What does impeachment mean and how does it work?

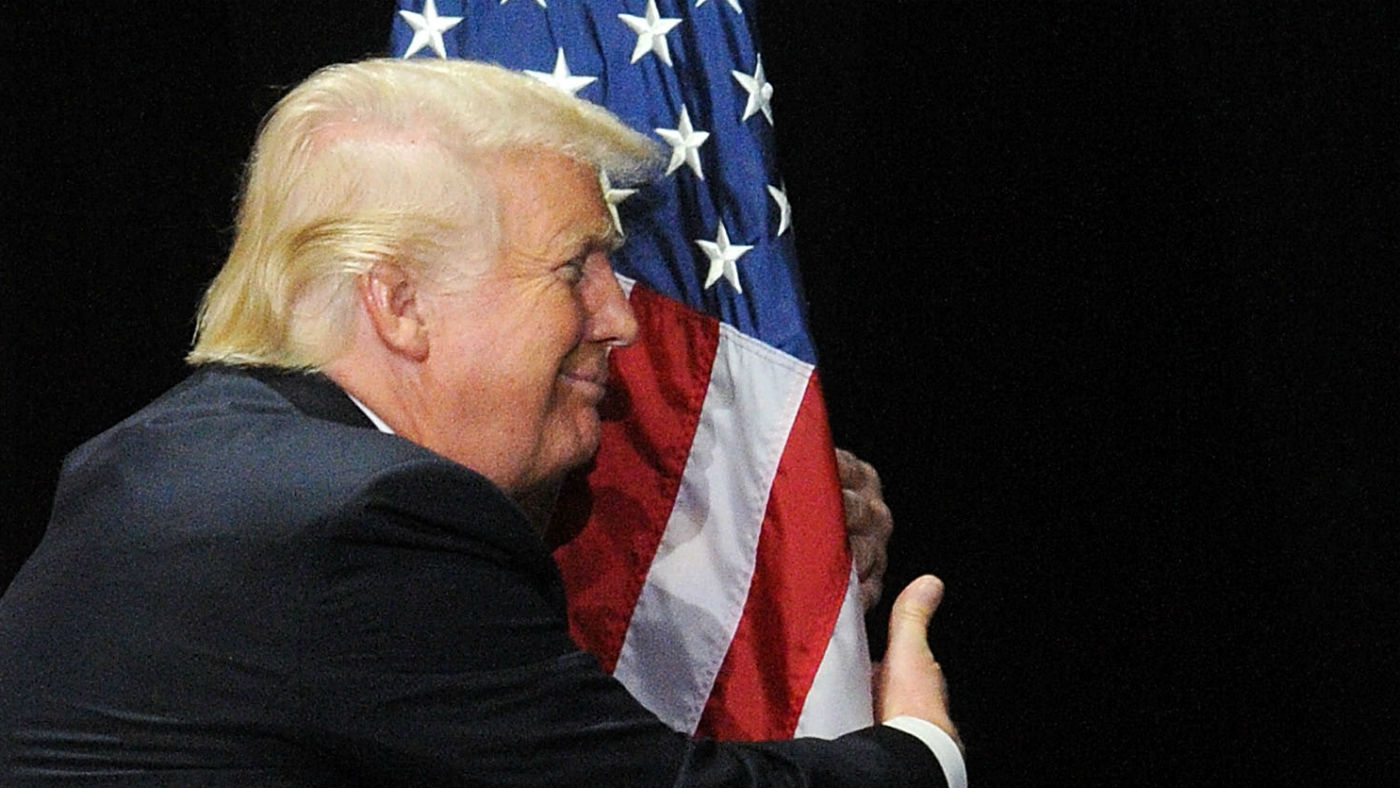

Televised hearings on the Donald Trump investigation begin today

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The US House of Representatives is convening today for the first public impeachment hearings in 20 years.

The House Intelligence Committee will hear allegations of misconduct against President Donald Trump in a process that could potentially result in his removal from office.

Trump had “struggled furiously” to prevent the impeachment proceedings reaching this stage, “blocking witnesses, attacking investigators and throwing up a social media smokescreen”, says The Guardian.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

“It is a very momentous occasion,” says Richard Briffault, an impeachment expert and professor at New York City’s Columbia Law School. “This will only be the fourth time in more than 225 years that Congress has considered the impeachment of a president.”

But how exactly does impeachment work – and how has it been used in the past?

What is impeachment?

Under US law, any federal official suspected of serious wrongdoings can be charged and tried, a process known as impeachment.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In a process comparable to indictment and trial in a standard criminal court, the House of Representatives deliberates on the charges and votes on whether the case should proceed. The upper chamber, the Senate, is in charge of conducting any such trial.

The impeachment of a president is presided over by the chief justice of the Supreme Court, while the vice president presides in cases concerning other federal officials.

The term refers only to the act of charging someone with an “impeachable” offence, not to the outcome of the investigation, so an official can be impeached whether or not they are found guilty.

“Impeachment is actually a legacy of British constitutional history,” reports the New Statesman, although the process in the UK is now considered obsolete.

What offences are impeachable?

“The president, vice president and all civil officers of the United States, shall be removed from office on impeachment for, and conviction of, treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanours,” says Section Four of Article Two of the US Constitution.

While the first two instances are self-explanatory, “high crimes and misdemeanours” can be used to cover a wide range of offences which fall under the umbrella of misconduct relating to a position of public responsibility, including perjury, dereliction of duty and misuse of assets.

Trump is accused of “betraying his oath of office and the nation’s security by seeking to enlist a foreign power to tarnish a rival for his own political gain”, says The New York Times.

If true, this would be considered a violation of the US Constitution and an illegal act.

Has a president ever been impeached?

Two US presidents have been impeached, although neither was actually convicted or forcibly removed from office.

Andrew Johnson won the dubious honour of becoming the first president to be impeached in 1868, after he was accused of bypassing federal law to replace the secretary of war without the Senate’s approval. A single vote saved him from the two-thirds Senate majority needed to convict and he continued to serve until the end of his term later that year.

Bill Clinton’s 1999 impeachment hearings became appointment viewing for TV audiences in the US and around the world, as he appeared before the Senate accused of lying under oath about his extra-marital affair with White House intern Monica Lewinsky. Like Johnson, Clinton was ultimately acquitted and served out the remainder of his term in office.

In the aftermath of the Watergate scandal, the House of Representatives prepared to impeach then-president Richard Nixon, but “Tricky Dicky” resigned before a vote could be taken to begin proceedings, avoiding near-certain conviction.

What has happened so far in the Trump investigation?

The proceedings began after Trump was accused of coercing Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky by threatening during a July phone call to withhold military aid unless he investigated the US leader’s political rival Joe Biden.

In August, a US intelligence whistle-blower filed a complaint to the Inspector General of the Intelligence Community, Michael Atkinson, who passed on the matter of “urgent concern” to the chair of the House Intelligence Committee, Adam Schiff.

On 24 September, the formal impeachment inquiry was announced by Democratic Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi. The following day, Trump released a copy of the notes that US officials had taken on the 25 July call at the centre of the row. The transcripts didn’t prove his guilt but were later found to have crucial omissions.

The following month, the US ambassador to Ukraine claimed he had been told by the US ambassador to the EU and others that aid to Ukraine was contingent on Zelensky publicly declaring an investigation into Biden.

On 31 October, the House of Representatives voted to formalise the process for the public impeachment hearings, by 232-196.

The US ambassadors to the EU and Ukraine have said publicly that they were aware of a quid pro quo from Trump to Zelensky.

-

The environmental cost of GLP-1s

The environmental cost of GLP-1sThe explainer Producing the drugs is a dirty process

-

Greenland’s capital becomes ground zero for the country’s diplomatic straits

Greenland’s capital becomes ground zero for the country’s diplomatic straitsIN THE SPOTLIGHT A flurry of new consular activity in Nuuk shows how important Greenland has become to Europeans’ anxiety about American imperialism

-

‘This is something that happens all too often’

‘This is something that happens all too often’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffs

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffsSpeed Read Six Republicans joined with Democrats to repeal the president’s tariffs

-

Bondi, Democrats clash over Epstein in hearing

Bondi, Democrats clash over Epstein in hearingSpeed Read Attorney General Pam Bondi ignored survivors of convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein and demanded that Democrats apologize to Trump

-

How corrupt is the UK?

How corrupt is the UK?The Explainer Decline in standards ‘risks becoming a defining feature of our political culture’ as Britain falls to lowest ever score on global index

-

US to send 200 troops to Nigeria to train army

US to send 200 troops to Nigeria to train armySpeed Read Trump has accused the West African government of failing to protect Christians from terrorist attacks

-

Grand jury rejects charging 6 Democrats for ‘orders’ video

Grand jury rejects charging 6 Democrats for ‘orders’ videoSpeed Read The jury refused to indict Democratic lawmakers for a video in which they urged military members to resist illegal orders

-

Trump links funding to name on Penn Station

Trump links funding to name on Penn StationSpeed Read Trump “can restart the funding with a snap of his fingers,” a Schumer insider said

-

Trump reclassifies 50,000 federal jobs to ease firings

Trump reclassifies 50,000 federal jobs to ease firingsSpeed Read The rule strips longstanding job protections from federal workers

-

Is the Gaza peace plan destined to fail?

Is the Gaza peace plan destined to fail?Today’s Big Question Since the ceasefire agreement in October, the situation in Gaza is still ‘precarious’, with the path to peace facing ‘many obstacles’