Coronavirus: will the pandemic change our economic system?

Long-term effects expected to include more government debt and fewer calls for privatisation

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

22 February 2021: ‘The pandemic will change society forever’

Rishi Sunak is preparing to phase out the coronavirus wage-subsidy scheme for furloughed workers as part of the government’s plans to end the UK lockdown.

The chancellor is expected to announce that the coronavirus Job Retention Scheme will be scaled back from July, as restrictions on business are lifted.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The pandemic has put unprecedented strain on both the British and world economy - prompting questions about how the crisis may change economic systems in the long term.

What are Sunak’s plans?

The chancellor is reportedly considering lowering the 80% wage subsidy paid by the state to 60%, and cutting the £2,500 cap on monthly payments.

Another option would be to allow furloughed staff to work reduced hours, with a smaller state subsidy.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Sources have “indicated that a final decision has yet to be made, but the Treasury was working closely with No. 10 as Boris Johnson prepares to outline plans on Sunday to gradually lift lockdown restrictions”, says The Guardian.

How is the UK economy faring now?

HMRC figures released this week show that 6.3 million staff from a total of 800,000 companies had been furloughed as of the end of last week, reports City A.M..

That represents more than a fifth of the UK workforce, with the government paying £8bn in staff wages during the first month of the scheme.

And the Office for Budget Responsibility has estimated that the total cost could reach £42bn over three months, based on 8.3 million people being furloughed at 80% subsidy.

The scheme would cost a further £12bn for each additional month at this level, according to the Resolution Foundation think tank.

Meanwhile, the threat of mass unemployment looms, amid fears that many companies will be unable to afford to rehire furloughed workers.

What will happen in the longer term?

The UK is on track for its deepest economic downturn in many decades, according to a recent survey by IHS Markit/CIPS that showed the UK’s dominant services sector contracted at a record pace in April.

IHS Markit economics director Tim Moore told the BBC that the data “highlights that the downturn in the UK economy during the second quarter of 2020 will be far deeper and more widespread than anything seen in living memory”.

Government debt had surged even before the coronavirus pandemic, after a series of Conservative leaderships moving away from the economic system of borrowing. “The budget deficit is forecast to exceed £200bn this year, with debt surpassing 100% of GDP,” reports the New Statesman.

Calls are already emerging for the implementation of austerity measures when the Covid-19 crisis has eased, despite Boris Johnson insisting that this economic policy will “certainly not be part of our approach”.

A key to longer term recovery will be for businesses to retain workers.

Typically in economic downturns, companies shed staff, who then spend less elsewhere, which in turn results in other redundancies, spiralling into economic depression.

“In a normal crisis, the prescription for solving this is simple. The government spends, and it spends until people start consuming and working again,” says Simon Mair, a research fellow at the University of Surrey’s Centre for the Understanding of Sustainable Prosperity, in an article on The Conversation.

“But normal interventions won’t work here because we don’t want the economy to recover (at least, not immediately). The whole point of the lockdown is to stop people going to work, where they spread the disease.”

Or to put it another way, lifting lockdown measures completely and sending everybody off to spend freely in shops, pubs and restaurants will only risk a second peak of coronavirus infections. Instead, the government has to give people enough freedom to stimulate the economy without being forced into declaring a second lockdown.

Public health has always been a keenly watched element of government policy, but the spotlight has grown increasingly bright as a result of the pandemic. In the UK, the state has taken unprecedented decisions in the interest of public health and protecting the health service.

Such government intervention is likely to continue, reversing trends over past decades that have seen public systems “come under increasing pressures to marketise, to be run as though they were businesses who have to make money”, writes Mair.

Mariana Mazzucato, an economics professor at University College London, told the New Statesman: “It is not enough to clap NHS workers and throw money at the service in times of emergency, the structure of our health system, and the public organisations around it, need to be strengthened, properly remunerated and nurtured.”

The UK economy still relies heavily on trade with Europe, and was already facing the economic disruption of Brexit before anybody had heard of Covid-19. But now, as well as having Brexit to contend with - and the government insists that it will be contended with - the UK faces the added problem of the weakened economic states of key trading partners in Europe.

Writing in The Guardian, Greece’s former finance minister Yanis Varoufakis warns that the “endpoint” of this weakening of the Continent’s various countries could be “a giant domino effect, leading to the disintegration of the European Union. Not that the EU will cease to exist. Only that it will become irrelevant.”

-

Political cartoons for February 21

Political cartoons for February 21Cartoons Saturday’s political cartoons include consequences, secrets, and more

-

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?Talking Point The Trump administration is applying the pressure, and with Latin America swinging to the right, Havana is becoming more ‘politically isolated’

-

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predators

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predatorsCartoons Artists take on the real victim, types of protection, and more

-

How corrupt is the UK?

How corrupt is the UK?The Explainer Decline in standards ‘risks becoming a defining feature of our political culture’ as Britain falls to lowest ever score on global index

-

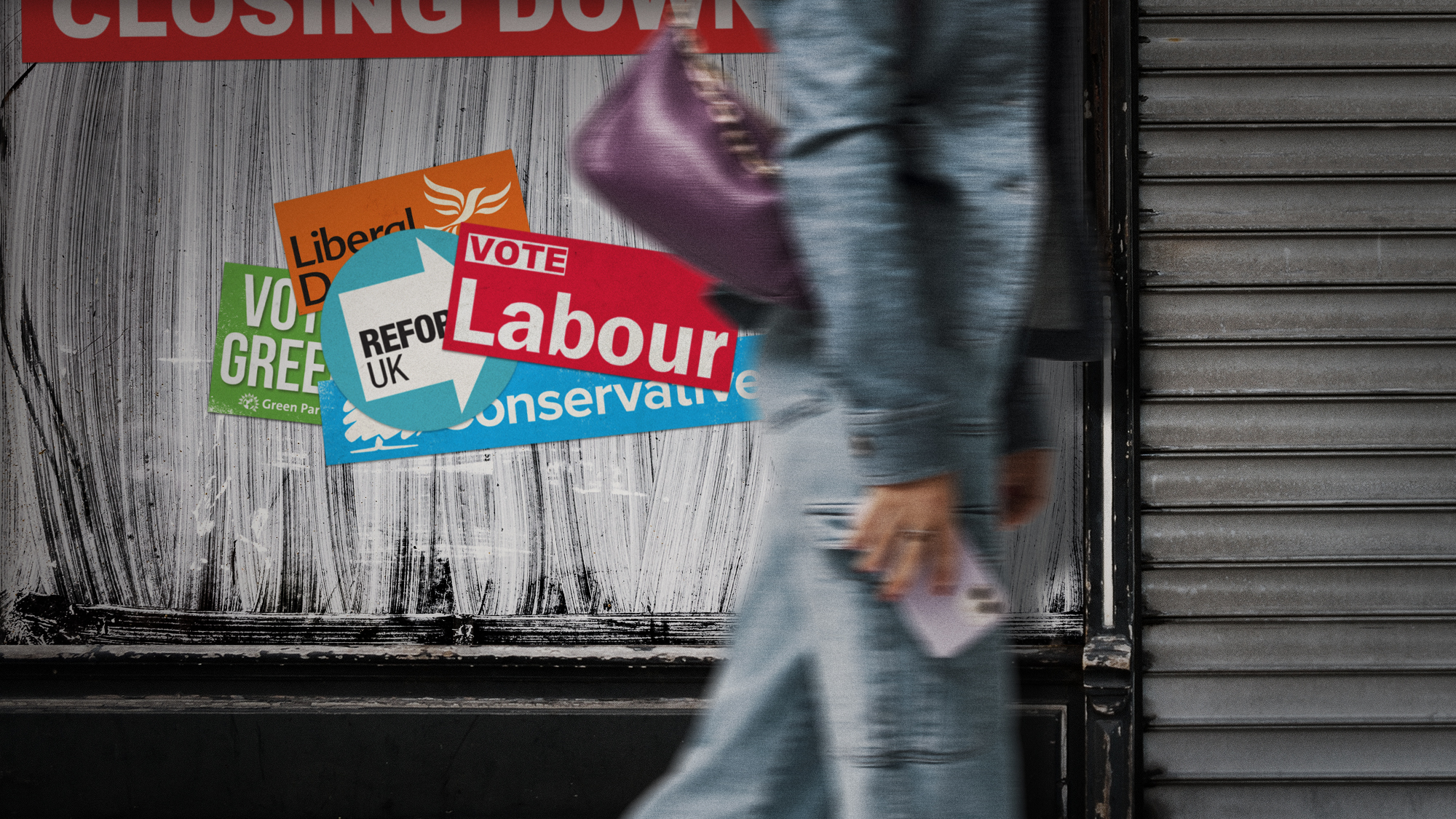

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?In the Spotlight Mass closure of shops and influx of organised crime are fuelling voter anger, and offer an opening for Reform UK

-

Is a Reform-Tory pact becoming more likely?

Is a Reform-Tory pact becoming more likely?Today’s Big Question Nigel Farage’s party is ahead in the polls but still falls well short of a Commons majority, while Conservatives are still losing MPs to Reform

-

Taking the low road: why the SNP is still standing strong

Taking the low road: why the SNP is still standing strongTalking Point Party is on track for a fifth consecutive victory in May’s Holyrood election, despite controversies and plummeting support

-

What difference will the 'historic' UK-Germany treaty make?

What difference will the 'historic' UK-Germany treaty make?Today's Big Question Europe's two biggest economies sign first treaty since WWII, underscoring 'triangle alliance' with France amid growing Russian threat and US distance

-

Is the G7 still relevant?

Is the G7 still relevant?Talking Point Donald Trump's early departure cast a shadow over this week's meeting of the world's major democracies

-

Angela Rayner: Labour's next leader?

Angela Rayner: Labour's next leader?Today's Big Question A leaked memo has sparked speculation that the deputy PM is positioning herself as the left-of-centre alternative to Keir Starmer

-

Is Starmer's plan to send migrants overseas Rwanda 2.0?

Is Starmer's plan to send migrants overseas Rwanda 2.0?Today's Big Question Failed asylum seekers could be removed to Balkan nations under new government plans