Five ways Formula E will change electric cars

The cars competing in the ABB Formula E championship may look like F1 racers, but their technology may find its ways into your next car

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Formula E is a sport with a purpose, and one which goes beyond the usual competitive aim of establishing who goes furthest, fastest, strongest.

The championship, in which 25 battery-powered cars zip around 12 city-centre race courses, is “a platform to promote electric vehicles”, says Renato Bisignani, the tournament’s director of communications. Innovation is “a core value”.

Racing technology has, of course, always trickled down to road cars. Disc brakes, ABS and active suspension are among the technologies pioneered in the pit lane, but their broader application was often an afterthought. In Formula E, by contrast, transferable technology is a primary goal.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

“It’s still motorsport, it’s still what we love, but it’s actually opening the doors to other places,” says Allan McNish, a former F1 driver and now team principal for Audi’s Formula E team. “We’re all about pushing electric technology.”

That sense of purpose is embedded in the rules of the race, which bar teams from spending their budgets on features that won’t benefit road cars - for example, on tweaking the aerodynamics of the body. Instead, engineers have to work on new ways of getting more power and range out of the battery.

“The people that will win the race are the ones that will maximise energy efficiency, which is what we need to do as a society,” says Tarak Mehta, president of electrification at ABB, Formula E’s title sponsor and a big player in the electrical infrastructure business.

Here are five ways in which Formula E is likely to benefit the road cars of the future:

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Longer range

The biggest obstacle to wider adoption of electric cars is so-called range anxiety - the fear of being stranded when the power runs out. While battery technology is improving fast, the rules of Formula E require all teams to use the same power plant - a 54 kWh unit made by McLaren.

That’s because this kind of high-performance battery is expensive, says Bisignani, and won’t find its way into production cars any time soon. Money spent tweaking it would therefore not benefit the industry at large, and would divert resources away from energy management and recovery through regenerative braking. These, he says, “are directly relevant to the automotive industry”.

Michael Carcamo, Nissan’s global motorsport director, agrees. “The area that’s most interesting is how you consume energy,” he says. “If you focus on control systems, those control systems are the same building blocks, the same strategies you have to use on production cars.”

Speaking before his team won the penultimate race of the season in New York, Carcamo says Nissan’s involvement in Formula E has helped the company build better road cars. “We were able to take specific areas of software and apply them to our cars,” he says.

Reliability

Electric cars are mechanically simpler than those powered by petrol and diesel, with far fewer moving parts, but the new components they require have not been tested by decades of real-world trials. Putting them on a racecourse accelerates the endurance-testing programme and finds out what happens when they are pushed beyond their limits.

That’s particularly true with Formula E’s city-centre circuits, made up of imperfectly surfaced public streets. “We are just driving on the roads that you are taking with your car,” says Edoardo Mortara, who drives for the Venturi racing team. That makes them a truer test than the ultra-smooth surfaces of F1, he says: “I hardly know any normal roads where there are no bumps.”

Jaguar says its electric cars will be tougher as a result of Formula E and, more directly, the I-Pace E-Trophy, in which Jaguar I-Pace electric SUVs race against each other around the Formula E tracks.

“The road cars will never be driven as hard as these, so we’ve learnt a lot that we’re now putting back into the road cars,” says Adam Jones, Jaguar Land Rover’s technical manager. Some components initially weren’t strong enough for racing conditions, he says, but “road engineers back in the UK are now working with what they’ve learnt on the racing track”.

Fast charging

As batteries get more powerful and engineers get better at using that power effectively, range anxiety will decrease. “In the next two to three years you will not need to worry if you want to go 300 miles,” says ABB’s Mehta. “The technology will get you there.”

The focus will then switch away from range and towards the experience of recharging - another barrier to adoption. While few people look forward to a trip to the petrol station, at least refuelling doesn’t take more than a couple of minutes. Refilling with electricity can be a slower process.

Overnight trickle-charging from household mains sockets is part of the answer, but motorists will also demand fast and ubiquitous charging stations to top them up mid-journey. The Jaguar I-Pace batteries are powered with a compact version of ABB’s fast-charging system, developed specifically for the event, which replenishes the high-capacity batteries between qualifying and racing. For a standard electric road car, the ABB fast-charger can add about 125 miles of range in eight minutes.

ABB has sold about 1,200 of these so far, a baby step towards a completely new energy infrastructure. “We need to put in so many thousands of charging points,” says Mehta. “It’s not a small problem.”

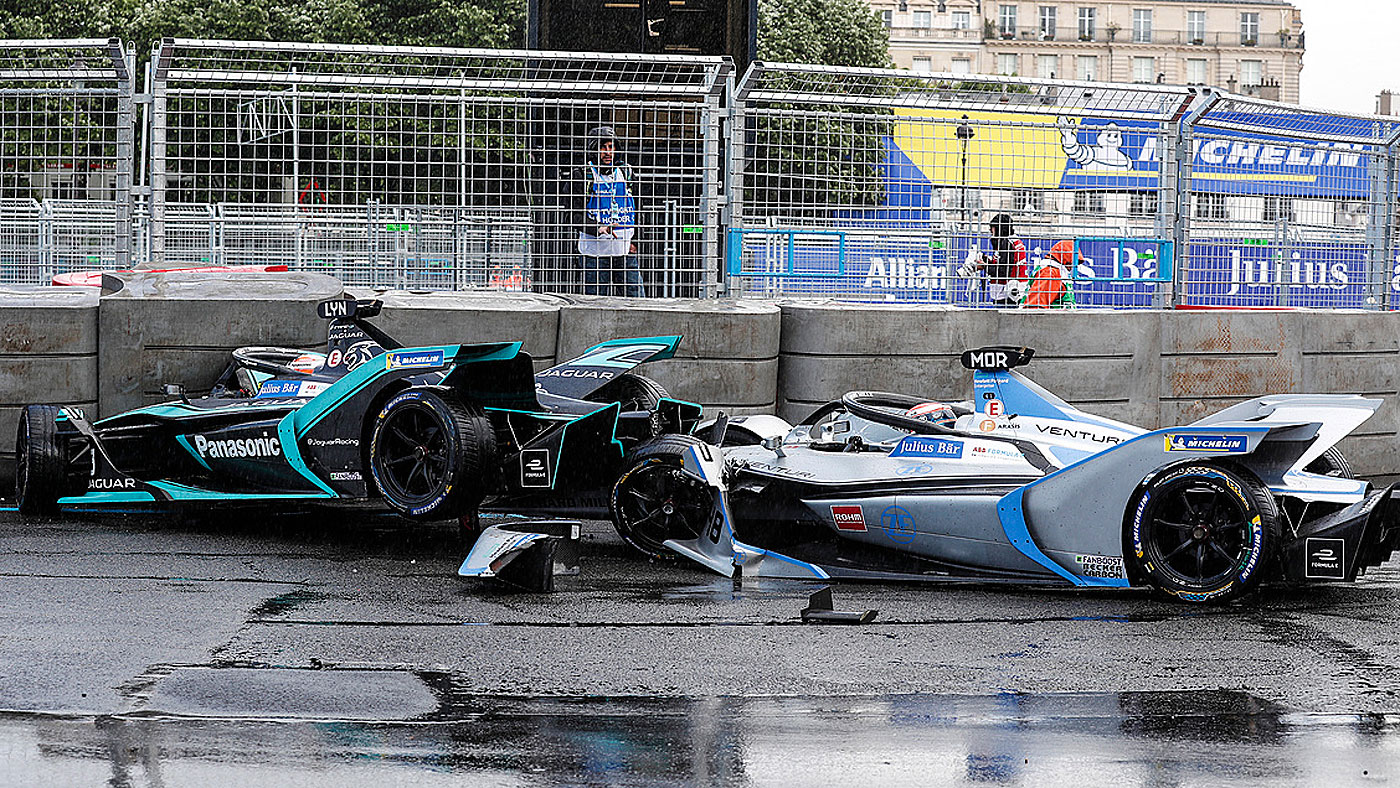

Safety

While internal combustion engines are not without risk - petrol is, after all, highly flammable - engineers have spent a century minimising those dangers and consumers have come to accept them. Electrocution, by contrast, is a hazard that drivers have not had to reckon with.

In normal circumstances, the danger is all but non-existent, but a serious accident could damage the electrical system to the extent that live current ends up passing through the chassis. That would pose a risk to both the occupants of the car and emergency workers coming to the rescue.

Given the speeds involved - and the regular accidents - motor racing is the ideal testing ground for safety features, many of which make their way into road cars.

Both the Formula E and Jaguar I-Pace cars use a traffic-light system to display the status of the electrical system to drivers and paramedics: green means all is well, blue indicates an impact of 16G and red that the battery or circuitry has been compromised. In that case, emergency cut-off switches inside and outside the car can be used to isolate the battery.

The regular beatings taken by Formula E cars - the electric series is far more physical than F1 - also helps to demonstrate the safety of electric propulsion, even in extreme conditions.

Image

Early electric cars, such as the Reva G-Wiz, were not great ambassadors for battery power. Flimsy, slow and poorly built, they could hardly be further from today’s electric cars. And that may matter as much as practical concerns about cost and range, since buying a car is an emotional decision as well as a rational one.

Formula E adds glamour and excitement, alongside the environmental credentials. “The kind of performance you see will match many of the statistics you see in Formula 1,” says Mehta. Those figures may be out of reach of electric Minis and Golfs, but even they have an advantage over their fossil-fuel-burning forebears. “Compare two cars of the same horsepower,” he says, “one electric one petrol. The electric one will be faster.”

That’s because of the way electric motors deliver their power and torque: smoothly and consistently at all speeds (unlike petrol and especially diesel engines, which have sweet spots and dead spots as they accelerate through their gears).

High-performance electric cars from Tesla, BMW and Jaguar have helped overthrow the milk-float image, but racing has played its part too. When Jeremy Clarkson, an early tormentor of the G-Wiz, said this month he would rather watch Formula E than Formula 1, it marked a coming of age for electric power.

Holden Frith is The Week’s digital director. He also makes regular appearances on “The Week Unwrapped”, speaking about subjects as diverse as vaccine development and bionic bomb-sniffing locusts. He joined The Week in 2013, spending five years editing the magazine’s website. Before that, he was deputy digital editor at The Sunday Times. He has also been TheTimes.co.uk’s technology editor and the launch editor of Wired magazine’s UK website. Holden has worked in journalism for nearly two decades, having started his professional career while completing an English literature degree at Cambridge University. He followed that with a master’s degree in journalism from Northwestern University in Chicago. A keen photographer, he also writes travel features whenever he gets the chance.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

BMW iX3: a ‘revolution’ for the German car brand

BMW iX3: a ‘revolution’ for the German car brandThe Week Recommends The electric SUV promises a ‘great balance between ride comfort and driving fun’

-

The best new cars for 2026

The best new cars for 2026The Week Recommends From SUVs to swish electrics, see what this year has to offer on the roads

-

Are plug-in hybrids better for America's climate goals?

Are plug-in hybrids better for America's climate goals?Talking Points The car industry considers a 'slower, but more plausible path' to reducing emissions

-

EV market slowdown: a bump in the road for Tesla?

EV market slowdown: a bump in the road for Tesla?Talking Points The electric vehicle market has stalled – with worrying consequences for carmakers

-

The week's good news: Dec. 14, 2023

The week's good news: Dec. 14, 2023Feature It wasn't all bad!

-

MG4 EV XPower review: what the car critics say

MG4 EV XPower review: what the car critics sayFeature The XPower just 'isn't as much fun' as a regular MG4

-

Volkswagen ID.5 review: what the car critics say

Volkswagen ID.5 review: what the car critics sayFeature The ID.4's 'sportier, more stylish twin' – but 'don't believe the hype'

-

BMW iX1 review: what the car critics say

BMW iX1 review: what the car critics sayThe Week Recommends BMW’s smallest electric crossover has ‘precise’ steering and a ‘smart interior’