52 ideas that changed the world - 31. Prison

From the brutal conditions of medieval jails to the modern ‘rehabilitation not incarceration’ focus in Scandinavia

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In this series, The Week looks at the ideas and innovations that permanently changed the way we see the world. This week, the spotlight is on prison:

Prison in 60 seconds

Oscar Wilde first saw the inside of a prison 13 years before he wrote De Profundis, his famous 55,000-word letter to his lover, Lord Alfred Douglas, from his cell at Reading Gaol.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

On seeing the state of the inmates at a jail in Lincoln, Nebraska in 1882, Wilde wrote of being confronted with “poor odd types of humanity in striped dresses making bricks in the sun”. All of the faces “were mean-looking, which consoled me, for I should hate to see a criminal with a noble face”.

By the time of his own incarceration for indecency, Wilde’s views had softened on those residing in prison. Reviewing a book of poetry composed behind bars by the anti-imperialist Wilfred Blunt, Wilde wrote that “an unjust imprisonment for a noble cause strengthens as well as deepens the nature”.

Wilde’s changing attitude to the jail population reflected a shift in the general perception of criminality. The prisons of Wilde’s Britain were a far cry from the rehabilitation-focused penal systems of the 21st century.

Prisons, which are often run by governments, are usually secure facilities (though not always) that constrain the movements and social interactions of prisoners. The notion was born out of the barbaric origins of the medieval torture chamber, but by the eighteenth centry it had shifted towards imprisonment with labour, according to the Howard League for Penal Reform.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

This then changed again as prisons became more concerned with the concept of rehabilitation. This time prisons moved towards the “modern mechanisms of criminal justice”, what French philosopher Michael Foucault described as not a physical imprisonment, but “an economy of suspended rights” aimed at reshaping individual behaviour.

How did it develop?

The earliest descriptions of imprisonment corresponded closely with the spread of the written word and the formalisation of early legal codes. However, the earliest legal documents – for example the Babylonian Code of Hammurabi dating from about 1750 BC – focused on retribution from the victim, rather than state-led punishment as we now recognise it.

Plato began to develop ideas about rehabilitation and in Plato’s Laws considered the law’s role in making citizens “virtuous”. Plato dwelt on the suggestion that injustice is a disease of the soul that can be cured through punishment.

Plato’s Greece did have prisons – called desmoterion, meaning “place of chains” – however they were used more for the holding of prisoners who had been condemned to death. The Ancient Romans also used imprisonment for the same purpose, and in 640 BC, the Mamertine Prison, known as the Tullianum, was erected.

The 400-year-old San Giuseppe dei Falegnami Roman Catholic church now stands on the site of the prison, but at the time it would have been a squalid series of dungeons in the sewers under Rome.

During the Middle Ages, prison conditions did not improve. Across Europe, brutal punishment was still prescribed to rule-breakers, with “castles, fortresses and the basements of public buildings” given over to housing the incarcerated.

As historian Patricia Turning writes in Crime and Punishment in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Age, by the 13th century “the right to imprison criminals… gave a certain legitimacy to political administrations, from the king to regional counts to city councils”.

Up until the late 17th and early 18th century, justice mostly involved performative displays of violence against criminals. Public executions and torture were widespread, with the Bloody Code imposing the death penalty for hundreds of often petty offences in the United Kingdom.

In the 18th century, there was a shift away from public executions as public perceptions of violence began to shift. The Howard League notes that a more complex penal system developed during the period, including the widespread introduction of “houses of correction”. The first of these in the UK was Bridewell Prison - a complex in London that was originally built as Bridewell Palace, a residence for Henry VIII.

What precisely prisons were for during this time was divided between two philosophical outlooks. In From Newgate to Dannemora: The Rise of the Penitentiary in New York, David Lewis notes that Enlightenment ideas of utilitarianism and rationalism clashed, leading to discussion of whether prisons should be a deterrent or a site of “moral reform” (an early description of rehabilitation).

This divide was embodied by two prison reformers of the time: John Howard – after who the Howard League is named – and Jeremy Bentham. Bentham, a utilitarian, believed that the prisoner should suffer a severe regime, while Howard advocated for the rehabilitation of prisoners so that they could be reintroduced into society.

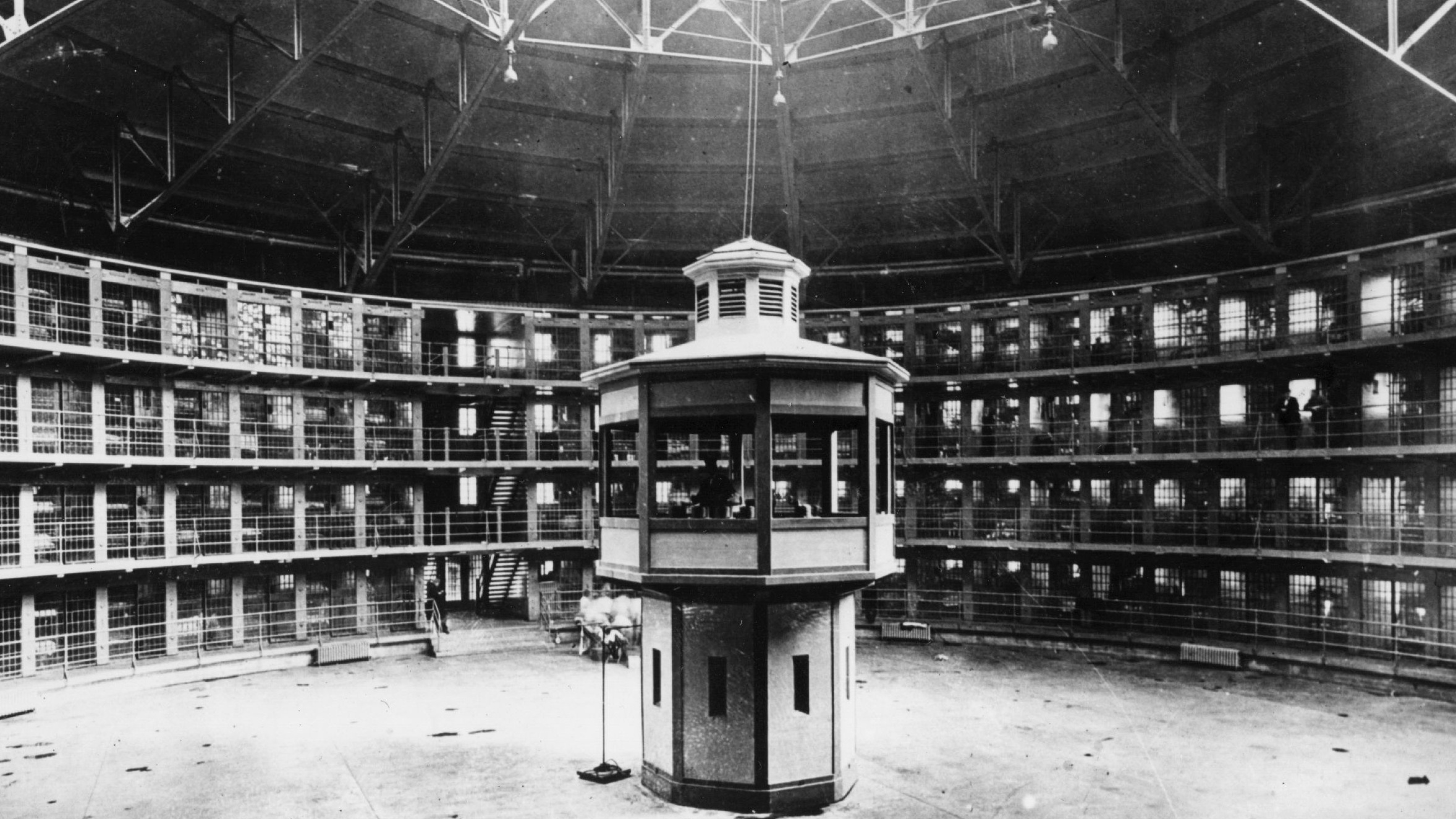

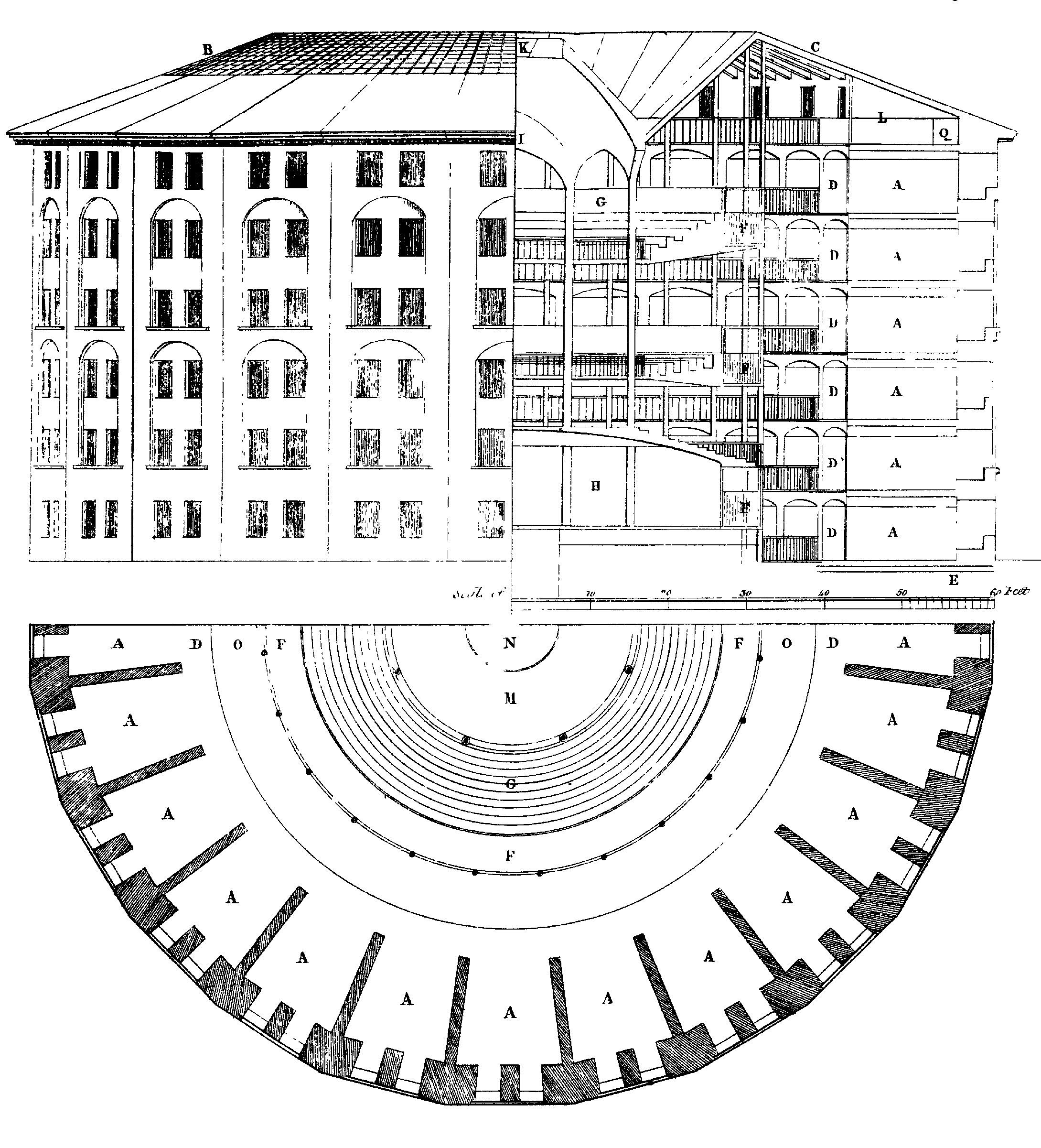

Bentham would go on to design “the panopticon” (pictured below), in which prisoners were under observation at all times. Over 200 years later, Foucault would use Bentham’s panopticon design as a metaphor for the “modern disciplinary society”, in which acts of violence had been replaced with efforts to reshape the behaviour of individuals.

The first state prison in England was the Millbank Prison, established in 1816 on the site of the current Tate Gallery in London, with a capacity for just under 1,000 inmates. In 1842, Pentonville Prison in London opened, kickstarting the trend for ever-increasing incarceration rates and the use of prison as the primary form of crime punishment.

In 1786 the state of Pennsylvania in the US passed a law which forced all convicts who had not been sentenced to death to be placed in penal servitude to do public works projects such as building roads, forts and mines. This inspired the rise of so-called “chain gangs”.

The notion of moral reformation took on a religious bent in Pennsylvania around this time. According to the 2004 book Voices from Prison on the life histories of black male prisoners in the US, 1790 saw the Walnut Street Jail in Pennsylvania begin locking its prisoners in solitary cells to reflect on their sins, accompanied by nothing but religious literature.

By the 1800s, prisons as a means of rehabilitation were becoming more mainstream, though the methods for reforming those behind bars were still harsh. Mary Bosworth writes in The U.S. Federal Prison System that the “Auburn system” developed in New York confined prisoners in separate cells and prohibited them from speaking.

First introduced at Auburn State Prison, the system was modelled on the strictness of a school classroom, where pupils would be shaped and moulded by their teachers. The method became famous and is mentioned by French diplomat Alexis de Tocqueville in his book Democracy in America, based on a visit to the US.

In the early 1900s, major reforms began in the UK’s prison system, spearheaded by the Liberal Home Secretary Winston Churchill, who had been imprisoned himself during the Boer War. He said: “I certainly hated my captivity more then I have ever hated any other period in my whole life... Looking back on those days I’ve always felt the keenest pity for prisoners and captives.”

His biographer, Paul Addison, would later add that “more than any other Home Secretary of the 20th century, Churchill was the prisoner’s friend”.

Churchill’s reforms - unpopular though they were at the time - aimed to make prison more bearable and more likely to rehabilitate prisoners. The policy left Britain with one of the most liberal prison systems in the Western world, but by the mid-20th century this had been far outstripped by the Scandinavian penal system.

Sweden was the first country to wholeheartedly embrace the idea of “rehabilitation not incarceration”. In 1965 it introduced a criminal code that emphasised punishments that reduced prison time. The hugely progressive move included a focus on conditional sentences, probation for first-time offenders and the more extensive use of fines.

This influenced a shift in imprisonment across Europe, with France and the Netherlands following Sweden’s example and experiencing a rapid fall in prison numbers as a result.

In 2014, Sweden was able to close four of its 56 prisons, as only 4,500 people out of a total population of 9.5 million were being held in jail. At the time, Swedish politician Nils Oberg told The Guardian that “prison is not for punishment in Sweden. We get people into better shape.”

The same year, Juliet Lyon, director of the Prison Reform Trust, said that the UK’s then Justice Secretary, Chris Grayling, was introducing measures that amounted to “a ramped-up political emphasis on punishment rather than real rehabilitation”.

The damming response suggested that despite Britain leading the world in liberalising prisons in the early 1900s, by the turn of the 21st century it had fallen behind. The number of deaths in the ten worst prisons in England and Wales are increasing year on year, with understaffing, drug use, crumbling infrastructure and overcrowding all playing a role.

How did it change the world?

More than 11 million people are currently held in prison around the world - ranging from incarceration in the liberal penal system of Scandinavia, to the hidden detention sites of China and North Korea from which many never return.

The concept of imprisoning people ushered in a type of justice that focused less on the violent retribution endorsed in Britain's Bloody Code and later allowed for rehabilitation to become a vital part of modern criminal justice systems.

Just as Oscar Wilde’s attitude to criminals tempered, so too has society’s, with polling in the US – which houses 22% of the world’s prison population – showing that 40% of people believe rehabilitation is the most important function of a prison system.

In the same poll, 53% supported the abolition of solitary confinement, a stark comparison to the uncompromising rules of the Auburn system or the authoritarianism of Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon.

Joe Evans is the world news editor at TheWeek.co.uk. He joined the team in 2019 and held roles including deputy news editor and acting news editor before moving into his current position in early 2021. He is a regular panellist on The Week Unwrapped podcast, discussing politics and foreign affairs.

Before joining The Week, he worked as a freelance journalist covering the UK and Ireland for German newspapers and magazines. A series of features on Brexit and the Irish border got him nominated for the Hostwriter Prize in 2019. Prior to settling down in London, he lived and worked in Cambodia, where he ran communications for a non-governmental organisation and worked as a journalist covering Southeast Asia. He has a master’s degree in journalism from City, University of London, and before that studied English Literature at the University of Manchester.