How foreign aid screwed up Liberia's ability to fight Ebola

Foreign aid has created a hopelessly dependent political class that stays in business by ignoring good governance and begging its Western benefactors instead

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

President Obama is sending military personnel and $750 million to Liberia and other Ebola-afflicted countries in West Africa. At this point, such aid might offer the only hope of containing this deadly epidemic — but foreign aid also had a big hand in creating Africa's Ebola problem in the first place.

How? By breeding a dependence mentality that has prevented these counties from generating their internal institutional defenses to deal with public health emergencies.

Nothing illustrates this better than the contrasting courses of the disease in Liberia, one of the most heavily indebted countries on the continent, and Nigeria, one of the least.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Global aid agencies have berated America and other Western countries for their plodding response and letting Ebola's hemorrhagic virus infect about 10,000 people in Liberia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone, killing roughly half of them. But the reality is that distant powers, no matter how well intentioned, have never been any good at proactively identifying and responding to such emergencies, precisely because they are distant. Hence, they have to rely on intermediary groups such as the World Health Organization, which happens to have an unbroken record of botching every response to every recent epidemic, from bird flu to cholera. But even if the WHO were less dysfunctional, it is far from clear that it could orchestrate a global response that could effectively replace strong leadership by local authorities. And local government rarely develops strong institutional abilities and leadership if it is too dependent for too long on foreign aid.

Ebola is an awful disease. But it is not as contagious as, say, influenza. The only way of getting it is through close contact with the bodily fluids of an infected person. Preventing its spread requires not sophisticated equipment or know-how that developing countries don't have — but quick and aggressive steps to isolate, track, and monitor patients, all of which is common knowledge in African public health circles.

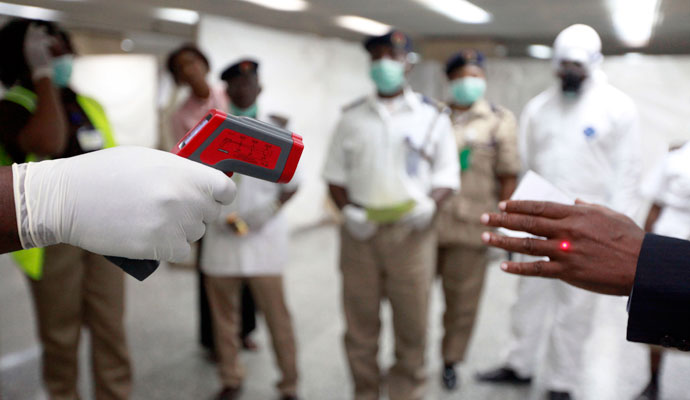

This is precisely what Nigerian authorities did when an infected Liberian-American man collapsed in Lagos airport. They quickly isolated him once his condition was diagnosed. They also mounted an immediate campaign to track down and monitor about 900 people who came in contact with him. They tapped staff from the country's polio-eradication program to help run an emergency operations center. Ultimately, despite its dense population, Nigeria kept its outbreak to a grand total of 19 cases with only seven casualties — a mortality rate of 37 percent.

Liberia, however, is another story.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Unlike Nigeria, Liberia's immediate reaction was not to marshal its domestic resources but to hold press conferences and appeal for international aid, points out Johannesburg-based Yale World Fellow Sisonke Msimang. Liberian President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, a Nobel peace laureate, even penned an open letter to the "world" this week, plaintively crying that Ebola wasn't a domestic problem but a global one that "governments to international organizations, financial institutions to NGOs, politicians to ordinary people in the street in every corner of the world" had a "duty" to combat through "emergency funds, medical supplies, or clinical capacity."

But the "world" has been supplying all of this and more to Liberia in spades, observes Msimang. Indeed, Liberia is among the largest aid recipients on the continent, with about 75 percent of its budget supplied by aid agencies. It receives $139 per capita in loans and grants, according to World Bank figures, compared with Nigeria's $11 per capita.

Liberia's capital, Monrovia, where 305 new Ebola cases were reported last week alone, is practically crawling with NGOs and aid workers. More stunningly, the U.N. is already spending $500 million to maintain a peacekeeping force. "The virus has managed to escape from a country that has one of the largest concentration of 'helpers' in the world," Msimang writes.

This might seem surprising, but it is actually perfectly predictable. Western aid, though aimed at helping Liberia recover from decades of brutal civil wars, has created a hopelessly dependent political class that stays in business by ignoring good governance and appealing to its Western benefactors.

Liberian authorities therefore have neither the wherewithal nor the trust of their citizens to mobilize an action plan. In fact, Monrovians in a slum initially attacked crisis responders who approached them about the disease because they believed that Ebola was a government ploy to shake down international agencies for more aid. Efforts to cordon off affected slums have resulted in deadly clashes with authorities by locals who fear that far from helping them, the government will consign them to certain death. "They were saying, in no uncertain terms, that the hand that feeds them is also the hand that pinches them," notes Msimang.

So what should America and the West do?

For the moment, they have no choice but to put in place the infrastructure that Liberia's predatory rulers have neglected. This means erecting treatment centers, training health-care workers, and handing out protective gear.

But once the disease is under control, America should leave quickly and start weaning Liberia off its teat. Like Ebola, excessive aid corrodes the body politic from the inside by breeding unaccountable rulers and undermining governance.

Nigeria is better off because it stands on its own two feet. America will do Liberia a favor by allowing it to do the same.

Shikha Dalmia is a visiting fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University studying the rise of populist authoritarianism. She is a Bloomberg View contributor and a columnist at the Washington Examiner, and she also writes regularly for The New York Times, USA Today, The Wall Street Journal, and numerous other publications. She considers herself to be a progressive libertarian and an agnostic with Buddhist longings and a Sufi soul.