Cancer ‘vaccine’ to enter human trials

Single injection caused immune system to obliterate tumours in trials on mice

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

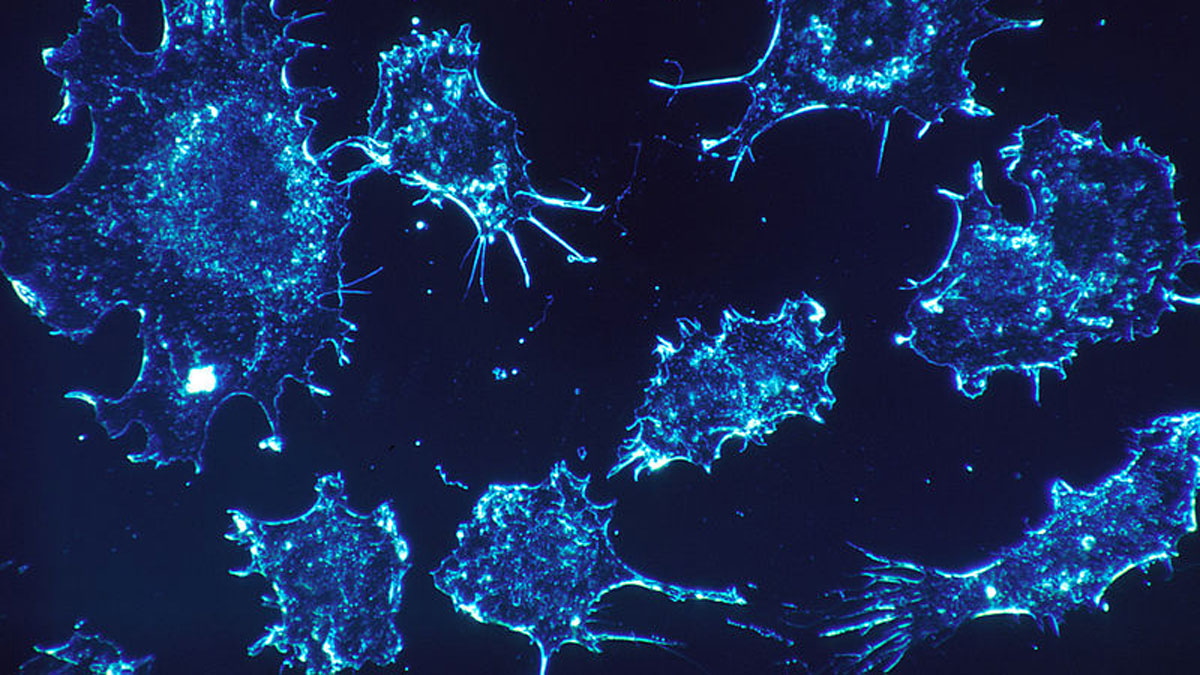

A revolutionary cancer vaccine that can eliminate tumours even after they have spread throughout the body is to go into human trials.

The move follows trials on mice in which the treatment worked “startlingly well”, according to researchers, with 90% of the animals cured after one injection, and the rest after a second jab.

The team at Stanford University, in California, say that “injecting tiny amounts of two drugs directly into a tumour not only kills the original cancer, but also triggers an ‘amazing bodywide’ reaction which destroys distant cancer cells”, reports The Daily Telegraph.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The drug combination works by “switching on immune cells inside the tumours which have been deactivated by the cancer, then boosting them so they can go to work killing the disease”, the newspaper adds.

“When we use these two agents together, we see the elimination of tumours all over the body,” said Professor Ronald Levy, who led the study.

“This approach bypasses the need to identify tumour-specific immune targets and doesn’t require wholesale activation of the immune system or customisation of a patient’s immune cells.”

For the human trial, “Levy plans to recruit 15 patients with low-grade lymphoma”, says the Daily Mail. “If successful, Levy believes the treatment could be useful for many tumour types.”

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In the future, he believes oncologists “could inject both [agents] into solid tumours in humans before surgery as a way to prevent recurrence from stray tumours that spread but weren’t detected”, according to the newpaper.

“I don’t think there’s a limit to the type of tumour we could potentially treat, as long as it has been infiltrated by the immune system,” Levy said.

Levy and his team “deserve a lot of credit” for testing the combined treatment on a strain of mouse that is prone to spontaneously develop breast tumours - which mimics how cancer arises in humans, immunologist Drew Pardoll, of the Bloomberg-Kimmel Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy in Baltimore, Maryland, told Science magazine.

But “the big question is whether the approach works in people, as most rodent cancer therapies don’t translate to humans”, the magazine notes.

-

The mystery of flight MH370

The mystery of flight MH370The Explainer In 2014, the passenger plane vanished without trace. Twelve years on, a new operation is under way to find the wreckage of the doomed airliner

-

5 royally funny cartoons about the former prince Andrew’s arrest

5 royally funny cartoons about the former prince Andrew’s arrestCartoons Artists take on falling from grace, kingly manners, and more

-

The identical twins derailing a French murder trial

The identical twins derailing a French murder trialUnder The Radar Police are unable to tell which suspect’s DNA is on the weapon

-

Home Office worker accused of spiking mistress’s drink with abortion drug

Home Office worker accused of spiking mistress’s drink with abortion drugSpeed Read Darren Burke had failed to convince his girlfriend to terminate pregnancy

-

In hock to Moscow: exploring Germany’s woeful energy policy

In hock to Moscow: exploring Germany’s woeful energy policySpeed Read Don’t expect Berlin to wean itself off Russian gas any time soon

-

Were Covid restrictions dropped too soon?

Were Covid restrictions dropped too soon?Speed Read ‘Living with Covid’ is already proving problematic – just look at the travel chaos this week

-

Inclusive Britain: a new strategy for tackling racism in the UK

Inclusive Britain: a new strategy for tackling racism in the UKSpeed Read Government has revealed action plan setting out 74 steps that ministers will take

-

Sandy Hook families vs. Remington: a small victory over the gunmakers

Sandy Hook families vs. Remington: a small victory over the gunmakersSpeed Read Last week the families settled a lawsuit for $73m against the manufacturer

-

Farmers vs. walkers: the battle over ‘Britain’s green and pleasant land’

Farmers vs. walkers: the battle over ‘Britain’s green and pleasant land’Speed Read Updated Countryside Code tells farmers: ‘be nice, say hello, share the space’

-

Motherhood: why are we putting it off?

Motherhood: why are we putting it off?Speed Read Stats show around 50% of women in England and Wales now don’t have children by 30

-

Anti-Semitism in America: a case of double standards?

Anti-Semitism in America: a case of double standards?Speed Read Officials were strikingly reluctant to link Texas synagogue attack to anti-Semitism