Coronavirus: does cold weather have an impact on Covid-19?

Experts says wintry conditions can affect both the spread of the virus and our ability to recover if infected

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

As Covid-19 spread through Europe last spring, there were hopes that warm summer temperatures would see off the virus - and fears about what winter might bring.

But in fact, the relationship between the weather and infection rates appears to be more complex: chilly Norway and Finland fared well in February, and Spain’s second wave took hold in August.

So what should we expect as the weather turns?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

A cold-loving virus

The bad news is that the Sars-CoV-2 virus that causes Covid seems to be better adapted to wintry conditions than we are.

“All viruses survive outside the body better when it is cold,” says the BBC. “The UK’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (Sage) says a temperature of 4C is a particular sweet spot for coronavirus.”

According to the Centre of Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM) at Oxford University, a 1C drop in temperature raises the R number - a measure of the spread of the epidemic - by about 0.04.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

So if an outbreak was stable at 27C, with ten infectious people infecting ten others, lowering the temperature to 5C would mean those ten people would infect about 20 more, and the epidemic would grow exponentially.

The virus is also hindered by humidity and UV light - both in short supply on winter days.

“When the weather turns cold, air gets drier,” says the medical news site STAT. “Turning on the heat dries both the air and the tissues lining the airways, impairing how well mucus removes debris and invaders like Sars-CoV-2.”

The human factor

Our own responses to cold weather also makes life easier for the virus. “We gather indoors once the weather turns and beer gardens and BBQs are less appealing,” says the BBC. “We also slam the windows shut so there is little ventilation.”

The human immune system performs less well during the winter too, which may mean people who catch Covid-19 get more seriously ill.

During the spring, scientists recorded “a roughly 15% drop in mortality for every one degree Celsius rise in temperature”, the Covid Symptom Study reports. But as temperatures drop this autumn, the trend may be reversed.

However, says the CEBM, “weather alone cannot explain the variability” in the spread or seriousness of the virus. “Confounding” factors such as social distancing and other public health measures may be far more significant.

Holden Frith is The Week’s digital director. He also makes regular appearances on “The Week Unwrapped”, speaking about subjects as diverse as vaccine development and bionic bomb-sniffing locusts. He joined The Week in 2013, spending five years editing the magazine’s website. Before that, he was deputy digital editor at The Sunday Times. He has also been TheTimes.co.uk’s technology editor and the launch editor of Wired magazine’s UK website. Holden has worked in journalism for nearly two decades, having started his professional career while completing an English literature degree at Cambridge University. He followed that with a master’s degree in journalism from Northwestern University in Chicago. A keen photographer, he also writes travel features whenever he gets the chance.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillance

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillanceUnder the radar The disease can spread through animals and humans

-

Covid-19 mRNA vaccines could help fight cancer

Covid-19 mRNA vaccines could help fight cancerUnder the radar They boost the immune system

-

The new Stratus Covid strain – and why it’s on the rise

The new Stratus Covid strain – and why it’s on the riseThe Explainer ‘No evidence’ new variant is more dangerous or that vaccines won’t work against it, say UK health experts

-

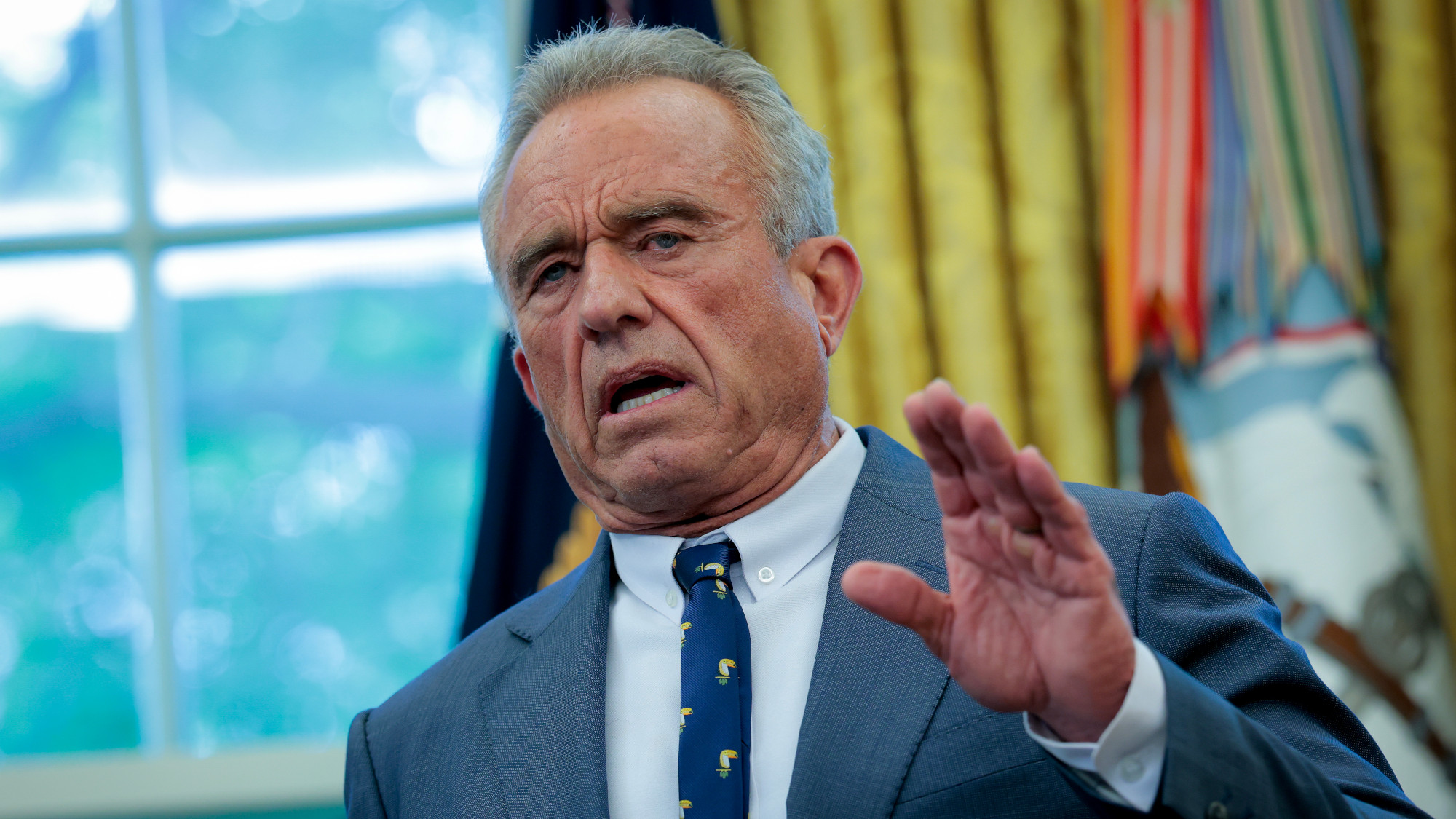

RFK Jr. vaccine panel advises restricting MMRV shot

RFK Jr. vaccine panel advises restricting MMRV shotSpeed Read The committee voted to restrict access to a childhood vaccine against chickenpox

-

RFK Jr. scraps Covid shots for pregnant women, kids

RFK Jr. scraps Covid shots for pregnant women, kidsSpeed Read The Health Secretary announced a policy change without informing CDC officials

-

New FDA chiefs limit Covid-19 shots to elderly, sick

New FDA chiefs limit Covid-19 shots to elderly, sickspeed read The FDA set stricter approval standards for booster shots

-

RFK Jr.: A new plan for sabotaging vaccines

RFK Jr.: A new plan for sabotaging vaccinesFeature The Health Secretary announced changes to vaccine testing and asks Americans to 'do your own research'

-

Five years on: How Covid changed everything

Five years on: How Covid changed everythingFeature We seem to have collectively forgotten Covid’s horrors, but they have completely reshaped politics