Alan Turing: from persecuted pioneer to face of the £50 note

Codebreaker who helped defeat the Nazis is to be honoured by the Bank of England

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

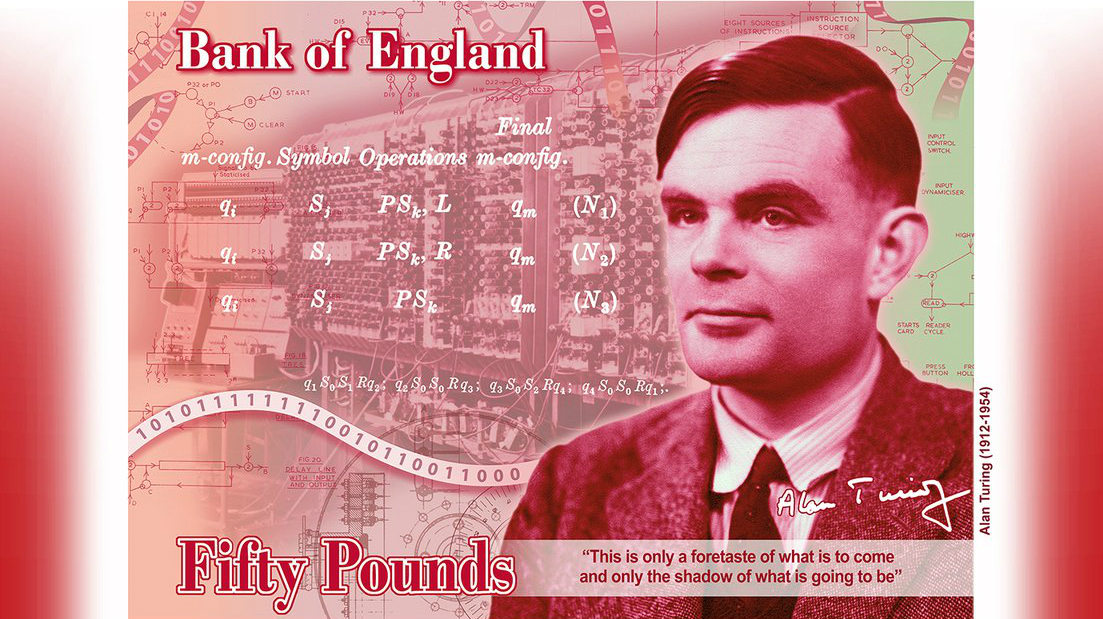

Celebrated Second World War codebreaker Alan Turing will be commemorated on the new £50 note after being chosen from more than 1,000 contenders for the honour.

Announcing the decision during a speech at the Science and Industry Museum in Manchester, Bank of England governor Mark Carney said that the so-called father of computing will appear on the new polymer note by the end of 2021.

Carney also revealed imagery depicting Turing and his work that will be used for the reverse of the note, Sky News says.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

“Alan Turing was an outstanding mathematician whose work has had an enormous impact on how we live today,” Carney said.

“As the father of computer science and artificial intelligence, as well as [a] war hero, Alan Turing’s contributions were far-ranging and path-breaking. Turing is a giant on whose shoulders so many now stand.”

Turing’s pivotal role in helping the Allied forces defeat Nazi Germany during WWII has seen him venerated by the British public, with the scientist named the greatest person of the 20th century in a BBC poll earlier this year.

But Turing’s achievements were acknowledged with rather less fanfare during his life. In the 1950s, he was prosecuted and convicted on charges of homosexuality, which at the time was a criminal offence in the UK. Just two years after his arrest, he committed suicide at the age of 41.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Posthumously, Turing has been the recipient of numerous awards and honours, and even received an official apology from the UK Government in 2009. Here’s a look at the life of the genius set to be honoured on the £50 note.

WWII hero

Turing was born in London in 1912 and was an excellent student at school before attending King’s College, Cambridge in 1931, where he received a first in mathematics.

The Guardian reports that during his masters degree at the university, Turing came up with “a number of seminal ideas” including “his vision of a universal computing machine, which can be fed an algorithm for a particular computation and then apply it”. Turing’s later revisions of this idea are described by the Imperial War Museum as “arguably the forerunner to the modern computer”.

After a period working in codebreaking and studying for a PhD at Princeton University in the US he joined Bletchley Park, the Buckinghamshire codebreaking station, at the outbreak of the Second World War.

His initial goal was to break Enigma codes used by the Axis powers in order to distrupt Germany’s extraordinary naval prowess in the early years of the war. Forbes reports that during the first three months of 1942, German U-boats “sank more than 100 ships off the east coast of North America, in the Gulf of Mexico and in the Caribbean Sea”.

Turing was put in charge of Hut 8 at Bletchley Park and, working with Joan Clarke and Polish counterparts, he designed the Bombe: a “purpose built British cryptanalytic machine that helped to break the Enigma used by the Axis”, Gloucestershire Live says.

Turing and his team decoded naval and U-boat messages that had previously been regarded as unbreakable, revealing information about German positions that “helped to shift advantage to the allies during the battle for the Atlantic”, according to The Independent.

The BBC suggests that at a conservative estimate, “each year of the fighting in Europe brought on average about seven million deaths”, and that, had Enigma not been broken, the war might have “continued for another two to three years”.

As such, the broadcaster estimates that between 14 million and 21 million more people might have been killed had Turing not cracked the codes.

Postwar and arrest

For his role in deciphering German intelligence, Turing was awarded an OBE in 1946, but much of his work went unrecognised by the public because of government secrecy laws.

He went on to work at Victoria University in Manchester, where he helped create an innovative series of stored-program electronic devices now dubbed the “Manchester computers”.

His groundbreaking 1950 paper Computing Machinery and Intelligence is considered the “first cogent attempt at describing in detail how computers could one day ‘think’”, Forbes says.

But Turing’s life took an ultimately tragic turn. In January 1952, while having a homosexual relationship with a 19-year-old man called Arnold Murray, Turing’s house was robbed while he was meeting Murray in central Manchester. Murray revealed that he had connections to the burglar, prompting Turing to go to the police.

He was forced to disclose his relationship with Murray to the police at a time when homosexual acts were illegal. Gloucestershire Live adds that, despite the head of cryptanalysis at GCHQ, Hugh Alexander, speaking as a character witness on Turing's behalf and describing him as a “national asset” during the trial, Turing was found guilty of gross indecency and “had to decide between going to prison or undergoing chemical castration”.

He chose the latter, with the subsequent hormone treatment leaving him impotent. He was also barred from accessing or working with GCHQ and was denied entry into the US.

Death

Two years after choosing castration Turing took his own life at the age of 41 by eating an apple laced with cyanide.

CNN reports that sex between men over the age of 21 was decriminalised in England and Wales in 1967.

After thousands of people signed a petition in the late 2000s, the then prime minister Gordon Brown issued an official apology in 2009 for Turing's treatment by the justice system in the 1950s, and he received a royal pardon from the Queen in 2013.

On announcing the decision to put him on the £50 note, the Bank of England said of Turing: “He set the foundations for work on artificial intelligence by considering the question of whether machines could think.

“Turing was homosexual and was posthumously pardoned by the Queen, having been convicted of gross indecency for his relationship with a man. His legacy continues to have an impact on both science and society today.”

John Leech, the former Lib Dem MP for Manchester Withington who campaigned for Turing to be pardoned, described the move as a “rightfully painful reminder of what we lost”, but added that he was “absolutely delighted” that Turing will be the face of the new £50 note.

“It is almost impossible to put into words the difference that Alan Turing made to society, but perhaps the most poignant example is that his work is estimated to have shortened the war by four years and saved up to 21 million lives,” the former MP said. “And yet the way he was treated afterwards remains a national embarrassment and an example of society at its absolute worst.”