What is the fish hook theory?

Political concept takes aim at those in the political centre

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

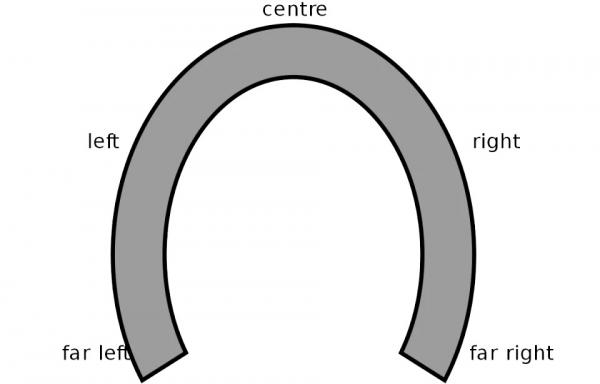

The so-called horseshoe theory that the far-left and far-right more closely resemble each another than they do the political centre has been around for decades, but now an alternative is gaining ground: fish hook theory.

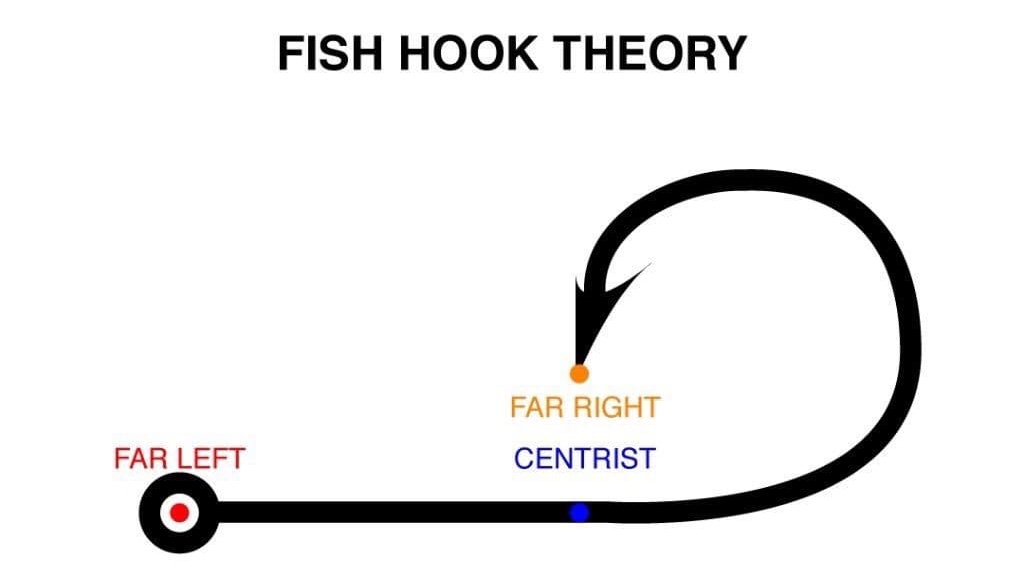

Instead of a straight line, or a horseshoe where the two ends almost touch, the fish hook theory sees the political Left out on one end, and the Right bending around like a hook to end up close to the centre.

The suggestion is that people who are politically centrist are actually a lot closer to far-right politics than their “centre” label suggests.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How did fish hook theory originate?

Fish hook theory was developed in response to horseshoe theory.

Leftists unhappy with the suggestion that they are aligned to the far-right came up with the fish hook theory partly to satirise the horseshoe theory, but also because they believe the centre often does makes way for the Right.

Or as California-based online magazine Pacific Standard puts it: “Centrists enable fascism with such predictable frequency that the Left has come up with an alternative to horseshoe theory: fish hook theory.”

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Leftists pushing fish hook theory argue that there is a strong intersection between centrist neoliberalism and fascism, and that the freedoms of the former can lead to the rise of the latter.

“Freedom from trade unions and collective bargaining means the freedom to suppress wages,” writes George Monbiot in The Guardian.

“Freedom from regulation means the freedom to poison rivers, endanger workers, charge iniquitous rates of interest and design exotic financial instruments. Freedom from tax means freedom from the distribution of wealth that lifts people out of poverty.’”

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––For more political analysis - and a concise, refreshing and balanced take on the week’s news agenda - try The Week magazine. Get your first six issues free–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Is there truth to it?

The theory holds that because of the apparent proximity between far-right and the political centre, centrists are susceptible to adopting fascist beliefs and can pave the way for fascist rule.

“Centrists are the least supportive of democracy, the least committed to its institutions and the most supportive of authoritarianism,” says David Adler in The New York Times. “As Western democracies descend into dysfunction, no group is immune to the allure of authoritarianism - least of all centrists, who seem to prefer strong and efficient government over messy democratic politics.”

However, many commentators argue that far-right politics has elements that could appeal to people on the far-left as much as the centre. They point out that populism, ideological purity and a feeling of embattlement are common to the the far-right and far-left, but less prevalent in the centre.

“Call it tendril theory,” concludes The Week US. “Fascism extends its slimy feelers out to centrists and leftists alike.”

However, the theory relies on the assumption that “left-wing” and “right-wing” are helpful and widely-recognised terms when we talk about people’s views – and research by YouGov suggests otherwise.

The pollsters found that, at most, only half of those surveyed understood what a left-wing policy and a right-wing policy was. “That is to say”, explains data journalist Matthew Smith, “even for the very most stereotypically left- and right-wing policies, half of the population do not identify them as such”.

The opinion pollsters also found that nearly 50% of Britons regard themselves as neither left-wing nor right-wing. Although 28% describe themselves as left-wing and 25% consider themselves right-wing, a further 19% place themselves in the centre and the remaining 29% don’t know.

Given that around half of the British public do not regard themselves as “left-wing” or “right-wing” - and that a similar proportion struggle to position policies on that spectrum - the usefulness of the fish-hook theory is open to debate.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

How corrupt is the UK?

How corrupt is the UK?The Explainer Decline in standards ‘risks becoming a defining feature of our political culture’ as Britain falls to lowest ever score on global index

-

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?In the Spotlight Mass closure of shops and influx of organised crime are fuelling voter anger, and offer an opening for Reform UK

-

Is a Reform-Tory pact becoming more likely?

Is a Reform-Tory pact becoming more likely?Today’s Big Question Nigel Farage’s party is ahead in the polls but still falls well short of a Commons majority, while Conservatives are still losing MPs to Reform

-

Revisionism and division: Franco’s legacy five decades on

Revisionism and division: Franco’s legacy five decades onIn The Spotlight Events to mark 50 years since Franco’s death designed to break young people’s growing fascination with the Spanish dictator

-

Taking the low road: why the SNP is still standing strong

Taking the low road: why the SNP is still standing strongTalking Point Party is on track for a fifth consecutive victory in May’s Holyrood election, despite controversies and plummeting support

-

America: Are we now living in an autocracy?

America: Are we now living in an autocracy?Feature 200 days into his presidency and Trump is still deepening his authoritarian grip

-

What difference will the 'historic' UK-Germany treaty make?

What difference will the 'historic' UK-Germany treaty make?Today's Big Question Europe's two biggest economies sign first treaty since WWII, underscoring 'triangle alliance' with France amid growing Russian threat and US distance

-

Is the G7 still relevant?

Is the G7 still relevant?Talking Point Donald Trump's early departure cast a shadow over this week's meeting of the world's major democracies