Has British politics entered a post-scandal era?

Housing Secretary Robert Jenrick clinging on to job amid planning row

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Boris Johnson has thrown his support behind Robert Jenrick amid calls for the housing secretary to resign over his involvement in a “cash for favours” row.

The prime minister insists he continues to have “full confidence” in Jenrick, who is fighting for his job after newly released text messages and emails suggest he saved property developer and Tory donor Richard Desmond up to £50m by rushing through a planning application.

So just what does it take for a minister to resign in politics today?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Are politicians now slower to resign?

Recent years have seen a number of high-profile politicians clinging on to office after becoming embroiled in controversy.

Johnson leads the country despite a facing a series of high-profile scandals, from his careless comments about jailed British-Iranian aid worker Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, to claims that he ditched his security detail while serving as foreign secretary to attend an “exotic” party hosted by Russian-born media tycoon Evgeny Lebedev, as The Guardian reported last year.

The PM’s current cabinet has a fairly chequered record too. In 2017, Priti Patel refused to resign as Theresa May’s international development secretary after repeatedly failing to disclose multiple unofficial meetings with Israeli ministers, business people and lobbyists.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The now home secretary was ultimately forced to quit after it emerged that she had two further meetings with Israeli officials without UK government officials present or in the know.

But Patel has managed to hang on to her current role despite multiple bullying allegations, including reports in March that her former aide had received a £25,000 payout from the government after allegedly attempting suicide following “unprovoked aggression” by the Tory minister.

Dominic Cummings has been equally tenacious in retaining his place at Downing Street. Although not a politician, the senior advisor is a political appointment, yet Johnson has refused to sack his right-hand man despite Cummings being caught caught breaking coronavirus lockdown rules.

The phenomenon of seeming unbudgeable political figures is by no means limited to the Tory party.

In 2016, a motion of no confidence in Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn passed by 172-40. But Corbyn held on as the party’s chief, while being dogged by allegations of anti-Semitism, until the disastrous 2019 general election result eventually forced him out.

And Keith Vaz continued to serve as a Labour MP after reports emerged in 2016 that he had offered to buy cocaine for sex workers. Vaz finally stood down at the election last December after the Commons Standards Committee recommended that he be slapped with a six-month ban from Parliament over the scandal.

What about the exceptions?

Of course, some rows prove too damaging for even the most brazen political figures to survive.

Alun Cairns quit as Welsh secretary last November amid allegations that he lied about his knowledge of an aide’s alleged “sabotage” of a rape trial.

And Amber Rudd stepped down as home secretary in April 2018 over the Windrush scandal, after admitting that she had “inadvertently misled” MPs over deportation targets.

However, Rudd was soon back in government as work and pensions minister, before resigning again - alongside the PM’s brother, universities minister Jo Johnson - over the Tory leader’s controversial prorogation of Parliament and “purge” of party moderates.

But arguably the most famous resignation in recent history is that of Theresa May in July 2019, after failing three times to get her Brexit deal through Parliament.

What has changed in modern politics?

“It feels like ministers are allowed to get away with far more than they did even a few years ago, for example when immigration minister Mark Harper stood down in 2014 over the illegal status of his cleaner,” Anoosh Chakelian wrote in the New Statesman in 2017.

She suggested that one factor might be that then PM “May is so weak that she can only get away with the least politically-contentious sackings”.

But digging deeper, it appears that political resignations or sackings due to scandal have never been all that common, according to Chakelian.

She pointed to research by Liam McLoughlin, a PhD politics researcher at the University of Salford, which found that between 1945 and 1997, only 34% of all scandals resulted in a ministerial resignation.

“So it looks like errant ministers have generally been getting away with it for most of history,” Chakelian concluded.

What may have changed is the extent to which voters are aware of such scandals, Richard Skinner argued in Vox last year.

“There is more national attention to these scandals than there was a generation ago. Cable news and social media can make a juicy story the topic of national conversation within hours,” he wrote.

But “on the other hand, partisans are more reluctant than ever to accept a ‘loss’”, Skinner added.

This refusal to accept blame, at least in public, has been noted by a number of commentators.

“Credit is due to some, like Boris Johnson and David Davis, who have indeed resigned,” James Bartholomew wrote in January 2019 article for The Telegraph calling for May to resign as PM after her Brexit deal was voted down in the Commons.

“They have done the right thing. But others have dishonoured themselves. The resulting cabinet is both low on quality and deserving of little respect.”

-

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?Talking Point The Trump administration is applying the pressure, and with Latin America swinging to the right, Havana is becoming more ‘politically isolated’

-

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predators

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predatorsCartoons Artists take on the real victim, types of protection, and more

-

Palestine Action and the trouble with defining terrorism

Palestine Action and the trouble with defining terrorismIn the Spotlight The issues with proscribing the group ‘became apparent as soon as the police began putting it into practice’

-

How corrupt is the UK?

How corrupt is the UK?The Explainer Decline in standards ‘risks becoming a defining feature of our political culture’ as Britain falls to lowest ever score on global index

-

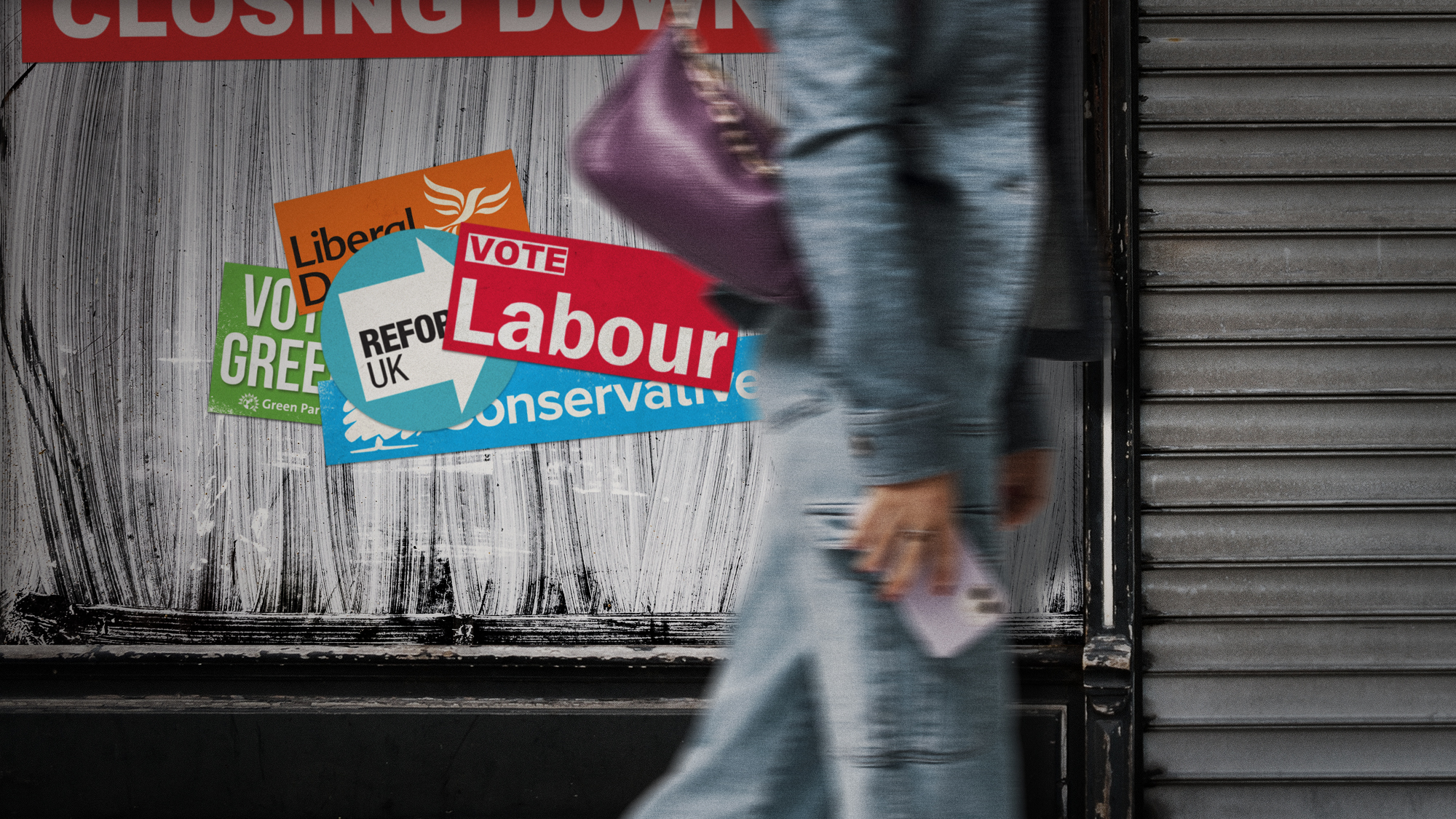

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?In the Spotlight Mass closure of shops and influx of organised crime are fuelling voter anger, and offer an opening for Reform UK

-

Biggest political break-ups and make-ups of 2025

Biggest political break-ups and make-ups of 2025The Explainer From Trump and Musk to the UK and the EU, Christmas wouldn’t be Christmas without a round-up of the year’s relationship drama

-

Is a Reform-Tory pact becoming more likely?

Is a Reform-Tory pact becoming more likely?Today’s Big Question Nigel Farage’s party is ahead in the polls but still falls well short of a Commons majority, while Conservatives are still losing MPs to Reform

-

The launch of Your Party: how it could work

The launch of Your Party: how it could workThe Explainer Despite landmark decisions made over the party’s makeup at their first conference, core frustrations are ‘likely to only intensify in the near-future’

-

Asylum hotels: everything you need to know

Asylum hotels: everything you need to knowThe Explainer Using hotels to house asylum seekers has proved extremely unpopular. Why, and what can the government do about it?

-

Taking the low road: why the SNP is still standing strong

Taking the low road: why the SNP is still standing strongTalking Point Party is on track for a fifth consecutive victory in May’s Holyrood election, despite controversies and plummeting support

-

Your Party: a Pythonesque shambles

Your Party: a Pythonesque shamblesTalking Point Comical disagreements within Jeremy Corbyn and Zarah Sultana's group highlight their precarious position