist Party more broadly,” Thomas Eder, a research associate at the Mercator Institute for Chinese Studies, told The Guardian.

“Such prestige is bolstered by every government signing a BRI memorandum of understanding and every head of government attending a grand BRI summit in Beijing. These countries allow Xi Jinping to then tell Chinese citizens that the entire world is endorsing his policies and that he is the one to have put China firmly back at the centre of the global stage,” Eder said.

Who’s involved?

So far 126 countries and 29 international organisations have signed BRI cooperation documents with China. Italy became the first G7 country to endorse the initiative, after signing up in March, despite criticism from the US.

The US has so far refused to take any part in the initiative, with officials saying it is an attempt to undermine US influence across the globe.

Why is it controversial?

Critics say the initiative is an effort to cement Chinese influence around the world by financially binding countries to Beijing by way of “debt-trap diplomacy”.

This is a charge China denies. “The BRI is not a geopolitical tool but a platform for cooperation,” Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi said last week.

But China has also “played on European fears of immigration as part of its outreach”, says the FT. An April report by the Belt and Road Forum advisory council, a group of retired international officials co-ordinated by the Chinese foreign ministry, argued that infrastructure investment in Africa would provide jobs and development.

“On this score the Belt and Road co-operation could be deemed as ‘A Gift to Europe’,” the report said.

Some partner nations have bemoaned the high cost of the BRI projects. “Those that have been shelved for financial reasons include a power plant in Pakistan and an airport in Sierra Leone,” says Reuters.

In Pakistan, militants in Balochistan have attacked BRI projects and workers, accusing China of exploiting the resource-rich, cash-poor province.

Other critics have also cited environmental concerns, as Chinese companies build coal power projects around the world. Coal projects accounted for as much as 42% of China’s overseas investment in 2018, according to the China Global Energy Finance database.

Perhaps the biggest issue with it “is its sheer ambition”, says The Economist. A recent study by the World Bank concluded that BRI transportation projects could lift global GDP by 3%. But “the scale of the effort is a huge challenge, and such projects are a magnet for graft”, says the magazine. Vast sums “are being spent quickly in badly run places”, it adds.

Experts believe China cannot realise the BRI dream alone, but its often hubristic approach of asking others “not only to sign up to its infrastructure plans but also to endorse Xi’s world view” has alienated potential partners.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire

-

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by Russia

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by RussiaSpeed Read The ship was one of two vessels seized by the US military